Last of the reindeer hunters

Updated: 2013-10-15 07:22

By Wang Kaihao and Yang Fang (China Daily USA)

|

||||||||

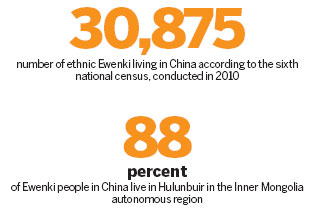

Ewenki herders stick to old way of life as their border forest regions undergo dramatic changes, report Wang Kaihao and Yang Fang in Genhe, Inner Mongolia

Editor's note: This is the ninth in a regular series of reports brought together under the banner "Lost Horizons", which aim to show life in the less-reported areas of the country and to give a voice to those whose words often go unheard. Slideshows and video footage are also available at www.chinadaily.com.cn/video

It was late September and the breathtaking scenery dyed in boundless golden color spread across the Greater Hinggan Mountains in the far northeastern district of Hulunbuir in the Inner Mongolia autonomous region.

As one approaches Genhe, one of China's most northerly county-level administrative districts, a road sign reads "Latitude 50 N". This is the site of China's record low -52.6 C.

Forests cover more than 91 percent of the land in Genhe. Paths through the birch forest were like soft blankets, paved with fallen leaves and withered grass. It was 3:30 pm, and Xiao Liangzhu, a member of the Ewenki ethnic group, had already started preparing dinner in front of a tent.

"The electricity is off because the generator is broken," said Xiao, 58. "I need to hurry before sunset. Once it gets dark, it's time to go to bed."

There are no cellphone signals or any TV channels, let alone an Internet connection. However, life is never boring for Xiao and his wife, because of their beloved reindeers.

Xiao and his brother raise 82 reindeer in this hunting station, one of eight in the area around Genhe. In 1980, the brothers moved from the south of the Greater Hinggan Mountains to the north to join the Aoluguya, an Ewenki tribe that migrated from the far side of the Ergun River, which forms the border between China and Russia, in the late 17th century to escape military conflict.

Compared with 2.5 million reindeer raised by the world's 20 or so ethnic groups in nine countries near the Arctic Circle, the Aoluguya's current 1,200 animals seem a small fragment, but it is the only tribe that still practices reindeer husbandry in China. The animal was the major mode of transport for the locals right up until the 1950s.

"I became a hunter when I was a teenager. I cannot imagine life without the forests or reindeer," said an emotional Xiao. "Every year, I spend one to two months staying with the new-born reindeer from April onward and that close contact means they will stay close to humans later in life.

"Nevertheless, reindeer can never really be tamed. They wander in the forest at night, looking for moss to eat, but they always remember to come back. They go out at night and return around 6 am during the summer."

Xiao moves his tents several times a year to minimize the environmental impact of the animals and the presence of humans.

"Moss needs time to grow. The Ewenki people have always known how to get along with the forest," he said. "We have never caused even a single forest fire here in the many centuries we've lived here."

"This forest is a paradise of precious animal species such as the flying dragon, also known as the hazel grouse, and elk. The environment has remained unchanged all these years, but our lives haven't," he said.

Nostalgia

China launched a nationwide project to preserve forests and counter natural disasters in the late 1990s; the program reduced tree felling in the Greater Hinggan Mountains, which range from the northeast to the southwest of Inner Mongolia for 1,200 km, and are the source of almost all the major rivers in northeastern China.

In 2003, as the country called for "ecological migration" to better protect the forests along the Greater Hinggan Mountains and improve local people's standard of living, two major non-Han ethnic groups that lived in this area, the Ewenki and the Oroqen, were relocated to the towns. The Aoluguya township was originally 200 km from Genhe, but the entire settlement was moved to the western outskirts of the city. Although the tribe had relocated around the forests several times in the preceding decades, the last move was the biggest change of all, because the people had never before lived so close to a city.

Yu Lan, 33, deputy head of the new Aoluguya township government, settled in with the tribe in 1999 and worked as a music teacher at a primary school.

"When I arrived, people's lives were not as poor as the outside world imagined," said Yu, who is Han, but whose husband is Ewenki. "The hunters had a good life selling what they made and gathered in the mountains. Precious antler velvet attracted many customers. Life was cozy, but relatively restricted to a small circle.

"The only major problems were the inconvenience of transport and the aging infrastructure," she recalled. The old township was 17 km from Mangui, the nearest town, and only one train per day ran between Mangui to Genhe.

"An increasing number of local high school students went to Genhe to gain a better education, but shuttling between the two spots was difficult. The power supplies and dams were out of repair. The clinic in the township could only treat minor illnesses and seeing a doctor was very inconvenient in the event of an emergency. "

Each of the 62 families made jobless by the relocation was provided with a free 5-square-meter cabin in the new neighborhood. At first, Xiao welcomed the relocation because of the improved living conditions, but he worried about losing his reindeer.

"Everyone began to raise reindeer in the yards of their new homes," he said. "But you have to realize that reindeer die if they leave the forests, so a short time after the relocation, many people swarmed back to live in the mountains."

