The world's biggest uprooting

Updated: 2014-04-11 11:17

By Amy He (China Daily USA)

|

||||||||

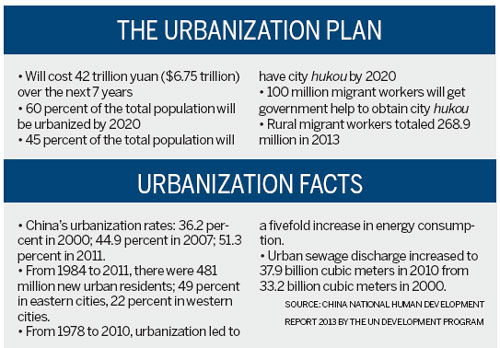

China's new urbanization plan calls for 60 percent of the total population to be moved by 2020, and formidable challenges lie ahead as the world's most-populous country undertakes the biggest human migration in history, AMY HE reports from New York.

If the population figures of Portugal and Sweden were added together, Shanghai's population would still be bigger. Shanghai, the largest city in the world by population, and two other Chinese cities - Beijing and Guangzhou - are among the top 10 most-populous cities in the world.

And under China's first official urbanization plan unveiled in March, China's major cities will most likely get bigger, as the world's most populous country attempts the largest migration in human history, the size, scope, and speed of which has never been untaken by any other country.

The National New-Type Urbanization Plan (2014-2020) wants its urban residents to make up 60 percent of the country's total population by 2020, compared to the current 53.7 percent.

The new proposal also said that residents with official city hukou - China's household registration system - should be around 45 percent of the total population by the end of the decade, up from the 35.7 percent in 2013. The plan calls for 100 million migrant workers and other permanent urban residents obtaining urban hukou with the help of the government.

Chinese officials said that the new urbanization drive will be "people-centered", focusing on giving rural residents who live in cities the same benefits that city residents enjoy.

"Urbanization is the sure route to modernization and an important basis for integrating the urban and rural structures," Premier Li Keqiang said at the National People's Congress leading up to the release of the urbanization plan in March.

The plan issued by the Central Committee of the Communist Party of China and the State Council said that it will focus on "quality" urbanization, as opposed to the urbanization program since 1978 that has resulted in "mistakes" such as water and soil pollution and city congestion.

Hukou policies

Under the new plan, Chinese officials aim to relax hukou policies in small - and medium-sized cities to encourage further urbanization, though they have said that larger cities - Beijing, Shanghai, Guangzhou - with more 5 million in population will maintain strict hukou measures.

When asked if the plan indicates that migrant workers who move to major cities for work will have no chance of getting a city hukou, Huang Ming, vice-minister of public security, said at a press conference in Beijing that "the chances of becoming residents of megacities will not be as big as those in other big cities, and medium and small cities in particular."

Huang said that urbanization across Chinese cities has been "unbalanced" and that big cities with more resources have naturally attracted bigger populations of migrant workers. This has put a strain on these cities that are suffering from environment deterioration and therefore the hukou system will be "under strict control", he said.

But large cities have historically been a major draw for migrant workers looking for more job opportunities as well as better social-welfare benefits, and some urbanization specialists say that maintaining strict measures over big-city populations is misguided, and that the government should actually be looking to make tier-1 cities bigger and denser.

"I'm a little concerned that the control of city size in the larger cities will actually make it harder for China to realize the productivity gains that it needs to grow a sustainable 7 or 7.5 percent for the rest of the decade," said Yukon Huang, senior associate at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. "It's a misconception that Chinese cities are dense; they're actually not that dense," he said. "They're sprawled out and very expansive."

Urban land in Beijing, for example, has increased about sevenfold over the last two decades, while population has only doubled, so if big Chinese cities were actually denser, cities would be more efficient, less polluted and have fewer traffic problems, he said.

"To put a limit on the growth of large cities I don't think is a very wise thing. You don't have such limits in any other country. So that's a question, why do you need one in China?" Huang said.

With so many people spreading out over a large area, local governments need to spend more on building infrastructure and transport links to connect residents, and distance is a challenge when it comes to relaying social services to outer-lying residents.

In a joint report released after the official urbanization plan was unveiled, the World Bank and the Development Research Center of China's State Council (DRC), a state agency, said that in a reform scenario, denser cities will require less infrastructure investment because land will be used more efficiently.

