When PIGS fly, it's a hog's heaven

Updated: 2011-11-25 10:25

By Giles Chance (China Daily European Weekly)

|

|||||||||

China needs to be on the lookout for a multitude of opportunities as the dust settles in Europe

Over the past fortnight several events have occurred that make the likely outcome of the European financial crisis much clearer. It is now possible to speculate about how the post-crisis European landscape will look. In all of this there are several questions for China. Will it like the landscape that lies ahead and benefit accordingly? What are the likely threats and opportunities?

For the euro system to stay together, Germany and the European Central Bank need to issue and stand behind a large eurozone bond issue, in the amount of 2 trillion to 3 trillion euros. This amount could be supported by income to the European Central Bank derived from printing money at no cost to buy euro debt. It would finance the write-downs or "haircuts" suffered by European banks on their loans to Greece, Portugal, Ireland and Spain, allowing these countries to stay in the system. It would also finance the recapitalization of European banks to the tune of about 500 billion euros, and it would frighten market traders into liquidating their selling positions on the debt of the weaker euro countries.

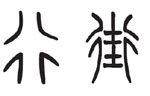

But issuing such a large eurozone debt contravenes the "no bailout" rule written into the European treaty. In addition, Germany has made it clear that it will not shoulder a large increase in eurozone debt that turns the over-spending of other European countries directly into a German problem. China and the other faster-growing surplus countries won't contemplate supporting the euro until the underlying euro structure is clearer. Moreover, 10 days or so ago, as the yield on Italian debt rose to more than 7 percent, it became clear that Italy, the world's third-largest borrower, is on the way to turning the PIGS - Portugal, Ireland, Greece and Spain - into the PIIGS. If Italy falls, even 3 trillion euros may not be enough to save the euro system. With GDP at about 9.2 trillion euros, and with about 5.4 trillion euros needing to be refinanced between this year and 2013, the chances of keeping the euro ship afloat do not look great.

Now we know for sure that there is no European safety net, and that it is every country for itself, we can start thinking about a partial breakup of the euro system. We can examine one by one the weaker euro countries, to find out which ones can stay in the euro, and which will have to go.

Greece will have to leave because, whatever austerity measures the government passes, Greek debt is too large ever to be repaid, and, as we are learning day by day, the likelihood of a Greek government forcing Greeks to transfer a high proportion of their country's GDP to repay debts is very low. Italy may also be unable to take the hard measures necessary to meet its debt obligations.

On the other hand, Portugal, Ireland and Spain have each shown themselves able to make tough decisions to cut spending. It is possible, but not certain, that these three countries can stay within the system.

The countries that leave the eurozone will have to reintroduce a national currency, which will devalue by up to 50 percent against the euro and other major currencies. This devaluation will increase their external debt by about 50 percent, and reduce the price of their domestic assets by about the same amount. Here lies the economic salvation for each country that abandons the euro, new capital starts to flow in to capture much cheaper assets, and exports boom as prices fall.

The immediate consequences of the PIIGS leaving the system are as follows: First, the ones who flee will suffer from a lack of spending power as their governments make deep spending cuts to restore or maintain credibility and their currencies devalue, making imports much more expensive. The countries that stay will be affected as they slash public spending, too. Second, Europe's banking system, with huge loans outstanding to the departing countries, will come under great stress. Third, the price of investment opportunities in the PIIGS countries will fall, making post-devaluation PIIGS assets highly attractive to investors with courage, determination and ready funds. Fourth, the euro, rid of its weakest members, will strengthen against other major currencies.

The French Prime Minister, Francois Fillon, against the background of a weaker outlook for the French economy, announced that France would increase its budget savings to 65 billion euros by 2016 to bring France's budget deficit down from 5.7 percent of GDP this year to within the euro limit of 3 percent in 2013.

