Mandarin's moment

Updated: 2014-11-28 11:48

By William Hennelly(China Daily USA)

|

||||||||

Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg addressed a Beijing audience in Mandarin last month. He has been studying a language spoken by 1.3 billion Chinese, and he's not alone. The study of Mandarin in the US is booming, WILLIAM HENNELLY reports from New York.

The pupils in teacher Zhang Shanshan's class at the Hudson Way Immersion School were asked what they needed to do to get more smiley faces on an assignment.

"Ting lao shi (listen to the teacher)," the mostly 4- to 5-year-olds answered uniformly in Mandarin with hardly any foreign accent.

|

Zhang Shanshan teaches Kalen McBrien, 5, basic Mandarin vocabulary about colors and fruits at the Hudson Way Immersion School. Photos by Lu Huiquan / For China Daily |

|

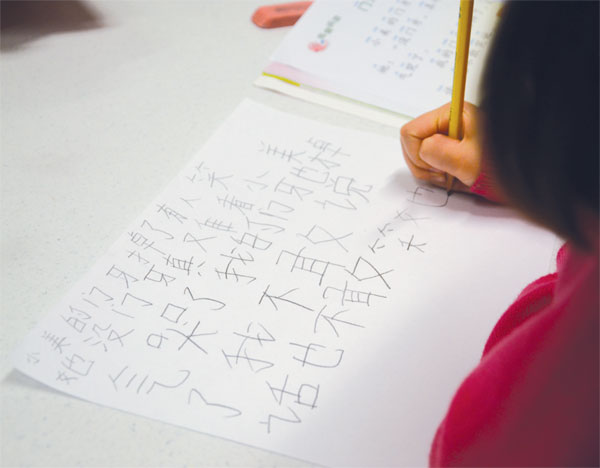

A pupil copies a Chinese passage from a textbook at the Hudson Way School, New York. Pupils are generally capable of understanding and writing short passages by ages 6-7. |

Soon the class began to get noisy. Sensing this, the teacher asked if she should erase some smiley faces off the blackboard, making the lesson longer.

"Bu" (no), the children replied.

"When I first taught this class, they didn't understand what the Chinese storybook was about," Zhang said. "But after two or three months, they can read many of the characters in it."

"By the time they are 9 or 10, if they turn their backs, you can't tell" whether they are native Chinese or not when speaking, said Elizabeth Willaum, a veteran language-immersion expert and director of Hudson Way. "Learning Chinese isn't just about marketability," she said. "When you learn a language, the culture opens to you."

Be it at the private Hudson Way school on Manhattan's Upper West Side or at public schools in Kentucky, Indiana and other states, the study of Mandarin in the United States is booming. In some cases, it is replacing Spanish, French or other languages that have long been more popular in US schools.

"We see a bump in enrollment in the languages of the countries that we see as economic competitors," said Marty Abbott, executive director of the American Council on the Teaching of Foreign Languages (ACTFL) in Alexandria, Virginia.

"In the 1980s, we definitely experienced a surge in Japanese programs," Abbott told China Daily. "I think we're seeing something similar happen with the increased interest in Chinese programs. It reflects China's economic growth, and it's being seen as the economic power to compete with."

Over at Avenues: The World School in Manhattan's Chelsea section more than 300 students from nursery school to grade 3 are enrolled in an alternate-day Mandarin immersion program. The private school has close to 40 Mandarin teachers.

Founded by noted educators and media professionals Chris Whittle, Benno Schmidt and Alan Greenberg, Avenues opened in 2012 with 740 students. It now has 1,270 students from nursery school to grade 12, with plans for schools in 20 "world" cities, including Beijing, Shanghai and Hong Kong.

Chinese an 'essential' language

"Chinese is an essential language of the 21st century world," said Sarah Bayne, global director of Education Design at Avenues. "We are opening one of our world schools in Beijing in 2016, because we recognize the critical importance of China and our relationships there.

"Our model is based on the fact that most of our students come from English-speaking households, so they are all learning Chinese as a second language," she said.

The Internet abounds with stories of increasing demand for Chinese language instruction, and it's not only happening at affluent private schools.

In Louisville, Kentucky, the Hite Elementary School dropped its Spanish classes and switched to Chinese at the beginning of the school year for pupils in grades K-5. The school cited the Chinese counting system as more conducive to learning mathematics, a subject in which Chinese pupils outscore their Western peers on tests.

Minneapolis, Minnesota, has a publicly funded Chinese immersion charter school. The Yinghua School (Yinghua means English-Chinese in Mandarin) was featured in an Oct 26 New York Times article.

In Los Angeles, Yoyo Chinese, a video-centered online Mandarin instructional program, announced on Oct 30 that 7 million lessons have been taken on its website.