"Land reforms would improve the efficiency of rural and urban land use and increase the compensation rural residents receive from land conversion, thus improving the distribution of income and wealth," according to the World Bank report. "Land reforms will also likely lead to denser cities, which would reduce the energy intensity and car use in cities, thus improving environmental sustainability. And reduced land use for urbanization would leave more land for environmental services and agricultural production."

City density

As Chinese leaders focus on rebalancing China's economy, city density may also play a role in moving the country to a consumption-based economy from an export-driven one.

"Domestic demand is the fundamental drive of our nation's economic development, and urbanization has the greatest potential to expand domestic consumption," the plan said.

According to World Bank estimates, household incomes are higher in cities that are more densely populated and higher-density cities also correlate with higher retail sales per capita.

"Cities offer consumption amenities associated with higher densities, which are associated with higher household incomes," the World Bank reported. "Those higher incomes combined with social interactions associated with higher densities boost the demand for consumption amenities."

Measures to maintain strict population control in large cities prevent market forces from acting to their fullest, running counter to a major point as pledged in the Third Plenum announced last November, urbanization experts said.

"The Third Plenum said to let the market become decisive in allocating resources, and a major resource in China is its people. If you let the market allocate people, essentially you allow the people to go where the jobs are, or where they think the good jobs are, rather than the government artificially restricting it," Huang said.

"There's actually a so-called price of labor, which is wages. When you actually restrict or put rules on where people can live and work, you're actually interfering with the cost and price of workers," he said.

And though big cities are attractive for job opportunities, they won't keep expanding infinitely either, said Pan Qisheng, chair of the department of Urban Planning and Environmental Policy at Texas Southern University and chair of the International Association for China Planning.

Just like market forces may be driving migrants to major cities, it is those same forces that will prevent major cities from growing forever, Pan said. "When a city becomes very dense - especially in the downtown central city area - costs get really high, leading the people to move out from the central city" into the peripheral areas, he said.

So it's not necessary for the government to control city populations, said Pan, nor can they.

"Historical data shows that there's no way for you to control the population in the big cities. There's no way, for sure," he said. "It doesn't matter if we're talking about the US or in China, especially because China said it will become more and more market-oriented."

The majority of China's population lives on the eastern side of the country, which consists of 10 provinces and municipalities, including Beijing, Tianjin, Shanghai, Jiangsu, Fujian, and Guangdong, and has seen continuous urbanization rates since the beginning of the 21st century.

In 2000, the region was urbanizing at a rate of 45.3 percent, which increased to 55 percent in 2007 and, according to latest figures from the China Statistical Yearbook, increased to 60.8 percent in 2011. Within two decades from 1984 to 2011, about 50 percent of the 481 million new urban residents ended up in eastern cities, according to a 2013 urbanization report released by the United Nations Development Program.

"Large cities were bastions of China's urban system early in the reform period, despite restrictive policies at some points, especially to control large cities from the 1980s to the mid-1990s," the report said.

Categorizing residents

One of the other major obstacles in China's urbanization process is how hukou policies will affect new city residents.

Today's hukou system has been in place since the 1950s and residents are categorized as either rural or urban, living and working in the places of their hukou registration. Once urbanization was underway, rural workers could travel to different cities for jobs, but were not given the same access to social benefits enjoyed by city dwellers who had city hukou.

Though it has been possible for workers to obtain city hukou and hukou policies have been relaxed in the 1980s and onwards, issues with hukou still contribute to disparities in income and services provided to rural workers and their families living in new cities.

"Making social entitlements available to all workers and their families in their areas of residence would deepen the human capital base and promote a healthier workforce," said the World Bank-DRC report. "It would improve intergenerational income mobility, reduce future inequalities, and alleviate social tensions."

It suggested that a residence-based system would be more effective than the current system so that money and benefits associated with a worker goes wherever the worker goes. Now resources are allocated based on hukou status, not on a where a person is physically.

"You have a very strange situation. In many rural areas, in many provinces, the local government receives money from the central government for schooling and health for people who don't even exist there," said Huang, who was the World Bank's country director for China, and currently advises the World Bank.

"The people are somewhere else. So if this money was actually reallocated and it went along with where people are, actually, you would have a much easier or more efficient way of providing social services," he said. Social services for urban residents include free schooling, access to basic public health care, medical and retirement pensions and welfare housing.