Official statistics show that 244 people live in the new township, but some, including Xiao, opt to shuttle between their houses and their homes back at the hunting stations.

However, another change has proved more dramatic for Xiao. In 1996, a law was passed regulating the use of firearms. Following the 2003 relocation, a government order required all the Ewenki's hunting rifles to be taken into "collective custody".

"We are now hunters without guns," said Xiao, looking sullen. "Actually, the guns were not used for hunting in general, they were there to protect us and the reindeer."

In the old days, if a reindeer failed to return from its nocturnal foraging the hunters would search for the missing animal and they always carried guns in case of attack by black bears. Times have changed and now they have no weapons in their hands.

Because of this, Xiao only allows a few of his reindeer to rummage for food in the wild, and vigilantly keeps the rest near his camp. He clearly recalls June 10, 2013, when disaster hit his brother's reindeer.

"It had rained heavily. My sister-in-law was alarmed to see several young reindeer struggling to stand in the muddy ground, so she released them into the forest. And, they met a bear. . .

"Now if I encounter a bear in the forest, the only thing I can do is run away. Therefore, young people no longer dare to chase after missing reindeer.

"Please don't talk about guns anymore," Xiao paused, tears in his eyes. As if on cue, snowflakes begin to fall in the woods.

Yu admitted that the lack of protection is one of the major reasons that an increasing number of the Aoluguya have abandoned reindeer husbandry. Her husband's parents stopped around 2005, but more than 20 families still follow the old traditions today. She added that one family with a herd of about 100 reindeer once lost 38 of them in a bear attack.

"The Aoluguya people consider the loss as part of the natural cycle and thus generally remain calm, but this problem is looming over the whole forest. If we don't come up with a good idea, I'm afraid that reindeer husbandry will finally disappear," she explained.

The hunters have applied to get their guns back, but although the government has promised to resolve the dilemma, Xiao said he will have to wait for an unspecified period of time and he is unsure whether he will ever hold a rifle again.

"My 26-year-old son prefers to live in the town, and even as a child he didn't like shooting," he added.

New ways to live

According to Yu, Aoluguya township began to develop tourism in 2007 as a supplement to reindeer husbandry. A year later a 38-sq-m attic, was added to every cabin in the township, which are decorated in Scandinavian style. More than 20,000 tourists are attracted during the peak season between June and September. While 22 families have turned their dwellings into home-style inns, another 20 have opened stores selling local specialties.

Bulina, 28, opened her inn in 2012, and has earned 20,000 yuan ($3,300) so far. The 28-year-old also works in a reindeer husbandry park nearby for five months each year for a monthly salary of 1,500 yuan.

"In the first class in college, the professor asked us to write down our post-graduation plans," she smiled. "Everyone wrote about their ambitious goals, but my answer was that I would be going back home.

"Aoluguya has such a small population. If all of us choose to leave, what will happen to my hometown?" She stared down at the 1-year-old child in her arms; "I dare not guess whether my daughter will move away, but I will respect her choice."

As the nearest hunting station to the township, Xiao's cabin has become a hot tourist destination, earning him up to 100,000 yuan a year. The local tourism bureau spends 10,000 yuan on each family that still raises deer in the mountains, equipping them with tents and basic facilities to allow tourists to stay in the forest overnight. Many people are introduced to Xiao's services via ads on the Internet, which also promote his business selling antler velvet.

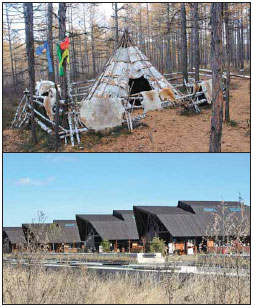

Xiao has erected several teepee-like Ewenki tents, made of birch bark, at the station, but they are only used to illustrate daily life in the olden days to tourists.

A large-scale musical Aoluguya raised the profile of this oft-forgotten corner of China when it debuted in Beijing in 2010. Aoluguya township joined the Association of World Reindeer Herders in 2008, making China the ninth reindeer-husbandry country to join the organization. The fifth quadrennial World Reindeer Herders' Congress was held in the township in July, providing the locals with an international profile.

According to the Aoluguya Declaration, the final resolution made by the congress, reindeer husbandry has been threatened and is disappearing in a number of areas close to the Arctic Circle. It described the situation as "still critical and requiring urgent attention". The association also plans a series of international exchange programs for young Ewenki reindeer herders from China, and has proposed helping them to visit Russia to revitalize relationships.

"We're coordinating with our foreign allies to avoid inbreeding by introducing new reindeer breeds," said Yu. "This small place is getting closer to the big world."

Aoluguya township has even hosted Christmas celebrations for a number of years under the name "China's Home of Santa Claus", hosting parties and reindeer sled races to attract more attention during the long slow winter tourist season, but the event is currently suspended as a new and detailed development plan is formulated. The township also aims to hold an annual sledding competition to widen the brand's influence.

"If we can fully use the tough winter here, our tourism will have another scenario," said Yang Limin, Party chief of Genhe, bemoaning the decline of forestry operations that has dragged Genhe, one of the richest places in Inner Mongolia during the 1980s, from wealth to poverty. The city is now one of poorest county-level administrative districts in the autonomous region.

