Wallace Chan: bringing stones to life

Updated: 2016-03-11 12:04

By Hezi Jiang in New York(China Daily USA)

|

||||||||

Guests flocked to the lobby of the Cooper Hewitt Design Museum on the Upper East Side of Manhattan on the evening of Jan 28, many wearing dazzling jewelry. One woman wore a gemstone-studded dress and a tiara.

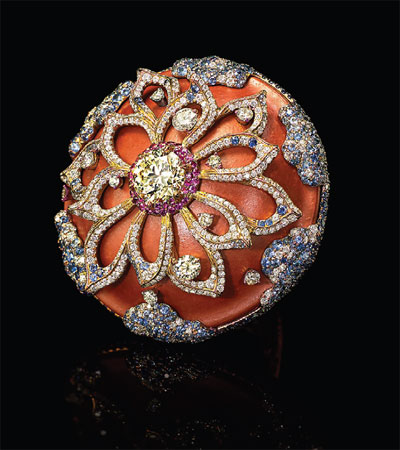

Most were drawn to an exhibit case displaying Wallace Chan's flower-shaped brooch Vividity - a 64-carat deep pink Elbaite tourmaline nested in a burst of rubies, colored diamonds and green tourmalines.

Wallace Chan was the first and only Asian designer ever invited to show at the Biennale des Antiquaires in Paris, the world's premiere haute jewelry exhibition. The Great Wall he presented there in 2012 - a necklace of antique Chinese imperial jadeite and diamond-encrusted maple leaves - sold for $60 million.

Chan's Heritage in Bloom, made with 11,551 diamonds and finished in 2015, was called the world's most expensive diamond necklace, according to The New York Times, and had a price tag of $200 million.

He is also the first Chinese jewelry artist ever invited to exhibit at TEFAF in Maastricht, Europe's most prestigious art fair, where he will present his jewelry creations, glass carvings and large-scale titanium sculptures from March 11-20.

On the wave of his growing international fame, Chan has brought his work to America for the first time. Along with the brooch, he announced the launch of a new book, Wallace Chan: Dream Light Water by Juliet de La Rochefoucauld that features 86 of Chan's 500 unique pieces.

"Wallace Chan's jewelry is like sculpture," said Keegan Goepfert, an art director with Les Enluminures gallery. "The object has such extraordinary presence and when you look at it closely, the choice and the setting of each individual stone is so technically and aesthetically amazing. The brooch itself on top of the stand moves, it's animate, it has a life."

Born in Fuzhou, Fujian province in 1956, Chan moved to Hong Kong with his family at the age of 5. They lived in poverty. Chan remembers that he would jump up to look into the windows of restaurants to see what people were eating. He wanted to know what restaurant food looked like.

"My childhood dreams were materialistic," he said. "I wanted meat, I wanted to have a chicken for New Year. I have a very humble background, and it makes me curious about everything."

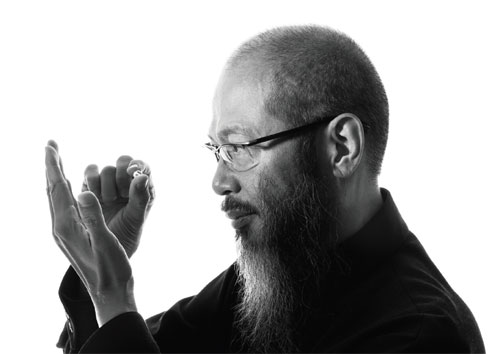

Now 60-years-old with a long salt-and-pepper beard, Chan in fact looks young for his age. His eyes are clear and smile a lot.

Wearing a plain black updated Mao-style suit, Chan wears no jewelry himself. "I like everything, so I can't decide what to wear," he said. "The jewelry I make is for the world, not for me. I am satisfied with these nice clothes."

Because of family hardships, Chan dropped out of school at 13, and his father sent him away to become a gemstone-carving apprentice.

"I was not happy with my work initially. I saw that other more experienced craftsmen were making beautiful shapes that I couldn't," said Chan. "After they went home, I would take their pieces and imitate the lines of their cuts for hours."

He often stayed at the workshop past midnight. Within three months, his work was outshining others who had been at it for years.

"I started to get into the inside world of gems," said Chan with a gesture of holding a knife. "You never know what the next layer is going to be like in a stone. When you carve jade, some green color or a crack might suddenly appear."

If the color does change, Chan's design immediately changes with it. If when carving a man a green color appeared, he would give the man a fishing pole leading to a green fish. If a color wasn't good in the face of a girl, he would put a hat or a floral wreath on her head.

"You have to follow the inside of each stone," said Chan. "Once, it took us eight months to make a white jade vase with the pattern of a hundred birds. We finished carving and our master worked on hollowing out the stone to make it a vase.

"Inside the stone he found a big piece of green jade, so without hesitating, we had to saw the vase apart to take out the green. The vase would have fetched $5,000, but the green jade was worth more like $150,000.

