The road once taken

Updated: 2013-10-29 07:17

By Cui Jia (China Daily)

|

||||||||

Editor's note: This is the 10th in a regular series of reports brought together under the banner "Lost Horizons", which aim to show life in the less-reported areas of the country and to give a voice to those whose words often go unheard. Slideshows and video footage are also available at www.chinadaily.com.cn/video

Soldiers' descendants revisit route their ancestors traveled 250 years ago to defend the nation, Cui Jia reports from Xinjiang and Mongolia

Fu Shihao ran around his grandfather's courtyard proudly displaying a yellow "honor belt", which he had to wrap twice around his tiny waist just to keep in place.

The belt is the property of the 5-year-old's aunt, who lives in the Qapqal Xibe autonomous county in the Xinjiang Uygur autonomous region.

She is one of eight members of the Xibe ethnic group awarded the honor after retracing a journey made by their ancestors almost 250 years ago.

On the belt buckle is carved the image of a mythical creature whose Xibe name has been lost through the generations. It has a body shaped like a horse, but its features are closer to those of a lion or dog, and it has wings and a unicorn's horn.

The animal was once revered by the Xibe people, who told of how it saved their forefathers by guiding them safely out of a deep forest when they were lost.

Most of the Xibe living in Northeast China, where the creature worked its magic, have adopted the lifestyle of the Han ethnic group, losing their traditions in the process, so only a few Xibe people recognize the animal.

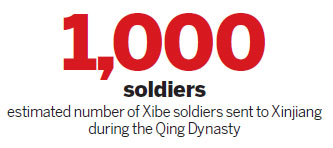

However, it would have been familiar to the more than 1,000 Xibe soldiers and their 3,000 relatives who were dispatched to Xinjiang in 1764 to guard the nation's borders.

Bei Xian Na ("Hello" in the Xibe language), said little Shihao, as he left off careering around the courtyard to greet his honored aunt, Xue Mei. Nowadays, the Xibe language is only spoken in Qapqal, which is home to approximately 20,000 Xibe people, roughly 12 percent of the ethnic group's total population in China.

Xue, 43, who works for a large State-owned enterprise in Beijing, had arrived just in time for a family lunch at the house in which she was raised. Along with traditional Xibe pancakes, Xue's father, Fu Zhangyong, 74, offered his daughter Kazak milk tea, a favorite drink among the Xibe who have lived alongside members of the Kazak ethnic group for centuries. The rich grasslands of Qapqal, in Ily Kazak autonomous prefecture, provide a natural home for the nomadic Kazaks.

Little did the family know, but Xue had a surprise for her father, a 10th-generation descendant of the soldiers whose deployment was specifically requested by an Ily-based Qing Dynasty General, Mingrui.

The 'ancestral' stone

In a letter to Emperor Qianlong praising the Xibe, Mingrui wrote: "The Xibe people based in Shengjing (now Shenyang, the capital of the northeastern province of Liaoning) are experts in archery and horsemanship. I believe their skills could be put to good use defending the border." The Emperor was impressed and granted the request.

After lunch, Xue quietly asked her father to sit in his chair under a grape trellis in the middle of the courtyard. She then pulled something wrapped in a red cloth from her pocket before suddenly kneeling and carefully unveiling the contents.

She held out the offering in both hands: It was a dark red pebble she had picked up on the banks of the Kherlen River in Mongolia, the first watercourse encountered by the soldier-travelers' massive caravan, which is estimated to have been 12 kilometers long at some points in the journey. They used the river as a guide as they traveled across Mongolia, which was part of China at the time.

When Xue explained to her father that their ancestors might have even stepped on the pebble or dampened it with their sweat or tears 249 years ago, the elderly patriarch began to cry as he held it in his shaking hands. "It is now the most precious thing in our house," he said, gently rubbing the smooth surface of the stone.

In Qapqal, almost everyone dreams of retracing the steps of their famous ancestors, who bade farewell to their relatives and traveled more than 5,000 km across Mongolia to Xinjiang, a place about which they were entirely ignorant. "The Xibe people sacrificed their homes and lives for the good of the nation. We are born soldiers, so when the country needed us there was no room for hesitation," said Lao (old) Fu.

Blurred identity

Of the eight modern-day Xibe who completed the emotional journey in August, four came from Qapqal while the rest were natives of Northeast China. They said their ethnic identity has become so blurred that they have had to search hard to reclaim it.