"Chinese students learn English in high school, read English literature, watch American television programs, and immerse themselves in American culture," saidYangyang Cheng, founder and CEO of Yoyo Chinese, in a press release."On the other hand, how much do Americans know about China? English speakers learning Chinese have recognized this knowledge gap prevents them from accessing a large percent of the world's population, as well as an entire reservoir of knowledge contained within 5,000 years of history."

In New York City during the 2013-2014 school year, 10,583 students took Chinese language courses across 69 middle and high schools, according to Will Mantell, a spokesman for the city's public schools. That includes both Mandarin and Cantonese courses and Chinese-language instruction for students who are studying it as a foreign language, as well as students whose home language is Chinese.

"Part of our Chinese-language instruction is in bilingual programs that strengthen English language learners' native language development and content knowledge while they build their social and academic English skills," he wrote in an e-mail to China Daily. The bilingual programs may also include non-language courses taught in Chinese, for example, math taught in Mandarin.

New York had 41 Chinese bilingual programs in the 2013-2014 school year - 20 were in elementary schools, 18 in high schools and three in middle schools. Of the bilingual programs, 17 were in Brooklyn, while Manhattan and Queens had 12 apiece.

Going global, too

In Sao Joao da Madei, Portugal, a shoemaking capital, the study of Mandarin is mandatory for 8- and 9-year-olds. The Chinese taste for luxury items extends to fancy Portuguese shoes, which are considered second-best in the world to Italian shoes. The Portuguese deduce that Mandarin will help them expand their shoe market in China, which, according to Agence France-Presse, went from 10,000 pairs in 2011 to 170,000 pairs in 2013.

Recent research by the British Council and Hanban found that 3 percent of primary schools, 6 percent of state secondary schools and 10 percent of independent schools offer Mandarin courses, China Daily reported. Over the next five to 10 years, those numbers are expected to grow by 4 percent to 8 percent.

"I want Britain linked up to the world's fast-growing economies, and that includes our young people learning the languages to seal tomorrow's business deals," UK Prime Minister David Cameron said in 2013.

"By the time the children born today leave school, China is set to be the world's largest economy. So it's time to look beyond the traditional focus on French and German and get many more children learning Mandarin."

In South Korea, the number of people taking the official Chinese proficiency test has risen to 110,000 in 2013 from 400 in 1993.

The ACTFL's latest survey on the number of students taking foreign languages in grades K-12 in the US was conducted in 2007-2008. In that school year, there were 60,000 students studying Mandarin, an increase of 195 percent compared with the 2004-2005 survey, the highest jump of any language.

Shuhan C. Wang, director of the Chinese Early Language and Immersion Network (CELIN) at the Asia Society, estimated that the number is easily above 100,000 now, and counting students of Chinese heritage studying privately, about 300,000, she said.

"Chinese programs are growing," Wang told China Daily. "The field is growing. Because it's growing, we don't have a very good mechanism or money to collect data. All the data is outdated. The American council (ACTFL) data is the latest official data we have.

"In K-12, definitely over 100,000 students taking Chinese, not including Chinese heritage students," Wang said. "That's another 150,000 students. Their home language is Chinese. We have over 250,000 students taking Chinese in the country; over 300,000, including the universities."

Wang said the reasons for studying Chinese or other foreign languages are obvious.

"In order to compete in the global market, you can no longer compete with your neighboring state; instead, you need to compete with your neighboring country or any country in the world where the labor force is cheap - but good," she said. "Global competency has become a very important concept in education, although it has not been as prominent as what we would like to see for the 21st century, but it is coming up."

"Parents and students are looking at bilingualism, especially learning Chinese, as a ticket to future markets and jobs and as an asset for personal human capital," said Wang. "You use the target language, the buyer's language to open the conversation and the market, but you use English to close the deal. Use their language and culture to win their trust and to build relationships, and that's No 1 to opening the market," she said.

Wang's CELIN network, which started in 2012, numbers 150 schools and is growing. Thirty-seven of the immersion schools are in California; 26 are in Utah, a state that has an Asian-American population of only 2 percent.

Jon Huntsman lends a hand

"When Jon Huntsman [a Chinese speaker] was the governor there, he decided that Utah will develop students and a workforce that is proficient in world languages, mainly Chinese, French, and Spanish," explained Wang. "The goal was to establish dual-language immersion programs. Then the National Security Education Program established a Chinese Language flagship program to support the Utah initiative."

The Language Flagship sponsors Chinese programs at 11 US universities, which aim to provide undergraduates with "pathways to professional-level proficiency in Chinese alongside the academic major of their choice."

Yea-Fen Chen, director of the Chinese Flagship Program at Indiana University in Bloomington, said that students are studying Chinese at an earlier age, and she sees "a very high level of proficiency" in students by the time they reach college. The public schools in Monroe County, where Indiana University is located, just started offering Chinese.

