Ruling flawed on jurisdiction grounds

Updated: 2016-07-20 08:53

By WANG JUNMIN(China Daily)

|

||||||||

|

|

Photo taken on July 17, 2016 shows a deepwater fish farming base near Meiji Reef of the Nansha Islands of China. Since fishery expert Lin Zailiang started a fish farm in Meiji Reef of South China Sea nine years ago, the deepwater fish farming cages have increased to 62 by now. Rare commercial fish cultured here are sold well both home and abroad. [Photo/Xinhua] |

The Philippines, the United States, Japan and Vietnam have demanded that China abide by the arbitral tribunal's ruling on a case initiated by the Philippines against China over the South China Sea dispute to avoid violating international law.

Apparently, the arbitral proceedings were based on the articles of Annex VII of the United Nations Convention of the Law of the Sea. But the tribunal committed mistakes in the identification of the South China Sea dispute between Beijing and Manila and applying its legal provisions. Since the tribunal has no jurisdiction over the case, its ruling was bound to be null and void.

Whether China's maritime entitlements in the South China Sea are beyond the scope of UNCLOS, two facts can answer this. First, UNCLOS is a charter to regulate the international maritime order but does not regulate all international maritime issues. In its introduction, UNCLOS admits it cannot handle all maritime issues and emphasizes that issues not stipulated by it should be dealt with in accordance with the rules and principles of general international laws. For example, UNCLOS has no provision on the baseline of the territorial seas of a country's islands far out in the sea.

On a country's historic titles, too, it does not contain specific clauses, but it accepts the status of these rights in international law and views them as exclusions to the application of its rules. This testifies Manila and the tribunal cannot deny Beijing's maritime rights not mentioned but recognized by UNCLOS.

Second, according to international law, UNCLOS has no retrospective effect. So when UNCLOS stipulates such features as low-tide elevations, reefs and shoals cannot be regarded as territory, it does not mean these features were not part of a country's territory before it took effect on Nov 16, 1994. In fact, long before UNCLOS came into effect, China had designated Nansha Islands as an integral entity and laid claim to and exercised sovereignty over its islands, reefs, atolls and shoals.

In the arbitral case, when mentioning China's "historic titles" in the South China Sea, the Philippines argued that Beijing does not lay claim to its "historic sovereignty". It is well known that a country's "historic titles" in the sea according to international law refer to its rights over the waters it has enjoyed since ancient times, which include "historic sovereignty" and "non-exclusive historic rights."

On China's law on its exclusive economic zone and continental shelf, its foreign ministry spokespersons and scholars only put forward Beijing's "historic titles" in the South China Sea. But that does not mean China has abandoned its "historic sovereignty" in the sea.

In the case, Manila also divided Nansha Islands into different parts and only demanded that the tribunal rule on the maritime rights of islands and reefs "occupied or controlled" by Beijing, deliberately shunning other islands and reefs of Nansha Islands, including the ones illegally occupied and claimed by it. In so doing, the Philippines tried to disavow China's sovereignty over Nansha Islands in its entirety, deny its illegal occupation and claim over some of Nansha Islands' islets and reefs and the fact that they form an archipelago.

In its ruling, the arbitral tribunal disregarded the archipelago status of Nansha Islands and China's "historic sovereignty" of its waters and denied China's maritime rights over Nansha Islands. Therefore, its ruling has no binding force.

Also, Manila didn't demand the tribunal to rule on its territorial and sovereign disputes with Beijing, but their maritime dispute in the South China Sea involves their maritime demarcation and China's "historic sovereignty".

On Aug 25, 2006, China made it clear in a document submitted to the UN secretary-general that it would not accept any dispute settlement procedures involving, among other issues, the demarcation of sea waters, the ownership of historic bays, and military and law enforcement activities.

Since China's disputes with its neighbors in the South China Sea involve territorial sovereignty, maritime demarcation and historic sovereignty over Nansha Islands, they cannot be settled through compulsory arbitration procedures stipulated by UNCLOS. Therefore, the arbitral tribunal has no jurisdiction over the Beijing-Manila dispute and its ruling is thus flawed.

The author is a research fellow with the Party School of the CPC Central Committee.

Taiwan bus fire: Tour turns into sad tragedy

Taiwan bus fire: Tour turns into sad tragedy

Athletes ready to shine anew in Rio Olympics

Athletes ready to shine anew in Rio Olympics

Jet ski or water parasailing, which will you choose?

Jet ski or water parasailing, which will you choose?

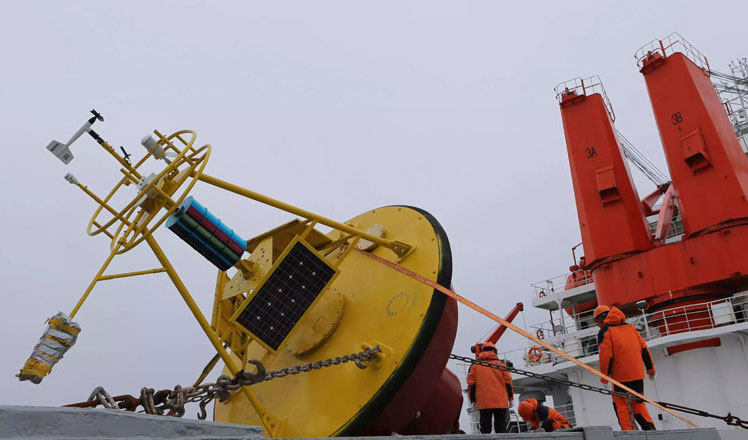

Icebreaker Xuelong arrives at North Pacific Ocean

Icebreaker Xuelong arrives at North Pacific Ocean

Tourists visit Yehliu Geopark in New Taipei

Tourists visit Yehliu Geopark in New Taipei

Uphill battle for cyclists in downhill race in Zhangjiajie

Uphill battle for cyclists in downhill race in Zhangjiajie

Shennongjia added to World Heritage List

Shennongjia added to World Heritage List

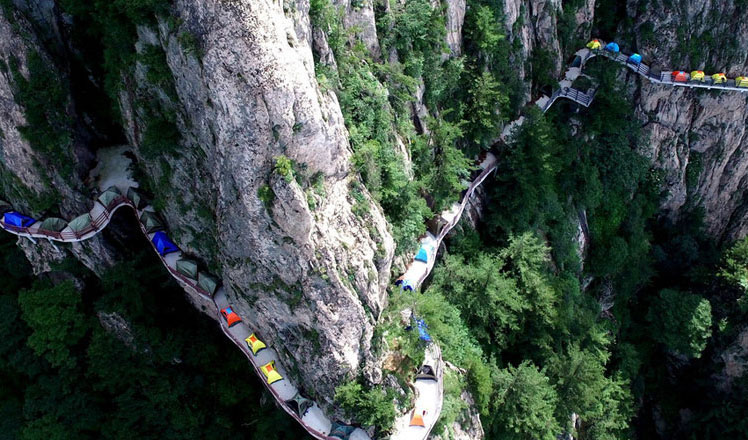

Campers sleep perched on cliff face in Central China

Campers sleep perched on cliff face in Central China

Most Viewed

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|

Today's Top News

Ministry slams US-Korean THAAD deployment

Two police officers shot at protest in Dallas

Abe's blame game reveals his policies failing to get results

Ending wildlife trafficking must be policy priority in Asia

Effects of supply-side reform take time to be seen

Chinese State Councilor Yang Jiechi to meet Kerry

Chinese stocks surge on back of MSCI rumors

Liang avoids jail in shooting death

US Weekly

|

|