The World Bank-DRC report said that China has been very successful at "urbanizing employment", but has failed in "urbanizing people", which has ultimately led to income disparities and slow growth of an urban middle class.

The hukou system has historically benefited urban residents, and the rising disparity in service quality has left the migrant population in cities at a disadvantage. Children in migrant families receive poorer education, migrant residents work longer hours for less pay, and it's harder for migrants to purchase homes in cities where they don't have hukou. Only 10 percent of migrants own urban housing, compared to the 90 percent of permanent urban residents, the World Bank-DRC said.

"Hukou's a complicated issue. It's like if you want to board a bus: people who are already sitting on the bus say, 'No, no more people!' But people outside say, 'Well you still have space on the bus, so we would like to board,'" said Zhang Ting-wei, director of Asia and China Research Program at the University of Illinois at Chicago's college of urban planning.

"It's a complicated one and not easy to solve," he said, and it's one of the biggest problems with the new urbanization plan.

The costs of urbanization in China will be huge. Deputy Finance Minister Wang Baoan said that 42 trillion yuan ($6.75 trillion) will be needed to finance urbanization over the next seven years, but many say that the financial benefits of properly developed urban cities are enormous.

"It's an investment worth making, but what we do need is a little less waste," said Edward Glaeser, professor of economics at Harvard University. "We need a little better management and a little less building for building's own sake. Apply that cost-benefit analysis assiduously to every new project, make sure that everything is delivering services that are really helping humanity in the cities," he said.

Ghost towns

Modern-day ghost towns across China have been widely reported on in the last few years, cities where gleaming new apartment buildings and large shopping malls have seen few tenants and customers and remain largely unoccupied.

The environmental costs to China's fast development have also been enormous, resulting in what the government has called "urban disease", which includes environmental pollution, sewage and garbage problems, and traffic congestion.

Air pollution in Beijing and Shanghai hit record highs this year, with thick smog covering the cities and the prospect of moving even more migrants into cities under the new urbanization plan may seem daunting, experts said.

"I don't think anybody has ever urbanized at such a big population at such a fast speed," causing strain on natural resources and adding doubt to whether the environment can handle the new influx of urbanization, said Tunney Lee, former head of the department of urban studies and planning at the Massachussets Institute of Technology.

Compared to the US, which has enforceable environmental laws, "China has strong laws but ones that are difficult to enforce, mostly because the local officials and local factories find it much easier to violate the laws," he said. "That's a big problem."

Local governments need to be differently incentivized, and ultimately, "I can't see how China can afford not to urbanize," said Glaeser. "I think unquestionably urbanization involves an enormous expense but the financial benefits of doing it are enormous."

Abhas Jha, sector manager for transport, urban and disaster risk management for East Asia and the Pacific for the World Bank, agrees.

"The world cannot afford China getting urbanization wrong, because the future of the planet depends on it getting it right," he said.

Contact the writer at amyhe@chinadailyusa.com

|

Newly built apartment buildings in Hefei city, Anhui province. The local government provided 10,734 apartments for more than 20,000 villagers who used to live in an old-city area with poor facilities. Photo by Xinhua |

(China Daily USA 04/11/2014 page19)

People enjoy cherry blossoms in Washington

People enjoy cherry blossoms in Washington

Prince William, Kate unveil portrait of Queen Elizabeth

Prince William, Kate unveil portrait of Queen Elizabeth

Hagel gets recipe of goodwill

Hagel gets recipe of goodwill

US, China firms team up on green truck play

US, China firms team up on green truck play

21 injured in Pennsylvania school

21 injured in Pennsylvania school

Bakers perform with dough in pizza championships

Bakers perform with dough in pizza championships

People enjoy cherry blossoms in Washington

People enjoy cherry blossoms in Washington

Top 10 China archeological discoveries for 2013

Top 10 China archeological discoveries for 2013

Most Viewed

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|

Today's Top News

Another possible signal heard in search

Sebelius resigns after Obamacare woes

Suspect claims he killed 40 as hitman

Soybean talks focus on biotech issues

US Asian carp find plates in China

US, China firms team up on green truck play

Ships sale to Taiwan 'unlikely'

Hagel gets closer to PLA

US Weekly

|

|