"We should thank the people of Aoluguya. They have made a great contribution to the development of society by sticking to their homeland and safeguarding this cold forest, a place that was once considered uninhabitable for human beings."

Maintaining traditions

The gradual boom in tourism has also provided impetus for a revival of traditional Ewenki culture. Although boats and clothing made from birch bark are hardly practical in the modern word, the method of manufacture has been preserved by the locals. Dekli, who was taught the traditional skills by her mother, sees great potential for the creation of items closer to a modern aesthetic.

Her studio is filled with various types of ornaments and hanging decorations made from reindeer antlers or bones adorned with delicate carvings. Her pieces were once exhibited in Taiwan, earning great praise, but Dekli is seemingly untroubled about the profits she could make if she moved to a big city and opened a store.

"It is only an expression of my emotions," said the 41-year-old, who has also published many works about Ewenki history. "It is the same with my books. I don't want to be famous, I just write whenever deep thoughts occur in my mind."

Aoluguya townships's last shaman died in 1997, but in common with many Ewenki people, Dekli, whose name means "Holy bird on the Shaman's Costume", is still a fervent believer in shamanism, which emphasizes equality and the interaction between humans and nature.

She said that the artisans were recently offered 1 million yuan to make a shaman's costume, but no one took up the offer.

"We are able to make the costumes, but we won't. The priests are wise and sacred. Worship of them will always run in my blood. It would be blasphemous for us to randomly remake their costumes."

She was delighted to make a trip to an Ewenki village in Russia recently and was excited to find that she could talk to the locals without any obstacle. Frequent contact with Russian traders over the centuries has resulted in the Ewenki borrowing a large number of Russian words. However, according to Yu, the future of this language, which lacks a written system, is not a cause for optimism.

"Children no longer have the environment to speak Ewenki. Few people under the age of 30 are able to speak it fluently. Protection of the language is more difficult than the survival of ethnic music or arts," Yu said, expressing regret that her half-Ewenki daughter only speaks the language brokenly.

In 2007, when only seven children remained at Aoluguya elementary school it was merged with another school in Genhe. However, all fourth-and fifth-grade students at the new school, no matter which ethnic group they belong to, will study Ewenki in the hope of reviving this endangered language.

"People in Aoluguya older than 60 usually have Ewenki names, while many people in the 30 to 50 age group have chosen Han names," said Yu. "But it's good to see people's awareness of their ethnic identity getting stronger.

"All the parents in Aoluguya are giving their children Ewenki names right now," she smiled. "My daughter is called Alina."

Contact the writer at wangkaihao@chinadaily.com.cn

|

Reindeer belonging to Xiao Liangzhu, a member of the Ewenki ethnic group in the Greater Hinggan Mountains in the far northeastern district of Hulunbuir of the Inner Mongolia autonomous region. Wang Kaihao / China Daily |

|

Xiao Liangzhu tends to one of his reindeer at his hunting lodge near Aoluguya township in the Inner Mongolia autonomous region. Wang Kaihao / China Daily |

|

Dekli, one of the best-known artisans, makes Ewenki decorations in Aoluguya. Wang Kaihao / China Daily |

|

Ewenki in Aoluguya used to live in tents (top) in the forests, but now most have moved to a new settlement (above) in Genhe city. Photos by Wang Kaihao / China Daily |

|

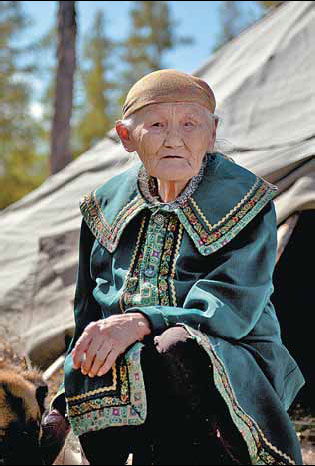

Maria Suo is the matriarch of the Aoluguya. She has lived in the area for more than 90 years. Provided to China Daily |

(China Daily USA 10/15/2013 page7)

New Yorkers celebrates Columbus Day

New Yorkers celebrates Columbus Day

Smartphone firm rockets into the US

Smartphone firm rockets into the US

Storm swamps car insurance firms

Storm swamps car insurance firms

3 US economists share 2013 Nobel Prize in Economics

3 US economists share 2013 Nobel Prize in Economics

Canton Fair to promote yuan use

Canton Fair to promote yuan use

Vintage cars gather in downtown Beijing

Vintage cars gather in downtown Beijing

Senate leads hunt for shutdown and debt deal

Senate leads hunt for shutdown and debt deal

Chinese education for Thai students

Chinese education for Thai students

Most Viewed

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|

Today's Top News

At least 20 killed in strong Philippine quake

Airport bomber sentenced to 6 years in jail

Conference salutes China-US ties progress

The itch that Kobe just can't scratch

Cosmetics is a mirror to China's economy

Chinese may have discovered the future of batteries

Row over NASA's ban should be wake-up call

Baidu 'worry ranking' exposes netizen anxieties

US Weekly

|

|