Expanding large classroom study of China

Updated: 2014-05-30 06:26

By QIDONG ZHANG in San Francisco (China Daily USA)

|

||||||||

|

|

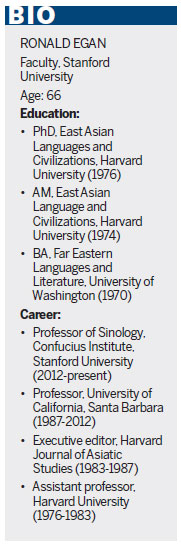

Ronald Egan. Stanford University Faculty, who teaches a general education undergraduate class on Chinese literature and history. Qidong Zhang / China Daily |

In Ronald Egan's general education undergraduate class on Chinese literature and history at Stanford University, he likes to ask his students to raise their hands if they have ever heard of or read the Chinese Qing Dynasty classic novel Dream of the Red Mansion.

"Usually there is none from among the American students. So I tell them it's better that they learn of it now than later. And I also tell them that they are going to enter a world that they don't even know exists. And they will find this world absolutely fascinating and thrilling," said Egan.

A sinologist specializing in Tang poetry and Song dynasty lyrics, Egan is in his second year of teaching Chinese literature and history at Stanford's East Asian language and culture department, after 25 years of teaching at the University of California at Santa Barbara (UCSB) and eight years at Harvard.

"I like to think of myself as a faculty member at Stanford fulfilling an important role in introducing Chinese culture and tradition to American students who do not know about it," said Egan.

Egan's interest in China developed "accidentally" at 19, when he took a general Chinese language class "for fun" as a sophomore at UCSB, having no idea what he was going to learn.

Originally intending to major in English literature, his professor at the class changed his destiny. That professor was Kenneth Hsien-yung Pai, a writer who has been described as a "melancholy pioneer" in Chinese literature, and is appreciated for sophisticated narratives that introduce controversial and groundbreaking perspectives in Chinese literature.

He was also known for his efforts to save kunqu, one of the oldest extant forms of Chinese opera from the 16th to the 18th centuries and getting it listed as a masterpiece of Oral and Intangible Heritage of Humanity by UNESCO in 2001.

"I only realized years later who my teacher was," Egan said. "He was very good to me, very encouraging, and taught me to love Tang poetry and Song lyrics, among the most influential components of Chinese literature and history.

"He also took me back to Taiwan when I was a senior, found me a family to live with and a tutor to teach me Mandarin. That really changed my life path, and it was my great good fortune to encounter such a person."

Growing up in Connecticut in a musical family, Egan had no prior exposure to Chinese language and culture. After exhausting all available courses at UCSB, he transferred to University of Washington in Seattle to study under Hellmut Wilhelm, an internationally acclaimed scholar of Chinese history, literature and philosophy. Wilhelm's father Richard was a missionary in Shandong in 1920s and the first translator of the I Ching, one of the oldest Chinese classical texts.

Egan attributes his flawless Mandarin to the two years he spent living with a Chinese family during his studies in Seattle. Isabella Yen, who was in charge of the Chinese program at the university, was the granddaughter of Yan Fu (1854-1921), a Chinese scholar and translator most famous for introducing Western ideas, including Darwin's "natural selection", to China in the late 19th century.

Egan continued his doctoral studies at Harvard in 1976 and started his teaching career there, before going to UCSB and Stanford.

After publishing The Literary Works of Ouyang Hsiu (2009) and Word, Image and Deed in the Life of Su Shi (1994), his most recent book was The Burden of Female Talent: The Poet Li Qingzhao and Her History in China (2013), which received wide attention from scholars.

"The book on Li Qingzhao is an attempt to provide a new interpretation on this extremely gifted Chinese female poet whose actual talent has been distorted by the tradition which insists on viewing her as a devoted wife, and a forlorn widow after her husband died," said Egan.

Li was actually extremely competitive and ambitious, vying with her fellow male poets and eager to prove herself.

Egan also takes up the controversial argument among Chinese scholars as to whether she re-married or not. Egan believes that Li not only remarried, but also divorced her second husband only 100 days after the wedding. She was put into jail for filing a lawsuit against him for corruption, something no woman was allowed to do at the time.

"It was considered a disgrace in ancient Chinese society for a woman to re-marry, let along the fact that she initiated divorcing her husband and filing a law suit against him and was put in jail. That was how the big dispute began on her being such a great poet, but also a ‘disgraced' woman."

Egan's academic path also had another fortunate encounter with Qian Zhongshu (1910-1998), a highly acclaimed Chinese writer best known for his satirical novel Fortress Besieged.

"I met him in 1979 right after the Cultural Revolution. He came to lecture at Harvard and I talked to him about his scholarly interest in traditional Chinese literature," Egan said.

Stimulated by Qian's works, Egan translated his Guanzhui Bian - Limited Views: Essays on Ideas and Letters. This translation of 65 essays makes available for the first time in English a representative selection from Qian's massive four-volume collection of essays and reading notes on the classics of early Chinese literature.

Going to China several times a year to attend conferences, give lectures and meet with scholars, Egan said there is much more communication between scholars in his field now and the academic environment is encouraging. He said he would, however, love to see more American students having graduate-level interests in China studies to balance things out.

"Americans in general are incredibly ignorant about China," Egan said. "If you talk to American college students, they mostly know nothing about Chinese history, culture and literature.

"In contrast, if you initiate any conversation with Chinese students, they have at least 10 times more knowledge about Western culture, literature, history, and that is really a shame. I take my undergrad teaching very seriously and believe the top priority today is to expand large classroom teaching at universities about Chinese language, history and literature," said Egan.

kellyzhang@chinadailyusa.com

Chinese Navy leave Pearl Harbor to join RIMPAC drill

Chinese Navy leave Pearl Harbor to join RIMPAC drill

'Cracking Tech Fortune Cookies'

'Cracking Tech Fortune Cookies'

US, China keen on fixing ties

US, China keen on fixing ties

Traditional Chinese medicine enlivens RIMPAC crowd

Traditional Chinese medicine enlivens RIMPAC crowd

Hainan provides limo service in Seattle

Hainan provides limo service in Seattle

Wanda's Chicago deal is first in US realty

Wanda's Chicago deal is first in US realty

Insurer's office to serve Chinese community

Insurer's office to serve Chinese community

Xi gives speech at SED opening ceremony

Xi gives speech at SED opening ceremony

Most Viewed

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|

Today's Top News

Chinese are No 1 buyers of US residential property

College addresses need for experts in anti-terrorism

China-US investment treaty on fast track

Minister: US 'key' to global recovery

Snowden applies for asylum extension in Russia

5 killed in Houston shooting, standoff underway

Xi: World big enough for two great nations

China, US unite against illegal wildlife trafficking

US Weekly

|

|