Voices for change

Updated: 2011-11-19 07:46

By Pauline D. Loh (China Daily)

|

|||||||||

|

Alice Waters and Dai Jianjun swap stories at the panel discussion on food at the US-China Forum on the Arts and Culture. Photos by Feng Yongbin / China Daily |

|

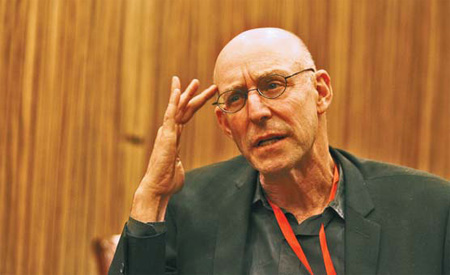

American writer and food activist Michael Pollan makes his point. |

|

|

Three vocal Americans and three equally articulate Chinese shared the stage and debated issues ranging from food safety to how consumers can influence government policies. Pauline D. Loh reports.

They are the leading voices in the push for healthier eating and organic food in the United States. Next to them are seated three Chinese, two ladies and a gentleman. The Chinese faces are less known, but more than hold their own in this cross-cultural discussion on food that throws up more similarities than differences.

It is Friday and the first program on the second day of the US-China Forum on the Arts and Culture. "Food as Culture: Attitudes on Food and Sustainability" features panelists Alice Waters and Michael Pollan from the US; and Zhang Yinghui, Dai Jianjun and Shi Yan from China. Orville Schell plays moderator and shows off his bilingual skills.

While Waters and Pollan are already well known to the gathered foodies, we are curious about the Chinese faces. The publicity material describes them as food activists - a term that conjures up images of placard waving protestors.

The first to be introduced is Zhang, a former editor and mother of two who started an Internet column about an organic lifestyle after she discovered food on the table was no longer what it seemed. Sometimes knowledge is dangerous and Zhang got so scared by what she found out that she no longer ate at restaurants and instead began hunting for sources of safe meat and vegetables.

In that she was traveling a parallel path with Pollan, who also got curious about the food he was eating and where it was coming from, although his journey started as journalistic curiosity and she was merely shopping to protect her family's well-being.

Zhang decided to share her knowledge online with friends, and started organizing a farmer's market as well as healthy, organic school dinners as a natural progression of her networking.

Pollan agrees that food safety is an important driver in the organic, green movement.

"Our food safety has changed more in the last 100 years than in the last 4,000 years. In China, it has changed much in the last 30 years. The food chain has grown longer. Farmers no longer know who they are selling to and when that happens, they cut corners."

Pollan describes how one of his first assignments as a journalist was to a potato farm in Idaho that used so much pesticide the farmer was afraid to go into his fields. Everything was automated from his garage.

Dai Jianjun, the farmer-restaurateur from Hangzhou, says the only way to retain taste in food is to respect and keep traditional ways of agriculture.

"It used to be that a pig on the farm would eat up all the scraps. There would be nothing left. A farmer told me once that in the city, meat doesn't taste like meat. Vegetables do not taste like vegetables," Dai says, adding tongue-in-cheek. "That's why men who eat these products don't have a man flavor."

It is the first of many comments from the straight-talking Hangzhou entrepreneur that cracks the audience up. But he makes his point.

For Shi Yan, the co-founder of organic cooperative Little Donkey Farm, the green movement in China started 10 years ago when a group of young visionaries saw what was coming. They petitioned the government to give them land and a grant to start the organic farm.

But Shi says the bicultural exchange on food between China and the US is actually a 100-year-old story. In 1911, an agriculture scholar came to China to ponder a question that still fascinates some Americans: How has China kept its land fertile and productive for 4,000 years?

For Alice Waters, it's the threat of fast food and mass producers that started in the 1950s that most concerns her. The "fast, easy and cheap" products totally indoctrinated Americans, with candy from vending machines, fizzy soft drinks, hamburgers, hotdogs and pizzas.

The threats have grown and overwhelmed ethnic and native cuisines and become the US' most notorious exports.

But Pollan offers solace with this advice: The role of the consumer is very powerful. You can refuse to eat fast food. You can demand truly organic produce, and you can vote with your fork and chopsticks to influence the government to better regulate agriculture and food safety.