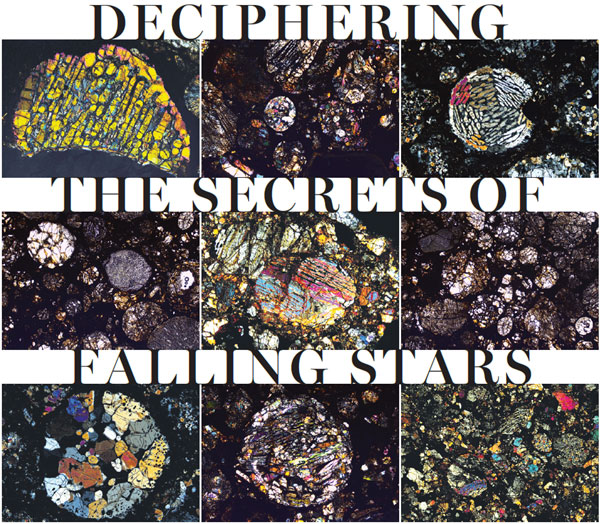

Deciphering the secrets of falling stars

Updated: 2015-08-20 07:08

By Yu Fei(China Daily USA)

|

||||||||

Scientist Lin Yangting collects meteorites, or 'pennies from heaven', to study

Lin Yangting has touched nearly 6,000 falling stars, or meteorites, and each tells a different story about the universe.

A researcher with the Institute of Geology and Geophysics, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Lin looks for tiny particles, thinner than one-tenth or even a hundredth of the width of a strand of hair, in the meteorites, which hide the big secrets of the solar system and the universe.

|

From top: Lin Yangting (middle) talks about a meteorite with his teammates; Lin Yangting in his laboratory, which is equipped with advanced nanoSIMS, an ion microprobe in CAS Institute of Geology and Geophysics. Photos Provided to China Daily |

How was the sun born? How did the planets, their moons, asteroids and comets form and evolve? How did life begin?

"Meteorites are like the bricks left over from building the mansion of the solar system," Lin says. "Some of them even contain the substances of the last generation of star or supernova."

"We extract the information they contain to trace the history of our solar system."

Falling stars on ice

Lin, 53, was born in a little town in southeast China's Fujian Province. He had a fascination with nature from a young age. He studied geochemistry at Zhejiang University, and then became a graduate student, majoring in cosmochemistry under Ouyang Ziyuan, an academician and the leading scientist of China's lunar exploration program.

The first meteorite Lin touched was the world's largest stone meteorite, which landed in northeast China's Jilin province in 1976. "When I touched it, I only felt a rock."

It was in the South Pole where Lin felt he was touching falling stars. Meteorites can fall anywhere. But in cold and dry Antarctica, they can be preserved for millions of years. Glacier movements concentrate meteorites in some places.

Collecting meteorites in Antarctica was Lin's dream for years. He took part in China's 22nd Antarctic scientific expedition in 2005. On the last day of that year, after studying meteorites for more than 20 years, Lin first picked up a meteorite on the glittering blue ice of Antarctica.

"In the lab, I only think about what information I can find in them, but in Antarctica, I really had the feeling of picking up falling stars," Lin says.

Risking bottomless crevasses, Lin and his teammates collected 5,354 meteorites during the expedition. He walked more than 20 km every day, and worked more than four hours back in the camp in the evening to weigh and record each of them.

During the expedition, Lin was excited to find a large meteorite, weighing 4.8 kg, and a little white meteorite, like a peanut. His teammates recall how he jumped like a child.

The little stone looked like a moon meteorite that Chinese scientists dream of finding. Among the 50,000 meteorites collected around the world, only about 140 are moon meteorites.

Returning from Antarctica, Lin found a gem cutting company to slice the meteorite. But lab tests showed it was from the asteroid Vesta rather than the moon. Although the Vesta meteorite is also precious, Lin was a little disappointed because Chinese scientists long for a moon meteorite to study before China can retrieve samples from the moon directly.

Pennies from heaven

Lin has also collected meteorites in the deserts of northwest China, and was once involved in a car crash during a sand storm.

But most of his work is done in the laboratory. Each meteorite is so precious that a piece as small as a grain of sand will be cut into many slices and analyzed with sophisticated equipment.