"You never know what's the most precious until the very end," said Chan.

To learn more about carving, Chan spent time in cemeteries, where he could study Western sculpture for free. He was fascinated by the way anatomy and muscles were portrayed and how they captured light and shadow.

In 1974, 17-year-old Chan founded his own workshop in Hong Kong. Now after 42 years, he has 16 people helping him develop new tools and polish stones, but he is still the one and only designer.

"Sometimes I have a dream of a design and I wake myself up and draw it," he said.

Once asked how many hours a week he worked, Chan responded, "When you love someone, do you say that you are in a relationship for three hours a day? If I only work according to a certain schedule, I would be like any other worker. I am in love. I'm forever in a romantic relationship with gems."

The cover of the new book features a special piece of his, The Wallace Cut, made with an "illusionary" carving technique combining cameo, intaglio and gem faceting.

"On the front, you can see five faces, but actually I only carved one face on the back of the stone," Chan told the audience at the museum. "The four more faces you see are actually the result of reflections that were created by precise calculations and faceting."

"It was reverse thinking combined with reverse carving motion," he explained. "What you see on the right I actually carved on the left and what you see that is deep inside the stone was actually carved shallowly."

It took Chan six months to develop the tools for the technique and two and a half years to master them. The whole process was done in water because it generated high heat that could damage the stone.

"As I was carving in water it meant I could not see the details so I carved stroke by stroke," he said, "taking it out of the water and checking to see it was okay then putting it back in the water to do another stroke.

"It was a long process but I entered a zone where my eyes, my heart and my hands were moving as one. Then I could carve in the water for two or three minutes without looking or checking."

Chan said he loves to experiment. He likes new technology and old tradition. He enjoys reading about physics, chemistry and philosophy.

Chan said that sometimes he will read a line in a book and sit there for a day to live between the words.

"I want my work to reflect my times. When people see a piece, they should be able to tell that it was made in 2016," said Chan. "I don't use 18K gold. I use titanium or porcelain. It makes the crafts more contemporary."

"I still dream. I dream about cutting the best gems. I dream about myself disappearing among the gems. I dream about if I was a gem, what would I look like? If a jeweler carves me into a beautiful shape, would I be hurt or would I be happy?" Chan said with a calm smile.

"A well-cut gem is more than a three-dimensional object. It has an inside too, that's another three dimensions. Same with humans. It takes time to know a gem, and it takes time to know a person," he said.

Chan has customers from the world over: China, the US, Switzerland, France and countries in Middle East. He tells all of his customers to take their time deciding on a purchase.

"I don't want them to buy it immediately after seeing the piece. I tell them to go back and if they miss it, if they still like it after three months, come back."

In 42 years, Chan has never opened a store. "I don't work for money, because then I have to listen to others. A store would constrain me," Chan said. "I don't do a brand either. I only do craft."

He has done 500 pieces in the past four decades, and has more than 1,000 works in progress.

"Painters use paint, musicians use notes, I use gemstones to create," he said. "Jewelry is the same as painting or music. It is a form of artistic expression. For more than four decades gemstones have been the most important language I use to communicate with nature and the universe. I use gemstones as my medium to create life and through creation, I become one with nature."

hezijiang@chinadailyusa.com

|

Portrait of Wallace Chan |

|

Gleams of Waves brooch |

|

The Mighty brooch |

|

Graceland ring |

|

Now and Always necklace produced with "Wallace Cut" carving technique. |

|

Secret Abyss necklace. Photos provided to China Daily |

|

Guests study Wallace Chan's Vividity brooch at Cooper Hewitt Design Museum on Jan 28. Hezi Jiang / China Daily |

(China Daily USA 03/11/2016 page11)

Beijing sees blue sky during the two sessions

Beijing sees blue sky during the two sessions

Fukushima five years on: Searching for loved ones

Fukushima five years on: Searching for loved ones

Robots ready to offer a helping hand

Robots ready to offer a helping hand

China to bulid another polar ship after Xuelong

China to bulid another polar ship after Xuelong

Top 10 economies where women hold senior roles

Top 10 economies where women hold senior roles

Cavers make rare finds in Guangxi expedition

Cavers make rare finds in Guangxi expedition

'Design Shanghai 2016' features world's top designs

'Design Shanghai 2016' features world's top designs

Cutting hair for Longtaitou Festival

Cutting hair for Longtaitou Festival

Most Viewed

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|

Today's Top News

What ends Jeb Bush's White House hopes

Investigation for Nicolas's campaign

Will US-ASEAN meeting be good for region?

Accentuate the positive in Sino-US relations

Dangerous games on peninsula will have no winner

National Art Museum showing 400 puppets in new exhibition

Finest Chinese porcelains expected to fetch over $28 million

Monkey portraits by Chinese ink painting masters

US Weekly

|

|