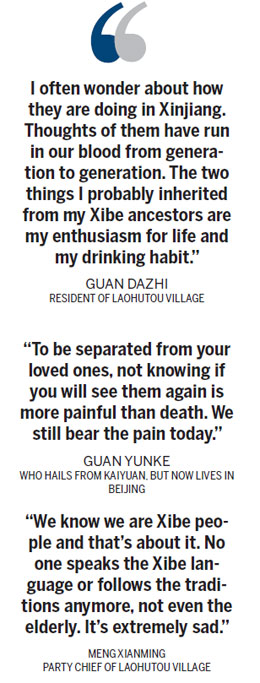

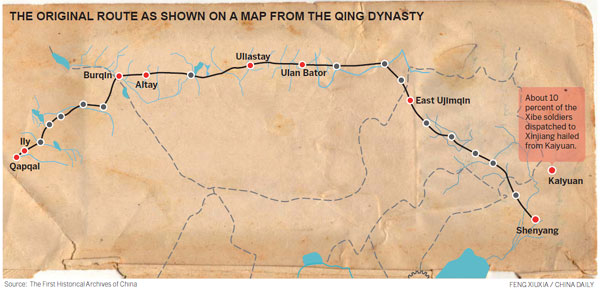

"We know we are Xibe people and that's about it. No one speaks the Xibe language or follows the traditions anymore, not even the elderly. It's extremely sad," said Meng Xianming, the Party chief of Laohutou village in Kaiyuan city, Liaoning province. About 10 percent of the Xibe soldiers dispatched to Xinjiang hailed from Kaiyuan.

Laohutou has 1,816 residents, and 1,642 of them are Xibe. Meng, 46, was determined to revive the ethnic culture in the village by following his ancestors' original route north and then westward.

As the group traveled along the country roads to Laohutou and saw the flowing canals and corn growing on both sides, the Xinjiang members of the party were surprised at the familiarity of the scene.

"It was just like Qapqal," said Zhang Xuewei, 44, one of only three women in the group, who works for an international organization in Beijing. The Xibe who migrated westward replicated their northeastern lifestyle by digging canals and irrigating the farmland with water from the Ily River.

Because the Xibe in Xinjiang live by farming rather than herding they have never had disputes over grassland rights, so their relationship with the Kazaks has always been harmonious, according to Gorlod Gelig, 52, a researcher into the lives of nomadic people in China and Mongolia, who is based in Hohhot, the capital of the Inner Mongolia autonomous region.

In Laohutou, the villagers were curious about their visitors, who, after all, might be their blood relatives. Guan Dazhi, 36, displayed his family tree, written on a piece of cloth that had turned yellow over time. Circles were marked beside the names of his male ancestors who were sent to Xinjiang.

"If the family had two boys, one had to go to Xinjiang, but they never came back," said Guan in his thick northeastern accent as he carefully refolded the fragile piece of cloth. He hoped that Meng's journey to Qapqal would help in the search for his long-lost relatives.

"I often wonder about how they are doing in Xinjiang. Thoughts of them have run in our blood from generation to generation. The two things I probably inherited from my Xibe ancestors are my enthusiasm for life and my drinking habit," he laughed.

A united front

One theory about the rapid decline of the traditions and language of the northeastern Xibe is that many of them fought in the War of Resistance against Japanese Aggression (1937-1945) when ethnic identity was the last thing on their minds and they adopted the language and lifestyle of their Han comrades in arms, said Sarkozi Ildiko Gyongyver, an anthropologist from the University of Pecs in Hungary, who has been studying the Xibe people in Qapqal since 2010.

"By contrast, however, the Xibe population in Xinjiang is very small, which has forced them to emphasize their ethnic identity so they can present a united front to any possible threat," said the 35-year-old, who currently lives in Qapqal.

Before joining his fellow travelers to pay respects at the Xibe temple in Shenyang, where their ancestors bade farewell to their relatives, on April 18 - the date upon which the original journey began in the Chinese lunar calender - to kick off the modern-day journey, Meng took two bags of corn and rice seeds from Laohutou with him, planning to plant them in Xinjiang, just like the old times.

The group intended to follow the exact route that the Xibe soldiers and their families had taken, according to a detailed map from the Qing Dynasty.

"To be separated from your loved ones, not knowing if you will see them again is more painful than death. We still bear the pain today," said Guan Yunke, 60, who hails from Kaiyuan, but now lives in Beijing where he owns an art gallery.

Some people claimed the emperor had promised the soldiers and their families that they would be free to return home after 60 years of service, but no document has ever been found to support that theory, he added.

"The early generations of the Xibe people in Xinjiang were cremated when they died so their ashes could be carried back to Northeast China, but later burial became the norm and they decided to call Qapqal home," added Guan.

