Art runs in his blood

Updated: 2013-09-25 07:22

By Han Bingbin (China Daily)

|

||||||||

Limelight | Tim Yip

Renowned costume designer and art director Tim Yip was once so disillusioned that he wanted a career change. Fortunately, the talented artist persevered and lived to tell his tale. Han Bingbin reports.

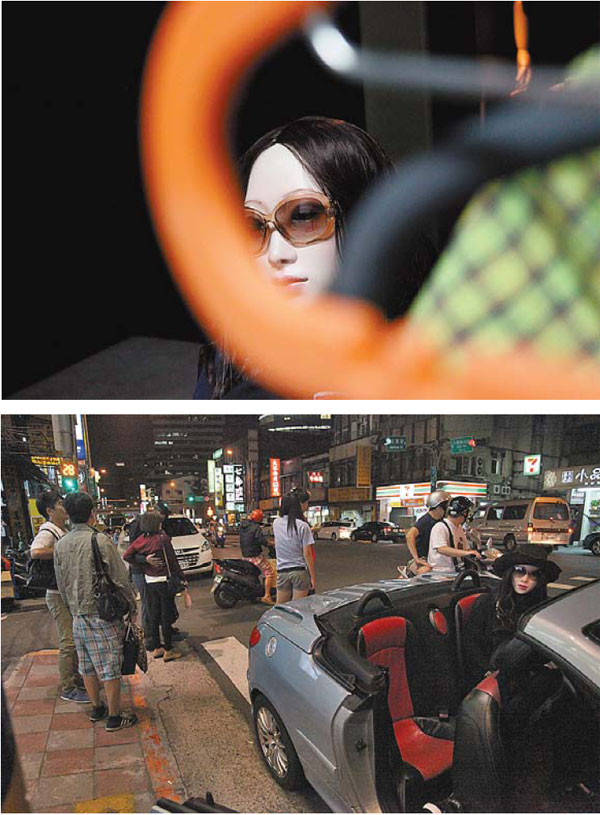

Tim Yip's unspeaking Muse and companion is a phantasmagoric girl of 17. Across Taipei, Beijing and Shanghai, he has placed her behind the wheel of a car, eating in a night market or drinking in a crowded bar. She dresses with style, but looks unassuming and reveals no clues of exceptional identity. Her name is Lili, a doll. As he does with film stars, renowned costume designer and art director Yip draws on her familiar face - a face that people feel comfortable with and grow fond of.

In 2008, Yip was invited by Today Museum to dabble in modern arts. Lili was one of the first three sculptures that Yip used to experiment with the musicality of human bodies, with which he became obsessed as a fan of European classical sculptures.

|

Above: Two photos taken by Tim Yip feature his model, Lili, a doll. Photos Provided to China Daily |

She started off as a hairless and naked doll with a pensive demeanor. Without serious planning, Yip started taking her to different places, putting her in various situations while dressing her differently, and then taking hundreds of photos. Through an exhibition at Beijing's Three Shadows Gallery, Yip believes Lili's inspiring ordinariness will remind viewers of just anyone they want her to be.

"When you stare at her for more than one minute, the communication starts. She will allow you to recall many things," Yip says.

In the curator Mark Holborn's words, we may find some element of erotic history in her gaze, just as we may find some sense of loss or of the passage of time as we catch a glance of her.

"This work can all of a sudden reveal a man's complication, so it's very powerful," Yip says.

Having been absent from his resounding art directing business for some years, Yip however is by no means off his track. Calling himself more a photographer than an art director, Yip started taking photos of film stars when he was still a photography student at the Hong Kong Polytechnic University.

Painting is another of his fortes. In the late 1980s, his winning pieces at a painting contest drew the attention of film director Tsui Hark. He was chosen as the art director for A Better Tomorrow III (1989) and helped make the trench coat-wrapped romantic gunfighter one of Chow Yun-fat's most classic and adorable screen images ever.

From there, he drove his career smoothly on track with his name appearing in prominent productions such as Stanley Kwan's Rouge (1988) and Full Moon in New York (1989). He also went to Taiwan, which he calls the turning point in his life, to formally experiment with traditional Chinese culture by working with avant-garde stage artists like Lin Hwai-min and his Cloud Gate Dance Theater.

