Still the punchline, but fighting back

Updated: 2013-11-29 12:07

By Kelly Chung Dawson (China Daily USA)

|

||||||||

|

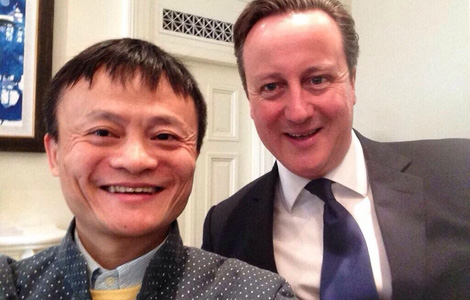

Top and above right: Protesters (top photo and bottom right) gathered outside City Hall in San Jose, California, on Nov 1, demanding ABCTV fire Jimmy Kimmel for his late night comedy segment in which a 6-year-old boy suggested "kill everyone in China" as a way for the US to repay its $1.3 trillion debts to China; above left: People participate in another protest in Los Angeles on Nov9. Photos By Yu Wei, Wang Jun / China Daily |

Jokes about Chinese Americans often get a pass because of the rising success of China and the Chinese Diaspora, but many are fighting back by speaking up, reports Kelly Chung Dawson from New York.

America has long nurtured a tradition of making fun of those in power, born of an assumption that dominant groups and individuals can not only withstand - but deserve to be - knocked down a peg or two.

In this context a joke about white people is more likely to be viewed as funny than a dig at African Americans, for example.

For Chinese, who are frequently held up in the media narrative to be a rising power and yet continue to face casual discrimination that completely discounts a history of injustice, racism and fear-mongering related to the Yellow Peril, the "joke" can be particularly painful.

In the aftermath of the recent Jimmy Kimmel late-night television incident in which a child suggested killing "everyone in China" to eliminate US debt, many people asked: Would the same joke about black people have aired on a major network?

Probably not, most agreed, because a history of activism and increased cultural sensitivity has made it abundantly clear that a joke about African Americans in the mainstream media can expect an immediate backlash.

The same has not always been true for Asian Americans, who until recently rarely had a voice in public discourse about discrimination.

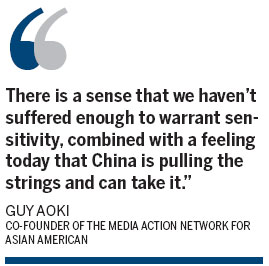

"Chinese Americans are fair game for humor in this country," said Guy Aoki, cofounder of the Media Action Network for Asian Americans. "In the past, so many incidents have been ignored because as a journalist once told me, people don't look at Asians as downtrodden or persecuted. Discrimination against Asian Americans isn't news in the way it is when other minority groups are targeted. There is a sense that we haven't suffered enough to warrant sensitivity, combined with a feeling today that China is pulling the strings and can take it."

Offensive incidents

The Kimmel incident, which inspired thousands to demonstrate in protest against ABC-TV network, is only one of a seemingly never-ending parade of offensive incidents targeting Asian Americans.

Last weekend pop star Katy Perry appeared at the American Music Awards in a hybrid dress featuring both Chinese and Japanese influences, flanked by kimono-clad dancers in a performance of her ode to servility, "Unconditionally." In June, she told Kimmel that she was obsessed with Japanese people, joking that she wanted to "skin" them and "wear [them] like Versace".

The problem isn't isolated to American culture, as evidenced by an incident on Holland's Got Talent last week, in which a judge mocked a Chinese contestant's accent and suggested he perform "number 39 with rice." The judge later chalked it up to "Dutch humor."

In July, the Los Angeles-based pop group Day Above Ground released the music video for their single "Asian Girlz," which managed to hit every stereotype of Asian people in existence: illegal immigrants, women in nail salons, slanted eyes and the hyper-sexualization of Asian women.

Most notable about the recent occurrences is the immediate and vehement reaction of the Asian American community and the increased willingness of mainstream media to publicize that reaction. That desire is also reflected in a growing sense of nationalism and cultural activism in China and among Chinese living in America, of which 76 percent were born in China or Chinese territories, according to a 2010 Pew Research Center study.