China has collected more than 10,000 meteorites from Antarctica. It took eight research teams three years to analyze almost 3,000 meteorites. More than 8,000 are still in cold storage.

"Sometimes it takes decades to study one meteorite, because of technological progress or new ideas," Lin says. "More than 200 students around the world have earned doctorates from research on a meteorite found in Mexico, which contains the refractory inclusion formed at the beginning of the solar system."

The research can be described as "pennies from heaven". "What attracts me most is there is always surprise. I never feel bored," Lin says.

At the end of last year, a research team led by Lin discovered organic matter in a piece of Martian meteorite, which was a promising indicator of life on Mars. The discovery was published in the professional journal Meteoritics & Planetary Science.

"At first we were looking for traces of water in it, and unexpectedly found carbon particles. That's rare," Lin says. "The accidental discoveries are amazing."

As China develops its deep space exploration, the Institute of Geology and Geophysics has set up the Key Laboratory of Earth and Planetary Physics, equipped with advanced NanoSIMS, an ion microprobe. "When I was a student, I had to go to Germany to do some experiments," Lin says. "But now German researchers come to our lab to do experiments."

His disadvantage is that he is always late in getting samples from other countries. "Actually scientists don't have much time to look for meteorites. Private meteorite collectors in other countries contribute a small quantity of samples to research organizations. But most Chinese collectors dream of making a fortune out of meteorites, and are reluctant to contribute even a little bit."

'Rabbit hole' on the moon

China's lunar exploration program and the planned Mars exploration have opened new fields of discovery in cosmochemistry in China.

Analyzing data sent back from Yutu, China's first moon rover, Lin's team found that a large volcanic eruption happened at the landing site, a basin called Mare Imbrium, about 2.5 billion years ago. Previously it was believed the moon had seen little geological activity since 3.1 billion years ago. They also found the thickness of the lunar regolith layer had been underestimated.

Their discoveries were recently published as a cover story in the US journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Where will Chang'e-4 and China's next lunar rover go? What's the scientific goal of the lunar probe? The China National Space Administration is seeking submissions, and some experts suggest exploring the far side of the moon where no human probe has landed.

Lin is curious about a mysterious tunnel on the moon, formed during the flow of lunar lava. When an asteroid hits the tunnel, it leaves a hole, dubbed a rabbit hole by some scientists. So far, four rabbit holes have been found on the near side of the moon, and one on the far side.

"If China's lunar rover could go down a rabbit hole - some are as large as a subway tunnel - it would be very challenging and interesting," Lin says.

China Features

(China Daily USA 08/20/2015 page9)

The changing looks of Beijing before V Day parade

The changing looks of Beijing before V Day parade

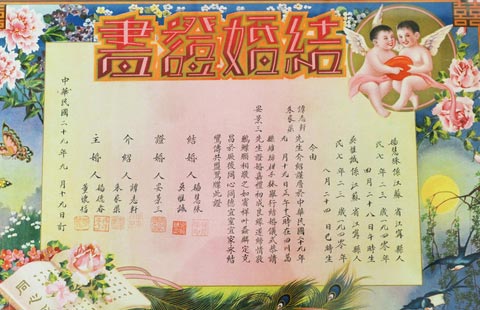

Nanjing displays ancient marriage, divorce certificates

Nanjing displays ancient marriage, divorce certificates

Top 10 Android app stores in China

Top 10 Android app stores in China

Ceremony held to mourn victims of Tianjin blasts

Ceremony held to mourn victims of Tianjin blasts

Silk Road city displays sculptures at exhibition

Silk Road city displays sculptures at exhibition

Top 10 companies with the most employees

Top 10 companies with the most employees

Men in Indonesia climb greased poles to win prizes

Men in Indonesia climb greased poles to win prizes

In pictures: Life near Tianjin blasts site

In pictures: Life near Tianjin blasts site

Most Viewed

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|

Today's Top News

Fitch warns insured losses from Tianjin explosions could reach $1.5b

Conflicting reports on possible Abe trip

Hillary Clinton breaks with Obama on Arctic oil drilling

At UN, China backs regional peace efforts

Man in yellow shirt is Bangkok bomber: Police

Beijing dismisses reports of Abe's China visit in September

Anti-corruption campaign 'good for China, US'

Police: Man in yellow shirt is Bangkok bomber

US Weekly

|

|