The new tea party

Updated: 2013-07-29 11:22

By Pauline D. Loh (China Daily)

|

||||||||

|

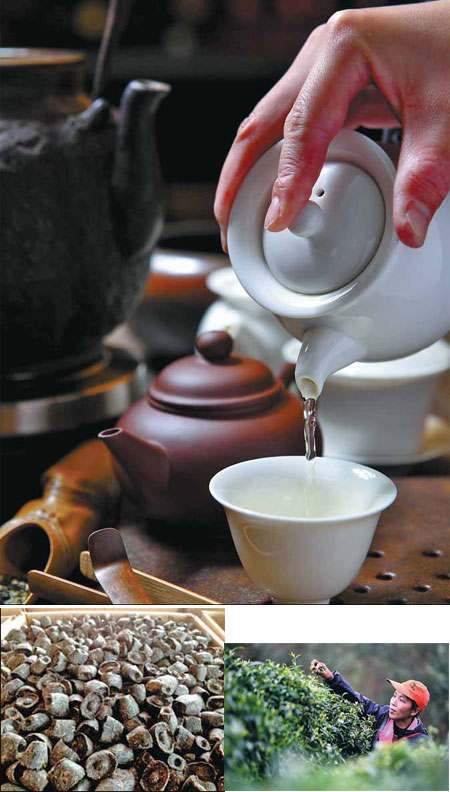

Left: Loose tea leaves are pressed into ingot-shaped bricks. They were traditionally carried on the backs of horses to Tibet on the chama gudao, the ancient Tea and Horse Caravan Route. Right: Tea farmers in the Guangxi Zhuang autonomous region are busy picking spring tea in the fields. Pailine D. Loh / China Daily, huang Xuhu / for China Daily |

|

Cakes of pu'er tea are collector's items, carefully kept and aged like fine wines. |

Tea is not just a drink. It is an integral part of the cultural and historical heritage of China. And, like all aspects of culture, it is always evolving. Pauline D. Loh tracks the trends from Kunming, Yunnan, and Beijing that indicate tea culture is undergoing significant changes.

Tea, like wines, mellow as they age, developing smoothness and subtlety in taste that is lacking in brash new brews. Similarly, Chinese tea culture traces its roots back to Lu Yu (AD 733-804), the patron saint who elevated tea drinking to an art about 1,300 years ago.

In the current economic climate, tea in China is enjoying a renaissance of awareness and appreciation that crosses psychographic and demographic barriers, with tendrils of influence reaching far across the seas.

Tea culture has always reveled in the attention of the upper classes whenever the country is settled and prosperous.

It used to be the drink that lubricated gentle prose and poetry from scholars of classic literature. It was the drink of the gentry and equally the drink of the agrarian poor, whose daily solace after a hard day's work in the fields would be a pot of hot water flavored by a few precious leaves.

It's no different now, although rare are the rough brews thrown together in large copper pots meant only to quench the thirst of the sweaty manual class.

Instead, there is a whole new order, where leaves are carefully classified according to taste, terroir and the ting-a-ling of cash registers and whole new support industries are flourishing alongside catering to the new tea connoisseurs.

New kilns and old kilns are producing tea wares that range from rustic ceramics to delicate porcelains. There are tea pots of every size and shape, cups as delicate as eggshells, tiny jugs that allow the brew to breathe before being poured into cups, holders that support tea colanders, ewers that hold tea cups between brews, tea urns that store the leaves

Then there are the tea slabs and tables made from blocks of sculpted tree roots and slabs of black stone and marble.

For a price, tea connoisseurs can enjoy their tea-making with the full paraphernalia, although tags are seldom fewer than four figures and the zeroes may stretch to hundreds of thousands of yuan for the true collectors.

Tea is big business. And the collectors and connoisseurs are willing to pay.

In Kunming, the capital of Southwest China's Yunnan province, specialist shops display tea tables created from ancient tree roots, mostly imported from Myanmar. The tabletops are smoothed and carved, and matching stools make it a set. The going price for a good set is no less than 10,000 yuan ($1,629), and the better woods can cost up to 100,000 yuan.