"I think the protests of Chinese Americans in the Kimmel incident are directly linked to growing nationalism in China and abroad, because Chinese people simply want to be treated equally," said Yong Chen, a professor in Asian American history at UC Irvine. "Many are realizing that certain elements of Western society view Chinese to be easy targets, and as the Chinese American population grows in size and economic strength, more and more people are realizing they can stand up against injustices."

This is typical of rising groups, said Pat Lucas, a coordinator for study abroad organization CIE.org, and an anthropologist who is studying the increase of nationalistic attitudes among Chinese people.

"With any group, as you become a more important power, you push your elbows out because you feel you finally can," he said. "In America there's a feeling that, 'We're a bigger percent of the population now and it's time for people to take us seriously.' Chinese people are standing up because they don't feel like they have to take crap anymore."

Mainstream US culture has been slow to understand the context in which Chinese Americans and overseas Chinese are "the highest-income, best-educated and fastestgrowing racial group in the US," according to the Pew Research Center, and yet continue to feel disadvantaged as the result of ongoing discrimination that began in the 1800s with the Chinese Exclusion Act and continues today with university quota systems that expect Asian American students to perform at higher levels than other groups. Pervasive stereotypes and pressure to fulfill the "model minority" myth - a term coined in the 1960s to account for the success of Asian immigrants - can shape the Asian American experience, but the kind of discrimination faced within the community can be difficult for non-Asians to sympathize with or understand, said Bethany Lew-Williams, a Northwestern University professor in Asian American studies with a focus on race and migration.

"There is absolutely a disconnect in perceptions," Lew-Williams said "The American mainstream historically and today continues to present Chinese to be a two-sided threat, in which Chinese are perceived to be potentially superior in various ways - academically and economically - while simultaneously dehumanizing Chinese as threatening, or racially inferior. That complexity to the way that Chinese are viewed within the US means that Americans in general are not as astute at picking up anti-Asian racism in humor or otherwise. It's challenging for Americans to even see how racism can affect Chinese people."

Political correctness has yet to include Chinese people, she said. In part, Chinese are viewed as less in need of protection but also less integral to American history. Mockery of Chinese people is rarely categorized as discrimination against 'our people,' she said.

On Nov 10, New England Patriots football player Rob Gronkowski was filmed mocking a Chinese fan for supposedly only being able to cook fried rice. He also casually referred to the fan as "Leslie Chow", an Asian character in the popular film The Hangover. The incident received little attention in the mainstream media, and the fan later said he hadn't been offended, seemingly putting the issue to rest.

Passivity problem

Passivity is part of the problem, said Eddie Huang, a New York City restaurateur and VICE-TV host whose memoir Fresh Off the Boat dealt with the Chinese American experience.

"In the past the Chinese approach was always to keep your head down, to not focus on what people were saying about us because hard work solves everything," he said. "But that's not enough, and fortunately I do think it's coming around. Chinese people are beginning to be more aware of how people view them, and how important identity is, and to not view your race as the butt of any joke but as a source of inspiration and identity."

As that awareness has developed, public perception of China and the Chinese Diaspora has come into sharper relief for many Chinese Americans, he said.

"Many people still feel like Chinese power is a joke to most Americans," he said. "China's growing economic power is constantly questioned in the media, and has resulted in fear and second-guessing rather than respect."

Western attitudes toward China also tend to discount the enormous cultural impact of what many in China call a "century of humiliation" beginning with the Opium Wars, Lucas said. Lingering resentment has contributed to a growing sense of defensiveness that has fueled public furor when Americans are perceived to be attacking China, he said.

When CNN commentator Jack Cafferty called the Chinese government "thugs" in 2008, thousands of Chinese protested in response to what was viewed to be a comment on Chinese character.

"There is plenty of historical evidence for Chinese having been mistreated, and a cultural narrative can develop around a sense of victimization," Lucas said. "When that's part of your historical narrative, that defensiveness can exist right under the skin and prime you to see what that narrative has taught you to see. In the West, it can appear to be an irrational response because of where Chinese are today, but Americans often don't understand. When you look at the history of injustice the Chinese reaction to offenses makes perfect sense."

