Equity release plans aid aging society

Updated: 2013-10-14 06:56

By Grayson Clarke and Matthias Stepan (China Daily)

|

||||||||

The Chinese Dream has become a buzzword in Chinese and international media. While there are various interpretations about the origins and exact meaning of the Chinese Dream, it is quite obvious from the billboards and the articles that it mainly addresses the aspirations of the young. But if the younger generation are to realize their dreams, China has to overcome the problems posed by being the fastest aging society in history. An aging society offsets the demographic dividends, (potentially) burdens the public budgets and makes elderly care a big socioeconomic challenge.

The population of senior citizens in China is projected to increase from 194 million at the end of last year to 243 million by 2020 - and by 2050 China's elderly population is expected to reach 440 million, that is, close to the current population of the European Union. Despite taking many fruitful measures, especially the expansion of the social insurance and pension programs in the past decade, China is yet come to terms with the aging problem on the cultural and policy levels.

The State Council, China's Cabinet, did issue a document on elderly care in September. But despite having plenty of policy suggestions on developing community-based eldercare, pension service points, care insurance and the like, the document is short on real details.

However, one relatively small proposal - a pilot plan for so-called reverse mortgages - caught the eye of social media, sparking a heated public debate based on the common public misperception of senior citizens exchanging their homes for financing their beds in nursing homes. Before making an assessment if the policy is relevant and appropriate for China, we should first contribute to a better understanding of what the policy entails.

In Western countries, particularly the United States and the United Kingdom, which have a high percentage of home ownership, reverse mortgage or equity release plans has been around for at least 25 years. The idea is relatively simple based on the lifecycle theory of consumption.

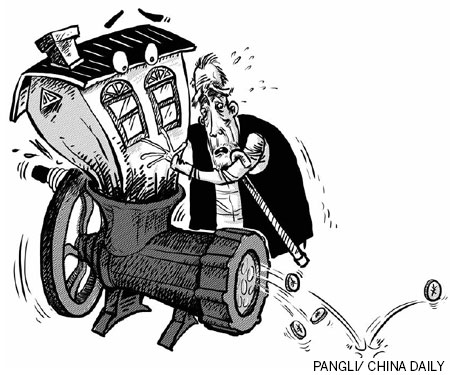

People accumulate assets during their working lives. After retirement, however, most people de-cumulate assets as their incomes fall. But the biggest asset that people have is a house or apartment, which cannot be easily turned into cash. Many senior citizens try to reduce their expenses by selling their house and moving to a smaller one only to realize that the transactional costs of shifting are high and the property market is crowded with individuals and young families desperate to buy a house. Under such circumstances, the elderly may not be able to make significantly large capital gains.

Above all, a person's home is often important to his/her emotional health and stability. There are many examples of even physically fit people dying within a short time of moving out of their home or community.

Equity release plans are aimed at preventing such outcomes. In much the same way that pension companies provide annuity in exchange for a pot of liquid assets, a lender (usually a bank or insurance company) provides regular annual income to the homeowner (both spouses in most cases) which is recovered with interest upon the homeowner's death. Like annuity payments, such plans have the element of uncertainly in terms of time because nobody can tell the age at which a person or couple will die or predict the real value of the property in order to fix the right amount for annuity. With financial assets, banks have flexibility with their decisions on how to manage and liquidate their asset portfolios. But in equity release plans, they cannot exercise such flexibility because they can liquidate assets only upon the death of the borrower/s, which could be further complicated by adverse market conditions.

Besides, equity release requires a stable and mature secondary housing market, which does not exist in China. A huge number of new housing units across the country are lying unsold, compromising the development of a stable secondary property market in the medium term. Building quality (and its impact on valuation) is another major problem in China, as is people's blind preference for new housing. Most importantly, the 70-year leasehold term for property will seriously constrain the value of secondhand houses even if other aspects of the market were to become stable.

There are problems on the demand side too. Chinese people have much the same cultural view as their American and European counterparts, that while it's fine to spend cash from bank accounts or long-term savings like insurance policies, property is something that should be left as inheritance to the next generation. Perhaps this culture will gradually change with the new generations becoming more prosperous and buying their own property. But that is not happening anytime soon.

Moreover, lurking in the background is the fear that the scheme may not be voluntary and will become compulsory. This raises the specter of fraud and greed as banks, like land speculators, force unfair valuation on the weak and defenseless senior citizens, and people think the cash provided cannot be spent on holidays or to buy gifts for their children and grandchildren but to pay only for their own care. This fear in all likelihood is permeating public perception. And it could break one of the key social compacts underpinning China's strict family planning policy - Chinese people choose not to have more children on the promise that the State would care for them in their old age. Being seen as backtracking on that promise is a highly sensitive matter.

Caring for the elderly, however, should not be the sole burden of the younger generation. There must be intergenerational equity, and better-off senior citizens should be expected to contribute a reasonable amount for their own care. As such, a pilot reverse mortgage plan in Shanghai or Beijing may be worth trying, for it could play some part in financing eldercare in urban areas in the long term.

But the plan should not detract from other potential initiatives for financing sustainable community care. Many developed countries already have substantial experience of elderly care and China needs to actively explore all these and its own variations whether its long-term care insurance plans, as seen in Germany, the engagement of non-governmental sectors as in the UK or US, or through limited income taxation on well-off retirees.

Grayson Clarke is an international public finance consultant based in Kuala Lumpur, and Matthias Stepan is a researcher at Vrije University Amsterdam, specializing in the governance of social security systems.

(China Daily USA 10/14/2013 page12)

Senate leads hunt for shutdown and debt deal

Senate leads hunt for shutdown and debt deal

Chinese education for Thai students

Chinese education for Thai students

Rioting erupts in Moscow

Rioting erupts in Moscow

Djokovic retains Shanghai Masters title

Djokovic retains Shanghai Masters title

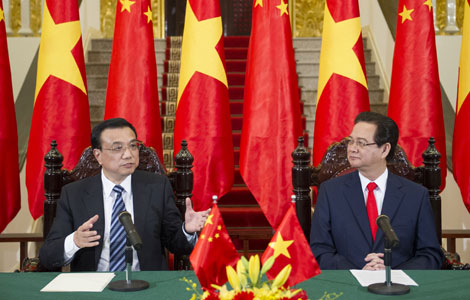

Working group to discuss sea issues

Working group to discuss sea issues

Draft regulation raises fines for polluters

Draft regulation raises fines for polluters

Other measures for the capital to become green

Other measures for the capital to become green

Colombian takes wingsuit crown

Colombian takes wingsuit crown

Most Viewed

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|

Today's Top News

90 killed in stampede in central India

Senate leader 'confident' fiscal crisis can be averted

China's Sept CPI rose 3.1%

No new findings over Arafat's death: official

Chinese firm joins UK airport enterprise

Working group to discuss sea issues

Man hospitalized years after amputating own leg

Detained US citizen dies in Egypt

US Weekly

|

|