Mars probe fuel 'not a threat'

Updated: 2011-11-18 06:54

By Xin Dingding (China Daily)

|

|||||||||

BEIJING - Toxic fuel in the Russian Phobos-Grunt spacecraft, stuck in Earth orbit, is unlikely to survive re-entry and endanger life, a space debris researcher said.

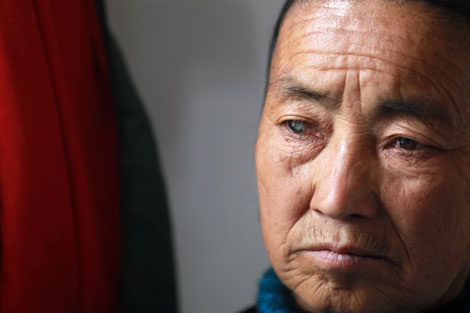

"The fuel inside the Russian Mars moon probe will have exploded as the probe breaks up during re-entry," said Han Zengyao, a researcher with the China Academy of Space Technology, who heads a team monitoring orbital debris.

|

The Russian probe, carrying China's first interplanetary satellite Yinghuo-1 to Mars, failed to fire two engines meant to boost it toward Mars after its launch on Nov 9. Ground control failed to establish contact and the probe's orbit is faltering.

Experts warned that the uncontrolled spacecraft could enter Earth's atmosphere in weeks. The fuel on board, accounting for roughly two-thirds of its 13 tons, could be a potential hazard if the craft crashes back to Earth.

The craft contains hydrazine fuel, which is highly corrosive and toxic.

Han believes that the probe will break up and explode dozens of kilometers above the Earth's surface due to aerodynamic forces and overheating.

"The liquid fuel carried by the spacecraft in a tank will explode in the aerodynamic heating and burn out. It is unlikely to survive and fall on Earth," he said.

Parts of the probe could still fall on Earth, though just how much is difficult to predict, he said.

The Yinghuo-1 probe, a 115-kilogram micro-satellite that accounts for only 1 percent of the total weight of the Phobos-Grunt mission, will be almost totally destroyed during re-entry, he added.

The Russian probe could be the third uncontrolled large object to fall back to Earth in recent months following the crash of a 5.6-ton US climate satellite into the Pacific Ocean on Sept 24 and the plunge into the Bay of Bengal of Germany's 2.4-ton Rosat space telescope satellite on Oct 23.

"As more spacecraft are sent into space, more objects will re-enter Earth's atmosphere. In fact, trackable space debris with a diameter of more than 10 cm returns to Earth's atmosphere every day but only a few of these objects actually hit the Earth," he said.

Orbital debris includes derelict spacecraft. NASA said more than 20,000 objects larger than 10 cm are known to exist.

The debris poses a threat to functioning spacecraft. Even debris just 1 millimeter in size could travel at an average speed of 10 km per second, 10 times faster than a bullet and easily penetrate a spacecraft without protection, he said.

Some debris will take centuries to decay.

Usually, the higher the altitude the longer the debris will remain in Earth orbit. Debris left in orbits below 600 km normally falls back to Earth within several years.

Retired in 2005, the US climate satellite, in a 578-km orbit, took six years to re-enter the Earth's atmosphere, while Germany's Rosat satellite, circling in a 585-km orbit, retired in 1999 and took 12 years to fall back to Earth.

As for space junk at altitudes of 800 km, where the greatest concentrations of debris are found, the time for orbital decay is often measured in decades. Above 1,000 km, orbital debris will normally continue circling the Earth for a century or more.

Experts warned that once a "critical density" of space debris is reached, a process called collisional cascading (or chain reaction) - collision fragments will trigger further collisions - would start, around the year 2050. Consequently, the Earth could be covered by a cloud of debris too dense to allow any satellites.

"This is a concern shared by space-faring countries, including China, and efforts must be made together to control the growth of space debris," he said.

With a growing space presence - 20 satellites launched in 2010 and at least 20 space launches planned this year - China is doing its share to take measures to tackle the problem, he said.

The government has allocated special funds to examine space debris, set up models and envision possible scenarios, he said.

China, for instance, has ensured that any remaining fuel in derelict orbiting launch vehicles has been vented out to avoid explosions and their orbits have been lowered to allow them to re-enter sooner, he said.

Since 2000, no upper stages of launch vehicles from China have exploded in space, he said.

In orbit 35,786 km above the Earth's surface, where communication satellites are positioned, China has elevated the altitudes of its three defunct satellites to spare precious resources and avoid interrupting other communication satellites in orbit, he said.

As for low Earth orbits, where debris concentrates, satellite designers are researching measures to prevent derelict satellites from exploding, including cutting circuits on board and venting out remaining fuel and gas, he said.

China also realizes that cleaning up space debris is, and will be, a major issue.

In a program funded by the government, researchers are doing concept studies of "space tugs" to pull retired satellites out of orbit, he added.