Lucas also cited the popularity of comedy shows including The Colbert Report as evidence of a particular brand of American humor that caricatures American attitudes.

In the Kimmel incident, the host's long pause after the child's comment was not a sign of agreement but an attempt to "allow for the moment to speak for itself," Lucas believes.

It wouldn't be the first time American humor has confused Chinese viewers and readers. In August, Xinhua earnestly translated and published a satirical "report" from the comedy section of The New Yorker, in which humor writer Andy Borowitz claimed Amazon founder Jeff Bezos had accidentally purchased The Washington Post with a misplaced click of his mouse.

But many experts caution against interpreting reactions to the Kimmel incident in particular through the lens of a supposed Chinese sensitivity or misunderstanding of Western humor, believing the comments to be inexcusable in any context.

"This particular joke, killing an entire nation of people - it's denying them humanity," said Andrea Louie, a professor of anthropology at Michigan State University who studies Chinese identity in both China and the US. "Asians are still seen as 'perpetual foreigners' and often as not really belonging in the US, which can make it very easy for people to joke about them in dehumanizing ways, especially because China is increasingly seen as being in a position of power. Chinese people should not accept being the butt of any joke that emphasizes that they are a foreign threat."

Coverage of China is often driven by an undercurrent of fear-mongering about a dehumanized racial 'other', said Gordon H. Chang, a professor of American history and director of the center for East Asian Studies at Stanford University. He noted a recent New York Times Magazine cover story about Chinese kids learning to play golf, for which the headline was: "Another Way China Dreams of Dominating the World."

"Almost everything you read about China contains reference to it being too ambitious, too hungry, too immoral, too corrupt," he said. "There is an extraordinary amount of fear against what I call the 'New Yellow Peril'. The New York Times Magazine could say that without impunity, because one cannot say anything too extreme about China today. In that context, a joke about killing everyone in China is only funny to many Americans because they feel anxiety toward China."

Chinese nationalism

Interestingly, Chinese nationalism has grown hand-in-hand with a tendency for self-criticism, said Fuji Lozada, a professor of anthropology at Davidson College with a focus on Chinese culture. He cited the self-flagellation on various Chinese Internet sites following the success of Korean pop star PSY's music video and single Gangnam Style, in which commentators questioned China's "inability" to produce a similar hit. Any mention or appearance of Asian people in Western pop culture is scrutinized in great detail in China, he said.

"There continues to be a widespread lack of cultural self-confidence among both Chinese and Chinese Americans, but one that for Chinese is rooted in historical experiences and nationalistic dreams, while for Chinese Americans is rooted in American cultural politics and racism," Lozada said.

"While the Kimmel skit is in poor taste, the raw nerves that it hits among Chinese comes directly from this problem of cultural self-confidence. When combined with Americans' general fear and ignorance about China, these kinds of cultural misunderstandings and conflicts will continue to happen."

Increased education about the Chinese American experience and the various factors that have contributed to resentment toward the West in China would likely go a long way toward tamping down racially insensitive jokes about Chinese people, said C. N. Le, a professor in Asian and Asian American studies at UMass Amherst.

Millennials in particular have grown up in a culture that purports to be "color-blind," and as a result are less conscious of the history of civil rights issues in America.

"The truth is that to move forward, we have to remember the past," he said. "That cliche that those who don't remember history are bound to repeat it is also true of race relations. We can't pretend that our racial and cultural differences don't exist, but as Chinese Americans we can make our voices known, that we're not willing to be punching bags for people's fears and anxieties for the sake of a joke."

Contact the writer at kdawson@chinadailyusa.com

(China Daily USA 11/29/2013 page19)

Most Viewed

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|

Today's Top News

Air identification zone shadows Biden trip

Detroit eligible for bankruptcy

Chinese realtor endows Harvard

China challenges on dumping

Subway project disrupts Chinatown

M&As looking good in China

Peacekeepers depart for Mali

New urbanization plan on the way

US Weekly

|

|