A swampy walk on the wild side

Updated: 2013-11-10 08:03

By Anna Bahney (China Daily)

|

||||||||

|

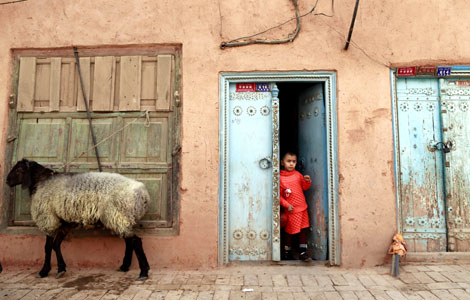

The swamp walk in the Big Cypress National Preserve provides a real connection and overall experience of the Everglades. Photos Provided to China Daily |

Spiders, snakes, alligators and the occasional panthers make this tourist trek through Florida's Everglades wetlands an unforgettable intimate encounter with nature, Anna Bahney reports.

The immense cypress tree at mile marker 54.5 of the Tamiami Trail - the highway that cuts across the Everglades in southern Florida - looks like it belongs in a fairytale. Draped in robes of Spanish moss, the tree stands above its mirror image, reflected in a pond.

But follow the path beyond the trail, and the water becomes a murky swamp crawling with formidable spiders, a variety of snakes, congregations of alligators and, occasionally, panthers. What counts for land there yields apples that taste like turpentine and strangler figs that compete so fiercely for light under the forest canopy they sometimes subsume the host tree their branches embrace.

This foreboding world would seem the least appealing of the natural riches in Florida, where white-sand beaches line an immense coastline. Yet every year, tourists venture beyond that cypress to experience one of the most intimate encounters with nature that you can find: a swamp walk.

There's no airboat here. No kayak. No boardwalk. Just old shoes, a walking stick and mucky brown swamp water rising, at times, up to your thighs.

Sure there are risks to walking through a swamp - of running into gators or panthers or, more likely, of tripping over cypress knees and touching poison ivy. But facing all these fears, as you troll at a step-by-careful-step walking pace through a swamp canal, accomplishes something a visit to Margaritaville won't.

It shuts everything else off, save the sound of your feet squishing through mud. As you walk, you're not thinking about who is texting you or whether your maps application will steer you to a decent place to have dinner. You're considering that hawk soaring above you, the sound of tree frogs croaking and, most importantly, what that thing is that's touching your leg right now.

"It forces you to slow down," says Clyde Butcher, a landscape photographer whose gallery, Big Cypress, is on the trail near that tree. He started leading swamp walks on his 5 hectares within the Big Cypress National Preserve 20 years ago. "Folks say they've seen the Everglades, but after they walk the water they say, 'That was the first time I had a real connection'."

While indigenous people like the Seminoles have been walking in the swamps for generations to find refuge from settlers and armies, and hunters have walked the swamp to capture rare animals, birds or plants, tourists have taken up walking the swamp for sheer entertainment only during the past 20 years. The swampland's addition to the tourist circuit has occurred gradually, coinciding with a renewed interest in Everglades conservation.

"It is a paradigm shift as we recognize it is best not to drain these areas, but to leave them, restore them and explore them," said Bob DeGross, chief interpreter at Big Cypress National Preserve, which leads its own swamp walks.

That perspective is a departure from the approach taken nearly 150 years ago, when a report exploring the feasibility of draining the swamp for productive agricultural and development use concluded that the Everglades were "suitable only for the haunt of noxious vermin or the resort of pestilent reptiles".

So in addition to Big Cypress National Preserve, parks like the Fakahatchee Strand Preserve State Park and the Everglades National Park offer ranger-led walks. But when I went to Big Cypress last spring, I opted for a walk given by the staff at Clyde Butcher's gallery. He offers guided wet walks from October through March. Walks are typically suspended during the late spring and summer because of alligator mating as well as the rainy season and its attendant lightning.

I hoped that instead of an educational foray, I'd get an impressionistic tour, one somehow suffused with the aesthetic of Butcher's sublime large-format photographs of the swamp.

Our guide ended up being Brian Call, an even-toned and laidback nature photographer, who offered two rules before entering the swamp. No 1: Keep your walking stick in front of you. The water is surprisingly clear, but with 10 people slogging through, it can become murky, hiding tree roots and "other things", on which he did not elaborate. No 2: Keep your hands off the trees. The air plants, or epiphytes like some ferns, orchids and bromeliads that grow non-parasitically on the trees, are touchy about being touched. Plus, he added, there are spiders. So much for purely aesthetic appreciation.

Our group was made up mainly of people in their 50s and 60s, including my in-laws, both snowbirds.

We all spent our nervous energy snapping photos of alligators around the pond next to the parking lot and fussing about which pants and shoes to wear. But as we headed onto the muddy trail, our nerves were oddly subdued by the first sighting that Call pointed out: An alligator. A few of her babies. And a large male alligator next to her. We all eyed one another, perfectly silent, as the alligators dipped in and out of the water. Heart-pounding panic had no place in this setting. There was only wonder.

After we slogged along the trail awhile, it was time to dip in. It wasn't easy to plunk my first foot in the dark, cool water, beetles skimming the surface, feeling around for a bottom you can't see. As I descended, air bubbles scattered over my leg beneath my pants. "What is that?" I briefly wondered, shivering.

Tree roots startled me as they brushed against my ankles, and when I stepped on them they were so slippery that I had to cling tightly to my walking stick. I was closely trailing my mother-in-law, who was closely trailing Call. The procession came to a stop when we saw a great egret perched above the water.

That wasn't the only surprise we'd encounter. When we moved into the "prairie", an area of the swamp with long, yellow saw grass and dwarf cypress trees instead of vegetation that would supply a thick canopy overhead, we realized that much of the water had evaporated. That meant that the area was more muddy than swampy. But over the summer, the alligators' eggs hatch, and the rain swells the swamp in time for the fall season.

On our walk, a spectacular highlight came from a different sort of sighting: Our guide, Call, came to a stop, saying, "Look!". We turned, expecting a gator or a snake. "That pattern of light on the cypress makes a great picture," he said.

I dutifully raised my camera to take the shot and moved on. It was only when I got home that I realized that this photo - singular among a camera card full of hurried shots of alligator eyes and my mother-in-law's pant legs - captured the sublime and slow quiet I was looking for. Though it wasn't a Clyde Butcher original, it was maybe better: it was mine.

The New York Times

Post-baby Duchess

Post-baby Duchess

Victoria Beckham S/S 2014 presented during NYFW

Victoria Beckham S/S 2014 presented during NYFW

'Despicable' minions upset Depp's 'Lone Ranger' at box office

'Despicable' minions upset Depp's 'Lone Ranger' at box office

'Taken 2' grabs movie box office crown

'Taken 2' grabs movie box office crown

Rihanna's 'Diamonds' tops UK pop chart

Rihanna's 'Diamonds' tops UK pop chart

Fans get look at vintage Rolling Stones

Fans get look at vintage Rolling Stones

Celebrities attend Power of Women event

Celebrities attend Power of Women event

Ang Lee breaks 'every rule' to make unlikely new Life of Pi film

Ang Lee breaks 'every rule' to make unlikely new Life of Pi film

Most Viewed

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|

Today's Top News

World powers, Iran to hold news nuclear talks

CPC session begins to set reform agenda

Economic growth to continue

US Oct jobless report paints dim picture

Obama's approval rating plunges to 41%

China's discipline agency targets holiday luxuries

Chinese land reform at crucial stage

Senior official at Cosco under investigation

US Weekly

|

|