Tea slabs sculpted from a single block of black stone start from 5,000 yuan upward.

In Kunming, too, the tea merchants are laughing all the way to the bank, especially those who have had the foresight to bank up on stocks of pu'er tea.

Orders are pouring in all over the country and from abroad.

Even outside China, specialist teashops are mushrooming all over the United States, Europe, Australia and even Africa.

They sell loose-leaf teas in boutiques that are educating the world on how to appreciate teas like Dragon Well tea plucked before the spring rains, monkey-harvested silver needles, peony-scented white teas and the furry buds of the gigantic ancient pu'er tea trees from southern Yunnan.

Cheng Yu, a middle-aged wholesale tea merchant in Kunming, is a major supplier to these teashops. His family's Jiuwan Tea has its own factory and tea plantations, and Cheng is a one-man reference library on all things tea.

In fact, he is so respected that he is quoted often in the locally published Encyclopedia of Yunnan Tea, where his family business has an entire chapter to itself.

Ed Grumbine, 56, a research scholar with the Chinese Academy of Sciences at the Kunming Institute of Botany, was drinking black tea from China back in the United States long before he arrived to work here.

As soon as he had settled in Kunming, he started exploring the city's famous wholesale tea markets, which are more like tea towns. He soon found a tutor in Cheng Yu.

Grumbine took us to visit Cheng recently, and it proved an extremely educational experience.

There was a huge motorcycle outside Cheng's shop, a 1,800-cu-cm monster with upholstery that looked as if it was hijacked from a car. Images of Jack Kerouac on the road in designer jeans refuse to fade.

Indeed, when we meet Cheng, he looks more like a Beat Generation poet than a tea merchant, with long wavy locks and an easy confidence culled from a lifetime in the business. And he is wearing designer jeans.

We are invited to join him for tea at the table that is a fixture in every tea merchant's shop in Yunnan, with its supply of water at hand and a kettle almost constantly on the boil. The pu'er Cheng was drinking was very mellow - its natural tannins so tempered by age that it slid smoothly down the throat like the finest silk.

As we settle, he cues the two young ladies brewing tea to make a new pot. This time, the fragrance wafts up as soon as the hot water hits the leaves, and the room is scented with the unmistakable bouquet of jonquils, daffodils, narcissus - whatever you called the flower.

"This is a tea that has been recently developed," Cheng says, adding that it first came out around 2005.

It's a very floral black tea named zhongguohong, or China Red, linking it to a much older sister, the traditional dianhong cha, or Yunnan Red.

It is a tea very much in demand, but the harvest is small, and Cheng is reluctant to part with too much. The asking price here is 400 yuan per 100 grams, but by the time it is retailed abroad, the price may be $400. Even in Beijing, where small amounts are sold in the tea distribution center of Maliandao, the cost will be double what it is in Kunming.

This is a fair indication of how tea-buying habits are changing.

The most expensive teas are now finding a market, and so Qimen red tea is no longer exclusively for the Queen's afternoon cuppa, for example, but is offered in the specialist tea bars of international hotel chains all over the world.

There are some teas that can be drunk young, such as green teas or the jasmine teas so popular in the hutong courtyards of Beijing.

Tea is generally divided into black, red and green. The categories refer more to their processing rather than their color. The varieties are vast, and, like wine, different terroir also produce different tastes, aromas and colors.

There is a quiet revolution going on now that involves not only Chinese tea drinkers but also those abroad.

More Westerners are getting in on the act and developing a sophisticated taste for tea - without sugar or milk, if you please.

Contact the writer at paulined@chinadaily.com.cn.

(China Daily USA 07/29/2013 page8)

Most Viewed

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|

Today's Top News

Experts advise CEOs on how to make it in the US

Israeli-Palestinian peace talks to resume

Latest US-China talks should smooth the way

Audit targets local government debt

30 people killed in Italy coach accident

Brain drain may be world's worst

Industry cuts cloth to measure up to buyers' needs

Reckless projects undermine the prosperity hopes

US Weekly

|

|