Chinese is the most popular language at STARTALK, a federal program established in 2006 that supports summer programs for students and training for teachers in 11 "critical needs" languages. It is administered by the National Foreign Language Center at the University of Maryland. In 2014, STARTALK offered 55 Chinese programs for students and 40 for teachers, compared with 2007, when there were 18 for students and 17 for teachers.

"Now that China has opened up considerably for trade and tourism and has become more market-oriented, Americans find it fascinating culturally and historically," Catherine Ingold, director of the National Foreign Language Center and principal investigator for the STARTALK program, wrote to China Daily in an e-mail.

As the programs grow, so does the need for teachers. Chen said "we're not producing enough qualified teachers to meet the needs of students, especially K-12".

Said CELIN's Wang: "We still need a lot more teachers, and more effective teachers. The guest teachers from China, mostly brought here by an initiative under the College Board, have been able to fill this void.

"If we had more home-grown teachers, the quantity and quality of Chinese programs in the US would be greatly enhanced," Wang said. "The guest teachers are really good and bring in a fresh perspective and authentic Chinese culture. But they are restricted by policy that they can only stay here for up to three years. Most of them stay for one or two years, which is a lot of sacrifice on their part."

At the Asia Society, a NewYork-based educational organization founded by John D. Rockefeller III in 1956, Jeff Wang is the director of Chinese Language Initiatives and Education and oversees 100 pairs of sister schools in the US and China.

"We work with them to improve their Chinese language programs," he said of the schools. "Our goal is really to find a group of schools that have the potential to be exemplary programs for the region or for the country. The program needs to be good. Our biggest issue is teacher quality, instructor quality and effectiveness. We have about 300 teachers in our network; 90-plus percent of them are American-based teachers."

Confucius Classrooms

Also helping meet the demand for Chinese instruction is the Beijing-based Hanban, part of China's Ministry of Education. In the US, Hanban operates Confucius Institutes on 97 college campuses and runs 357 Confucius Classrooms in the K-12 category. Worldwide, those numbers are 443 and 648, respectively, according to Hanban's website.

"Schools are interested in offering Chinese because they do see some financial incentives from the Chinese government, funding Confucius Classrooms at the K-12 level," Abbott of ACTFL said.

Hanban's stated goals are: to make policies and development plans for promoting the Chinese language internationally; to support Chinese language programs at educational institutions of various types and levels in other countries; and to draft international Chinese teaching standards and develop and promote Chinese language teaching materials."

The US has the most Confucius programs by far. Those programs have run into some controversy in North America. Penn State University and the University of Chicago have dropped Confucius Institutes from their campuses, citing issues of academic freedom.

Wang looks at those situations more as "incidents of cultural communications breakdown" rather than rejection of the programs.

"The Chinese come in with their view of how things should be done, and not being familiar with how Americans do things, and vice-versa," she said. "I have visited numerous Confucius Institutes. Every Confucius Institute is different depending on what activities they propose to Hanban."

"Let it be fact-based," said Jeff Wang, on the disagreement between some Confucius Institutes and their hosts in the US. "If there are clauses in the agreement points in the arrangement of the collaboration that are inconsistent with the values and integrity of those institutions in the US, then they shouldbe reviewed and negotiated until satisfactory.Bring them out and you can negotiate that away."

"What I think is most important is engagement," he said. "By having a Chinese institution have a presence on an American campus, we should have confidence in the intelligence and critical thinking and skills of the American public, whether it's students or faculty of these truly great institutions. They're not easily persuaded one way or the other.

"Great institutions should be able to manage that influence much better than losing that benefit altogether. They're [the personnel coming from China to work with Confucius Institutes] also being influenced by Americans."

Wang said the value of the engagement outweighs the negatives that can arise between two different cultures.

Lui Huiquan contributed to this story.

Contact the writer at williamhennelly@chinadailyusa.com

(China Daily USA 11/28/2014 page20)

6 things you should know about Black Friday

6 things you should know about Black Friday

Calm comes to troubled Ferguson

Calm comes to troubled Ferguson

Daredevil dancer conquers mountain

Daredevil dancer conquers mountain

China's celebrity painters

China's celebrity painters

Beauty of Beijing float making debut in Macy's parade

Beauty of Beijing float making debut in Macy's parade

The plight of pregnant women in rural China

The plight of pregnant women in rural China

Rescue dogs show skills in NW China

Rescue dogs show skills in NW China

Top 10 largest hotel chains in China

Top 10 largest hotel chains in China

Most Viewed

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|

Today's Top News

China, US targeting terror online

More understandings, co-op between China and US

Macy's says huanying to Chinese tourists

Cupertino gets attention with its Asian-American-majority City Council

Amazon takes Black Friday to China

BMO Global Asset Management Launches ETFs in Hong Kong

BlueFocus aims to acquire Canadian company

Microsoft to face $137m bill for back taxes

US Weekly

|

|