At the China-Mongolia border, He Xiaodong from Qapqal was busy talking on his cellphone with the staff at his restaurant in Beijing which specializes in Xibe cuisine. He was anxious to conclude his business before crossing the border and incurring extra roaming charges.

The 39-year-old spoke a mixture of Mandarin and Xibe. "The fact is that we can't speak the Xibe language as well as our parents did and the next generation is likely to be even worse because Mandarin and English are more useful than Xibe," he explained with a bittersweet smile.

Four SUVs and the Mongolian drivers were waiting for the group at Zhuengadabuqi land port in Inner Mongolia. The vehicles had been modified with reinforced internal bars to minimize damage and injury in the event the SUVs overturned, the bars are a must-have feature for vehicles in Mongolia.

"Our ancestors only had horses and oxcarts, but we have SUVs, which is such a luxury - mind you, they didn't need visas," laughed He, while getting his passport out ready for stamping.

As soon as the fleet exited China, the sealed road disappeared and the SUVs began to cruise across the vast grassland, following the tracks made by other vehicles. There were no road signs to guide them.

Treasured possession

Heymdrog, one of the drivers, said Mongolians treat the grassland as a treasured possession so most of it has been left untouched, even though there are large deposits of coal underground. Mongolia is the most sparsely populated country in the world and more than 45 percent of its population of 2.9 million lives in the capital Ulan Bator.

The green and yellow grassland stretched as far the eye could see and a special fragrance hung in the air. "This little-changed landscape might be exactly what my ancestors would have seen," said He, who became emotional while looking out the window.

After driving in the direction of Ulan Bator for five hours, the weather changed dramatically. First, rain began to pour, quickly followed by hailstones. The horses belonging to the local herdsmen grouped together and turn their heads away from the driving rain to protect their eyes. The experienced SUV drivers followed the horses' example; unlike their ancestors, the modern-day travelers didn't need to hide under their vehicles for shelter during the storm.

When the rain had stopped, a layer of fine mist rose from the grass and quickly disappeared. The fleet of SUVs continued heading westward and, after cresting a small hill, He suddenly asked his driver to stop because he'd spotted something in the sky ahead of them.

"Don't the clouds look like a fleet of oxcarts with people on them?" he asked the others, who all agreed. "Maybe it's a sign that they (the ancestors) are with us now," muttered He, as if to himself.

As the sky grew dark, illuminated occasionally by bolts of lightning, the group decided to halt for the day and camp in the wilderness. It was the first time that many of them had erected a tent, but with the help of modern technology and materials, the difficulties they faced were as nothing compared with those faced by their ancestors, they said.

The next day, just before sunset, the group arrived at the Kherlen River, the SUVs covered in mud from top to bottom.

Although it was just 50 km to Ulan Bator and the sealed road had reappeared, the group decided to camp on the banks of the river, which occupies a special place in Xibe folklore because of its significance to the original travelers.

The Xibe soldiers and their relatives made their way across Mongolia by following rivers and visiting coaching inns run by the Qing government to acquire water and other supplies. The inns, which were designed as conduits for military information and mail, big and small, all had one feature in common - a well. These abandoned water sources can still be seen on the grassland, marking the sites of former official supply points.

A bonfire was lit and the modern-day travelers gathered around it, holding up their wet sleeping bags and clothing to dry, just as their ancestors did.

Dancing and singing

A little later, the Xibe from Xinjiang began to dance around the flames, singing about the canals the ethnic group built in Qapqal. Meng was invited to join in, but politely refused because he didn't know the dances or refrains. "I so wish I could be as Xibe as them," he whispered.

The following morning, as Xue walked along the riverbank to pick up a pebble for her father, she was stopped by Heymdrog. "You cannot take anything away from the grassland," he said politely, but firmly. After explaining why she wanted the pebble, he relented and allowed her to take just one.

Another important stop for the Xibe on the westward journey was Uliastay, where the original travelers stayed for six months to sit out the harsh winter and welcome the birth of more than 350 babies, some of whom later died on the road. About one in 10 of the Xibe in Qapqal are descended from those babies.

The group arrived at Uliastay, deep in the heart of the mountains, in the middle of the night after 17 hours of driving across the grassland and the Gobi desert. Despite their fatigue, many were unable to sleep in the traditional Mongolian yurts because they were excited about paying their respects to their ancestors the next morning.

Shortly after sunrise, Zhang began to line up the food for the ceremony, which took place in the river valley where the locals claimed the original travelers had stayed. One of the important offerings was garlic, which is indispensable to Xibe people, no matter where they are from.

