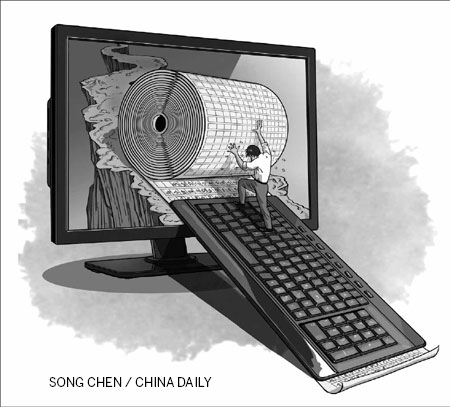

Writers chase their authorial dreams online

Updated: 2013-10-10 07:41

By Yang Yang (China Daily)

|

||||||||

Changing world of publishing offers new possibilities for success, Yang Yang reports in Beijing.

Eight years have passed since Zuo Lei arrived in Beijing after graduating from a college in Shandong province. Working as a director at a TV station in late 2012, the 31-year-old made a difficult decision. He quit his job and became a full-time writer on a professional online literature platform that specializes in voluminous novels updated daily.

"Writing stories has been my dream since I was very young. Although, as a TV director, I could also tell stories, there were too many restrictions," he said. "I have a very strong desire to share my stories with other people, and online literature platforms offer me the chance to do so while guaranteeing a regular income.

Zuo, who writes around 6,000 words a day, can earn about 4,000 yuan ($650) a month, a little less than in his previous job. However, he pointed out that he is just starting out and as his story develops and he writes more, he will gain more readers and better income.

Some popular Chinese online writers can make more than 30 million yuan in a five-year period, not only from readers' online payments, but also from the royalties paid by publishers of books and comics, video game developers and film and TV rights.

The British writer E.L. James, author of the Fifty Shades Trilogy, which sold more than 70 million copies in eight months, topped the list of the world's best-paid authors in 2013, earning an estimated $95 million, according to Forbes. James originally published the story episodically on websites under the pen name of Snowqueens Icedragon. A film adaptation is scheduled to hit the big screen in August.

One of Zuo Lei's models in China is Yang Hao, who writes online under the name Sanjiedashi. After five years of diligent writing, Sanjiedashi, which means Master of Three Commandments, now earns an annual six-digit income and his three completed online novels have been published as conventional books.

Yang said that despite the explosion in online literature during the past 10 years and the tremendous market potential that has attracted more writers and funding, the format is unable to enter the mainstream literary world, which is still dominated by traditional publishing houses. The main reason for this is the generally low quality of work on offer.

Spurred by their falling market share and revenues, traditional publishers are seeking to cooperate with online platforms. The Internet offers quicker and wider access to a growing number of readers, but to obtain recognition from mainstream readers, online novels also need a traditional print run.

"Undoubtedly, the Internet is the future of the publishing industry and traditional publishers are fighting for a share," said Tan Hao, an independent publisher.

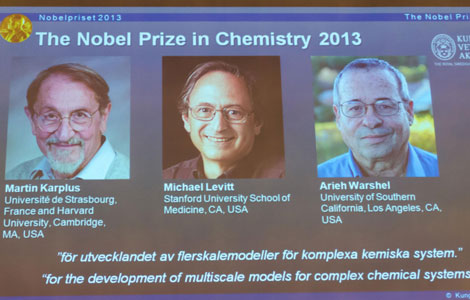

Recently, Tencent, the Internet company with the largest user base in China, invited famous Chinese writers, such as the Nobel laureate Mo Yan, Su Tong, Ah Lai and Liu Zhenyun, to publish their works on its online platforms. But for these writers, online platforms are more akin to publishing channels than creative spaces.

"Apart from reading the news and checking e-mails, I have nothing to do with the Internet," said Mo.

"Technology will inevitably exert an influence on the creation of literature, to cater to 'fast-food reading' (for those readers who enjoy disposable, easily digestible literature), writers will make changes in style and language, but I think the influence is limited. I am personally very optimistic because I don't think the traditional writing style will disappear quickly, leaving books simply as room furnishings."

Mainstream literature, represented by serious writing, is still reaching readers through traditional publishers.

"Economically, printed books account for 99 percent of the consumption of serious literature, especially in Chinese. So, for serious literature, there must be a traditional publishing house and a traditional writer and even if the author decides to publish online, it must be based on traditional publications," said Chen Yikan, an editor at the Shanghai Translation Publishing House.

For both readers and writers, this is the best time, but also the worst. Indeed, professional online literary websites can provide a "nobody" with the space to share the fruits of their imagination and even make a good living from it. However, the low quality threshold of the online literature world leads to a mixed bag of authors, many of whose works are home to bad taste, arid language and illogical plots.

"Online literature is like an extension of the blogs that were extremely popular years ago. Anyone who wants to share their ideas can write their own novel," said Tan Hao, who is also working on a number of online projects.

Many of Yang Hao's acquaintances are online writers. "I know an elderly lady who spent most of her life in the army. She's telling the story of her life online. That's the best thing about the Internet. It's open to everyone," he said.

The possibility of a rapid rise to fame and fortune that online writing promises is attracting more hopefuls to the game. In 2012, the highest-earning online writer was 32-year-old Zhang Wei, whose nom de plume is Tangjiasanshao, which means The Third Son of the Tang Family. He began his writing career in 2004 and has since written 13 novels of about 30 million characters in total (in China, books are measured by the number of characters, not pages). From 2007 to 2012, his total income was 33 million yuan, he said.

Mo Yan, born in 1955, published his first book in 1981. Media reports suggest that he earned 21.5 million yuan in 2012, making him the second-highest-paid Chinese writer last year. However, while in Stockholm to receive his Nobel Prize, Mo refuted the reports and said, "On hearing the news, I went to the bank to check my account, I wondered disappointedly where all the money had gone".

There are more than 100 registered online original literature platforms in China, and Cloudary, one of the country's largest professional online literary platforms, is home to more than 1.6 million writers, according to Securities Daily.

"It's hard to estimate exactly how many online writers there are in China because there are so many large and small online channels. With such a large number, it's inevitable that outstanding writers are rare and the average quality is low," said Tan.

Most Viewed

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|

Today's Top News

Kerry says US will work to end fiscal crisis

Trending news across China

Americans to name panda cubs at Atlanta zoo

US investors say they are less bullish on China

Obama remarks show China high on agenda

Hong Kong benefits from rising renminbi

WB chief praises China for reforms

China is a major contributor to global growth

US Weekly

|

|