First among rivals

Updated: 2011-11-18 07:47

By Andrew Moody (China Daily)

|

|||||||||

|

Bill Emmott says the China of 2050 will be incredibly different in unpredictable ways. Nick J B Moore / For China Daily |

Former editor of the economist points to china as top asian giant, but says US will not collapse

Bill Emmott, the respected author on Asian affairs, says the idea China is going to take over the world in the 21st Century is often overplayed.

"I think a world that is Sino-centric would not be comfortable for China as well. It would be a worry for many policymakers and thinkers in China," he says.

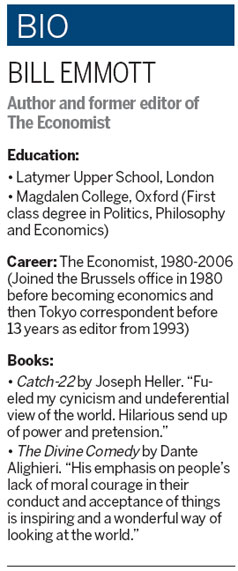

The 55-year-old former editor of The Economist, the current affairs magazine, and author of the highly-acclaimed book Rivals, which examines the interplay between Asian giants China, Japan and India, was taking morning coffee at The Arts Club in London's Mayfair.

The club, whose founders include Charles Dickens and whose recent guests have included Hollywood actress Gwyneth Paltrow, has been a regular haunt of artists and thinkers since it was formed in the 19th Century.

Emmott, who is convivial company and speaks in a calm precise manner, rejects the notion we are all going to become Chinese in the 21st Century and start speaking Mandarin, as espoused, to some extent, by fellow British author Martin Jacques in his book, When China Rules The World.

"I think China is going to be incredibly important and that it is going to be the single most important Asian country and one of two or three most important countries in the world. But more Chinese will be learning English than we Mandarin," he says.

|

"Martin rather treats China as a fixed entity going up the growth scale but not changing much internally in itself. But is that going to be true over 50 years or 100 years? The China of 2050 will be incredibly different in unpredictable ways to the China today."

Emmott, who divides his time between homes in Somerset in the southwest of England and London, is currently turning his attention toward Italy. He has just published a book, Forza, Italia: Come ripartire dopo Berlusconi, about Italy under Berlusconi and is about to make a film, which is to be given a cinema release in Italy and then shown on TV internationally.

Rivals, published in 2008, was one of few books about China among quite a plethora that have stood out in recent years.

The book examines the rivalry between China, India and Japan in a resurgent Asia but makes plain China is the potential giant of the three with an economy already two and a half times the size of India's.

"There was a good graph on The Economist's website recently looking at different measures as to how far behind India was compared to China and on virtually every one it was between 15 and 20 years behind," he says.

Emmott says one of the curious aspects of China and India's relationship is the little they know about each other.

"They are separated by the Himalayas, I guess, and culture, but what you find is that the Indians are a lot more conscious of the Chinese than the Chinese are of India. You find India specialists in China but you have to look hard," he says.

Emmott, who joined The Economist shortly after Oxford, where he took a first in Philosophy, Politics and Economics, was one of the magazine's most successful editors in its near-170-year history.

In his 13 years as editor, he more than doubled its circulation to 1.1 million copies and made it a leading current affairs publication in the United States also.

"At 1.1 million copies or 1.5 million copies (the current circulation) it really is a global brand whereas you can't be a global brand with 200,000 copies," he says.

He says working at the magazine was like being involved in some form of "Brains Trust".

"When I left what I realized was how much of the things that I knew and was knowledgeable about were actually things I had learned from my colleagues," he says.

Vacating the editor's chair in 2006, he has been unable to oversee the publication's coverage of the worst economic crisis since the 1930s.

"The word 'crisis' is wrong for something like this. A crisis ought to be something that happens quickly, a sudden surprise which then explodes. This is a long period of recuperation requiring a whole series of medical treatments," he says.

He believes the current problems will extend way into the decade but he does not expect China's recent economic success to go majorly off the rails.

"There is no reason to expect that. The local government situation (the debt highlighted earlier this year in China's National Audit Office report) is a sign of the magnitude of the stimulus program. That money had to go somewhere but it shouldn't collapse the economy," he says.

He thinks, however, the Chinese government's strategic aim to create a consumer society and be less reliant on being an exporter of cheap goods will be harder to achieve.

"There has been constant talk since even the 1970s about Japan rebalancing its economy toward being more consumption led but it has never actually happened. It still has a current account surplus, a strong export sector and a surplus of savings over investment. I suspect the same will be true of China," he says.

While China might have a difficult transition, the traditional media is in a fight for survival in the digital age.

Emmott believes the key to newspapers surviving is reaching a more targeted audience.

"I think many of them will survive but they will have to become more niche and clearly identify with a target readership. They can't be mass market general interest publications anymore," he says.

"I think the iPad is wonderful for The Economist and produces an experience for the reader which is very close to print so I think it can thrive either way."

As for the world economy, Emmott worries that some of the protectionist policies advocated in the US, particularly by the Tea Party Republicans, could plunge the global economy into a genuine depression.

"I think it would really become the worst financial crisis ever if globalization was stopped and capital and trade flow borders were closed. That was what happened in the 1930s," he says.

He does not expect the US to suddenly collapse as an economic power any time soon as Asia rises over the next century.

"This shift of power should not be seen as a decline of America. I would expect America to be back growing pretty rapidly over the next 10 years," he says.

Emmott says he will switch his own focus back to Asia after his current Italian diversion.

"I will return to Asia but in exactly what form I don't know. Asia has an irresistible attraction to me," he says.