Cities hit hard by smog

Updated: 2013-12-09 07:19

By Wu Wencong (China Daily USA)

|

|||||||||

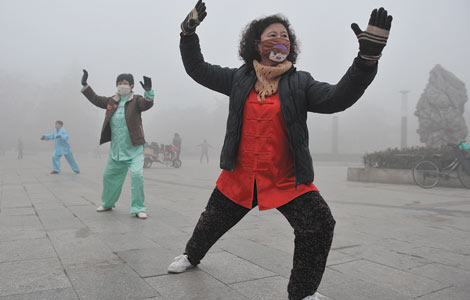

Major urban areas face reduced visibility, increased accidents over the weekend, Wu Wencong reports in Tianjin and Beijing.

China's most developed regions were attacked by smog over the weekend.

A total of 104 cities in 20 provinces in and near China's two largest industrial clusters - the Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei region and the Yangtze River Delta region - fell victim to heavy smog that reduced visibility to less than 10 meters in some places, according to the Environmental Protection Ministry.

The situation will gradually improve from Sunday after wind blows away dirty air, the National Meteorological Center of China Meteorological Administration said on Sunday.

This was the second time heavy smog has covered so many cities this year. Thick haze shrouded many cities for more than 20 days in January, affecting more than 600 million people in 17 provinces, municipalities and autonomous regions.

Air quality issues may not be solved soon, experts say.

China is experiencing what developed countries experienced about 20 to 30 years ago, when smoggy and hazy weather caused by fast urbanization and an unreasonable urban layout frequently occurred, said Peng Yingdeng, an environmental impact assessment expert from the Ministry of Environmental Protection.

"If urban planning does not take the diffusion of pollutants into consideration, smog will plague China for at least another 10 to 20 years," he told Beijing News.

The latest wave of smog, which first swept into Shanghai and Jiangsu province on Dec 1, has caused at least four car accidents due to low visibility, claiming six lives nationwide. The most serious accident was in Jiangsu on Dec 4, which involved almost 20 vehicles and left three dead and many injured.

Highways, water transportation and flights have been suspended or limited in the past few days.

PM2.5 levels in Shanghai hit a record on Dec 1: an average of 582 micrograms per cubic meter for the whole city, with the highest level exceeding 700 in the Putuo district.

The World Health Organization has a safety guideline of 25 for PM2.5, particulate matter smaller than 2.5 microns that can go deep into the lungs.

Policies have been issued in the past few months, including a vow to cut PM2.5 levels in the Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei cluster by 25 percent by 2017 from 2012 levels.

A six-month inspection campaign was launched in October.

Sui Xiaochan, head of the environmental emergency and accident investigation center at the Environmental Protection Ministry, headed a team to inspect Tianjin late last month.

"Stop the car right away and take a photo of that chimney," Sui Xiaochan told the driver, pointing at a chimney some 200 meters away that was giving off thick black smoke.

Ten minutes later, the car stopped outside the chimney, located in a residential district of Tianjin, and Sui and her colleagues soon found themselves inside a coal-fired heating station, built right in the middle of a residential community called Yibaibeili.

Several coal stockpiles stood in the open space between two residential blocks, where in most Chinese communities, a small garden is usually located. The coal was stacked so close to the buildings that one could easily have opened a window and picked up a lump.

It was a heavily polluted day, with PM2.5 readings higher than 300 micrograms per cubic meter, meaning that the level of fine particulate matter smaller than 2.5 microns, fine enough to penetrate the lungs, was high enough to pose a serious health risk. The World Health Organization's safe limit is 25.

The coal, a potential source of dust pollution, lay uncovered and open to the elements. An elderly woman walked slowly past the piles. She was carrying an infant, but neither of them wore protective masks.

Sui asked her assistant to take photos of the stockpiles and of the chimney, which was slightly taller than the six-story building it stood beside. Then she took out her handbook and wrote down the name of the community and the address of the heating station.

Collecting the evidence had taken less than five minutes. We returned to the car and drove away before any of the security staff had even noticed us.

Emergency squad

Sui, a bustling woman in her 50s, is head of the environmental emergency and accident investigation center at the Environmental Protection Ministry in Beijing. The department is charged with dealing with environmental emergencies and pollution inspections.

The pollution sources she chases and the notes she makes will help the ministry evaluate the local government's performance in the control of toxic emissions from a wide range of airborne pollution sources. Sui's work has been bolstered by the new policies issued in September, aimed at "bringing a visible change" to air quality nationwide by 2017.

The ministry's inspection campaign, which runs from October to March, targets sources of airborne pollution and has been timed to coincide with the Chinese winter, when extensive use of coal-fired heating causes levels of haze and smog to climb steeply.

The inspection is mainly focused on the Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei cluster, one of China's most-polluted areas. Cities within the cluster usually occupy six or seven places on the list of the "10 most polluted cities of the month" released by the ministry every four weeks.