In Taiwan, he embraced his first major award for art design at the Golden Horse Film Awards for creatively and bravely shaving off Joan Chen's hair and eyebrows in Clara Law's controversial Temptation of A Monk (1993).

Even after accumulating much prestige in the literary film genre, he remained a poor artist so confused about his future that he reportedly even asked Tsui Hark once to help him with a career change. So, when Ang Lee asked him to participate in Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon (2000), followed closely by an Oscar, Yip was pleasantly surprised and described the experience simply "super cool".

Yip soon shifted his focus to the Chinese mainland to work with big names such as Feng Xiaogang and John Woo in big budget costume movies like The Banquet (2006) and Red Cliff (2008).

Yip also worked as both a costume designer and art director with director Li Shaohong on three highly influential costume TV dramas. Through them, Yip was established in the heart of millions as "the master of ancient costume design" with his so-called New Orientalism aesthetics.

Now Yip's studio in the suburbs of Beijing, in curator Mark Holborn's words, is a creative laboratory and comfort zone where the artist is embedded in elements, ranging from Tang Dynasty (AD 618-907) interiors to men's hats in Shanghai 1920s, which drive his productive forces.

But inside his office, Yip is surrounded by, on the couch and next to his desk, the varied figures of his silent companion, Lili - a presence that Holborn sees as a sign of the loneliness of his working life in Beijing.

"To make his work he knows he has to give up a part of himself, especially in the service of the collective act of filmmaking. Lili was to some extent the product of a need to reclaim what was his. She belongs resolutely in his world," he says.

There are constant reports of Yip's admirable stubbornness. For example, during the shooting of Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon he firmly insisted on having a window reasonably shut in the sandy weather of Beijing, while the action directors and photographers both wanted it open because a character had to fly in through it.

In such cases, Yip is lucky to have directors who follow his advice, which is not usually the case in most teamwork. Besides, it's not just the conflicts with the directors. His unconventional costume design for Li Shaohong's remake A Dream of the Red Mansions (2010), though it was done carefully with much research, made him a target of criticism.

"People see you in an orthodox way. They see your interesting character not for what it really is. Even if they sometimes like it, they don't understand you," Yip says.

That's why he never gives up photography and other forms of pure arts. Even though they may cater to a smaller audience, they are to him more thorough and freer ways of self-expression.

In the pursuit of self-expression, he now has traveled even farther. The visual artist, who once said he never believed in words, has decided to write about one subject that he can express himself to the fullest capacity - philosophy.

The Connections, the second of his book trilogy released in August, explores the meaning of traditional Chinese aesthetics and the influence from its Western counterparts.

"When I start doing these (modern arts and writing books), I feel people truly beginning to like me, people whom I can truly communicate with. I don't want commercial factors to get in between me and my audiences. I want to gradually find myself," he says.

Contact the writer at hanbingbin@chinadaily.com.cn.

(China Daily USA 09/25/2013 page13)

World leaders at UN General Assembly

World leaders at UN General Assembly In photos: Deadly earthquake in Pakistan

In photos: Deadly earthquake in Pakistan

China to inaugurate Shanghai FTZ on Sept 29

China to inaugurate Shanghai FTZ on Sept 29

China's investment a 'job-saver' in Europe

China's investment a 'job-saver' in Europe

Pollution control plan to slash PM2.5

Pollution control plan to slash PM2.5

The beauty and beasts of selling hot houses

The beauty and beasts of selling hot houses

Tian'anmen's flowery moments for National Day

Tian'anmen's flowery moments for National Day

When animals meet beer

When animals meet beer

Most Viewed

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|

Today's Top News

208 killed as quake hits SW Pakistan

Foreign Minister Wang makes the rounds at UN

China to surpass US as top trader

Smithfield voters approve deal

Trending news across China

Ultra wealthy population shrinks in China: report

White House to enroll millions in Obamacare

Brazilian president blasts US for spying

US Weekly

|

|