France is rightly focused on retaining the AAA rating that enables it to access the capital markets and borrow on the best terms. This demonstration of French determination, which contrasts with Greek and Italian lack of discipline, is what may enable France to convince the markets and stay within the euro system. But Europe is still the largest destination for Chinese exports. Cuts in France, Italy and other European economies will reduce China's exports to Europe, and will have some negative effects on Chinese growth, although stronger demand from emerging markets such as India will partly make up for weaker demand from the developed world.

Among the countries in a position to benefit from bargains in the countries that leave the euro, China, with plenty of foreign currency ammunition available, is foremost. Flows of Chinese investment overseas last year rose year-on-year by 22 percent to $68 billion, bringing the total invested overseas by Chinese firms to more than $300 billion. But this is still a tiny amount for a $6 trillion economy.

The end of the European crisis could be the signal for much larger overseas investment flows from China. An increasing number of Chinese State-owned and private enterprises is anxious to enter foreign markets to expand and improve their businesses by winning market share from developed market competitors. Overseas investment presents China with the problem of finding qualified Chinese managers who speak English and other foreign languages, and who can navigate the waters of foreign cultures without drowning. At present, there are too few qualified managers for Chinese companies in China, let alone overseas. Chinese companies will need to rely on foreign managers to a much greater extent as they develop their businesses outside China. In turn, the integration of foreign managers will bring changes to the way that Chinese companies see and manage themselves.

Investment opportunities for China may also begin to emerge in the European banking sector as major banks, such as Commerzbank in Germany and Societe Generale and BNP Paribas in France, are forced to recognize large loan losses on investments to PIIGS governments, destroying their equity base. These banks and others will probably need to look beyond their own governments for recapitalization funds. There may be opportunities for Chinese investors to acquire substantial minority stakes in major European banks. HSBC has used its 20 percent investment in Bank of Communications in Shanghai to improve its understanding of the Chinese banking market and improve its own Chinese banking operations. In the same way as HSBC, the Chinese State-owned banks may be able to use investments in European banks to gain a better understanding of the European banking sector. In turn this understanding can inform and drive the development of their own banking businesses in Europe.

As a substantial portion of China's foreign reserves are invested in assets denominated in euros, a strengthening of the euro against other major currencies, particularly the US dollar, would be a welcome result from the crisis for China. Such a strengthening would be made possible by the disappearance from the euro system of the third-largest euro member, Italy, which with the other likely leavers Greece, Ireland, Spain and Portugal accounted for 35 percent of euro GDP last year. This would make a significant difference to the currency's credibility and valuation in the market. With Germany at its core, the euro would return to being the strongest currency among the world reserve currencies. The upward revaluation of the euro from current depressed levels could be considerable.

On balance, then, the euro crisis may present China with more opportunities than threats. But China must be ready to take advantage of these opportunities, not only by moving quickly to acquire important assets, but also by being able to manage them over the longer term.

The recent Group of 20 conference in Cannes showed that a further benefit for China of the crisis is the strengthening of the emerging market position relative to an over-indebted, undercapitalized developed world. In Cannes, China was able to discuss, once again, a move toward a new kind of world monetary system that does not depend on the US dollar as the core reserve currency. It is now clear that a new monetary order will emerge, but it will take some years to do so. The dollar's days as the world reserve currency are numbered.

In 2005, the US Federal Reserve chairman Ben Bernanke gave a key speech that introduced the idea of a savings glut in Asia that placed downward pressure on interest rates in the US Treasury market, and was responsible for the low yields that were driving increasingly risky behavior in the financial markets. Now that the Asian savings glut has come to the aid of the developed world, it is not so clear that saving is such a bad thing after all. Still, interest rates in China and elsewhere remain much too low to attract and retain money in savings accounts. Until interest rates rise significantly, we will continue to be threatened by a series of asset price bubbles, from real estate to precious metals and back again, as savings continue to seek investments that can offer a return. Until real interest rates rises on savings turn significantly positive, the possibility of financial crisis will remain.

The author is visiting professor at the Guanghua School of Business, Peking University. The views expressed in this article do not necessarily reflect those of China Daily.