The group lined up along the riverbank. One by one they knelt and bowed to the west and the east. "Your children have finally come to see you. We apologize for keeping you waiting this long," said a tearful Guan, pouring alcohol onto the riverbank.

Uliastay was once the base of a Qing Dynasty general, Chenggun Zhabu. A stone carved with the Chinese characters Qinglong Qiao (Black Dragon Bridge) can still be seen in the city center, but the general's manor has turned to rubble.

The group trekked down to the ruins of the manor on foot. Their ancestors had also come here, to ask the general to replace their sick and dying animals so they could complete their mission faster. Small pieces of half-buried china, bearing colored patterns, reflected the sunlight. The sight immediately reconnected the Xibe with the Qing Dynasty, famous for its expertise with ceramics.

After 13 days of traveling across Northwest China and Mongolia, the eight Xibe people finally arrived at Qapqal. The same journey took their ancestors 16 months to complete; many of the women took the babies born in Uliastay to report to General Mingrui, because their fathers had died on the road. The babies became known as "the youngest soldiers in the world".

The Xibe built watchtowers known as kalun along the border, and the ruins of Nadanmu Kalun, made of mud, are just 10 km away from the current Chinese-Kazakhstan border. Only seven kalun remain in Qapqal.

Passing on the spirit

Zha Jinghai, 46, who was born in Qapqal but now lives in Beijing, walked through the ruins where he and his childhood friends once played with bows and arrows. This time, though, things felt different, "I understand the meaning of the kalun more now I've been through this journey. The kalun mark the border, which must be guarded by Chinese people irrespective of which ethnic group they are from or the sacrifices they will have to make," said the telecommunications engineer, the quiver in his voice betraying his emotion.

Although his son was born in Beijing, Zha insisted on teaching the boy to speak and write in the Xibe language. "We have a responsibility to pass on the Xibe spirit. The language is the foundation of that," he said.

But Wu Yuanfeng, an ethnic Xibe and a researcher at the First Historical Archives of China, was not optimistic about the future of the language, which is very closely related to Manchu, the language of the Qing Dynasty rulers. "There is no use for the language outside Qapqal, so sooner or later people will stop using it. It's how the world is going, which is sad to see but something we have to admit."

Wu added that very few Manchu in China can speak or write in the language nowadays, so translating documents from the Qing Dynasty has become the responsibility of the Xibe people. "There are about 200,000 to 300,000 of these documents still to be translated and analyzed. Some of them might just hold the answers to China's border disputes, past and present."

Xue said all the Xibe can do now is try to slow the process of ethnic decay. She sat and watched her young nephew showing off the belt. "He can learn about our language when he goes to the primary and middle schools in Qapqal. Our future is right there," she said, nodding toward the 5-year-old and smiling.

Contact the writer at cuijia@chinadaily.com.cn

|

Members of the Xibe ethnic group cook at a bonfire on the banks of the Kherlen River in Mongolia as they journey from Liaoning province to the far west of China. Cui Meng / China Daily |

|

The travellers at their camp alongside the Kherlen River in Mongolia. Photos by Cui Meng / China Daily |

|

An elderly man from the Xibe ethnic group relates a story in the local language. |

|

Xue Mei presents a pebble she picked up on the banks of the Kherlen River in Mongolia to her father, who is a 10th-generation descendant of the original Xibe soldiers. |

|

Guan Yunke (center) and his fellow travelers check a map after crossing into Mongolia. |

(China Daily USA 10/29/2013 page7)

ABC apologizes for 'Kimmel' joke

ABC apologizes for 'Kimmel' joke

Ellis Island reopens for 1st time since Sandy

Ellis Island reopens for 1st time since Sandy Lang Lang named UN Messenger of Peace

Lang Lang named UN Messenger of Peace

Snowfall hits many areas of Tibet

Snowfall hits many areas of Tibet  Antiquated ideas source of Abe strategy

Antiquated ideas source of Abe strategy

Storm wrecks havoc in S Britain, leaving 4 dead

Storm wrecks havoc in S Britain, leaving 4 dead

Women's congress aims to close income gap, lift status

Women's congress aims to close income gap, lift status

Sao Paulo Fashion Week held in Brazil

Sao Paulo Fashion Week held in Brazil

Most Viewed

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|

Today's Top News

Albright counsels fact not myth in relations

Is Obama's lack of transparency really his fault?

San Diego Symphony debuts at Carnegie

Lang Lang takes on UN `Messenger of Peace’ role

At 72, China's 'Liberace' still wows fans

Penn State: 26 people get $59.7m over Sandusky

China providing space training

Miscommunication causes conflicts

US Weekly

|

|