In late September, high-ranking officials from municipalities, provinces situated in and around the cluster, plus the Inner Mongolia autonomous region, signed pledges with the central government, vowing to reduce their combined annual consumption of coal by 83 million metric tons by the end of 2017. They also pledged to crack down harder on violations of the environmental regulations.

A month after the policy was announced, six inspection teams, including Sui's, were sent to 12 cities within the cluster to check if local officials are honoring their promises and making every effort to curb air pollution.

Before arriving in Tianjin, the team had spent a week checking on companies emitting airborne pollutants in Qinhuangdao, Hebei province.

The team's task for November was to run through all the districts and counties in the two cities and check whether key coal-burners have modified and upgraded their production lines with desulfurization, denitrification and dust-removal technology, and whether the changes are having the desired effect. The task also included checking dust-prevention measures in areas where raw materials such as coal and sand are stockpiled, and assessing the local authorities' moves to eliminate illegal small-scale polluters.

The checks will be repeated every month. "That means we have to spend half a month working in the field, and the other half writing summaries and preparing for our next field trip," said Sui's colleague, Liu Qing.

The teams have to choose their targets carefully because inspection time is limited. "We have our own criteria for choosing which businesses to inspect," said Sui. "Those with poor record historically, or who have appeared on a list of public tip-offs made via our hotline, or those requiring control at the national level, are very likely to attract our attention."

To ensure the evaluations are impartial and objective, the five-person inspection teams are augmented by an environmental official from a local municipal or provincial government unrelated to the area.

Sui and her six-person crew, which split in two groups to conduct inspections, examined around 50 pollution sources in Tianjin during their six-day tour of duty. Thirty-three sources were found to be violating the environmental laws and regulations, 26 of which were discovered by secret checks.

Color of the smoke

The inspection process is two-pronged: Secret checks are conducted, but the factories are also subject to rigorous inspections attended by local officials. Factory chiefs are questioned and the team conducts spot checks of the data collated daily through online emissions' monitoring.

Secret checks are usually made during the first two days of the inspection team's visit. The local authorities are not notified in advance. The team drives to all parts of the city, looking for chimneys sending out odd-colored smoke. Photos are taken and the locations are logged in preparation for an official, open inspection, as was the case for the heating station with the excessively smoky chimney in Yibaibeili.

"Yellow fumes usually indicate a high level of sulfur, blue means fine particulate matter, and black suggests large particles. Red fumes coincide with a high concentration of powdered iron," explained Sui, sharing a few tips on how to identify the composition of emissions from coal-burning. "Usually, white smoke mainly consists of water vapor, which is harmless."

There are times when the black smoke recorded during a secret check will inexplicably change color on the day of an official inspection, turning white overnight, as happened at the heating station in Yibaibeili.

In such cases, company officials are confronted with photos of the black smoke and required to explain exactly how and why the smoke changed color so quickly. Even if the explanation is accepted, it does not always guarantee that they'll pass the inspection.

"There was an abrupt drop in temperature several days ago, so we started another boiler in response. It's normal for the concentration of emissions from newly fired boilers to be unstable initially," argued Liu Guoming, the heating station chief.

It seemed a reasonable explanation, so Sui didn't pursue the topic further. She did, however, order Liu to build a storage shed for the coal to prevent dust pollution.

"We had a shed until last year," Liu replied. "But the residents complained and said it blocked out the sunlight, so we had to dismantle it."

As the team left the heating station, Sui lowered her voice and reminded her assistant to obtain a copy of the most recent emissions report on the station, even though it had not yet been officially released.

She received the report the following evening. It showed that the level of dust discharged by the heating station was almost six times the national standard, and the level of sulfur dioxide was 12 times higher.

The report was accompanied by news that the district-level environmental protection bureau, under whose jurisdiction the station falls, had imposed a fine of 100,000 yuan ($16,450) because of the high concentration of pollutants in its emissions.

"The local officials acted swiftly," said Sui. "The fine was pretty big for a heating station, and that shows how serious we are about cleaning up the air."

Contact the writer at wuwencong@chinadaily.com.cn

|

Morning exercisers brave heavy smog in Fuyang, Anhui province, on Sunday. Nearly half of the country is choked in some of the worst air this year. Lu Qijian / for China Daily |

|

Chimneys at the Dagang Power Plant in Tianjin, which mainly emit water vapor. Photos by Feng Yongbin / China Daily |

|

A workshop at the Zhasanyoufa Iron and Steel Complex in Tianjin. |

|

Coal stockpiled in an open space in the Yibaibeili community in Tianjin. |

|

The smoking chimney at the Yibaibeili community is one of many pollution sources in Tianjin. |

|

Sui Xiaochan (right) and her inspection team at work at the Tianjin branch of the oil company Sinopec. |

(China Daily USA 12/09/2013 page7)

Most Viewed

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|

Today's Top News

DPRK leader's uncle stripped of all posts

United Way improves traction in China

China's inflation up 3% in Nov

China issues guidelines on official receptions

Winning season for ZTE USA and Rockets

3rd Plenum 'a success': expert

ROK decides to expand air defense zone

Trade surplus hit record high in Nov

US Weekly

|

|