Backtracking to know Chinese community

Updated: 2014-08-01 11:52

By Amy He in New York(China Daily USA)

|

||||||||

As a Columbia University graduate student and activist in the 1970s, Peter Kwong felt he didn't have a true understanding of Chinatown and the Chinese community at large. So he backtracked.

|

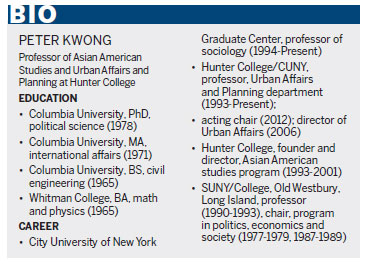

Peter Kwong is the founder of the Asian American Studies and Urban Affairs and Planning at Hunter College in New York. Provided to China Daily |

He went back to the 1930s to learn more about how the Chinese community lived and how the Great Depression affected Chinese. And he went back to review the impact WWII had on the community and its views on politics at the time.

What Kwong, who has been teaching Asian-American studies at Hunter College in New York City since 1993, found was that the Chinese were politically active, something he said is not discussed much today.

"I tried to understand what was happening. The Chinese were very active politically. It's just that most of the mainstream did not understand, because they were only narrowly looking at the voting population, which parties they voted for, and whether they could vote or not," he said.

Through his research, Kwong had found that the Chinese in the US were very vocal about the war against Japanese invasion in China, and that they supported China monetarily and spiritually, donating millions of dollars. Chinese urged Americans to boycott products that came from Japan, he said, adding that the Chinese community also lobbied Congress and got movie stars involved, demonstrating on Fifth Avenue and beyond.

"There were all these levels of complex political perspectives at play. The Chinese were very much - even though they were in Chinatown, in supposedly isolated ethnic communities - a part of, and very much involved in, domestic American politics, domestic politics in China, as well as the international movement," he said.

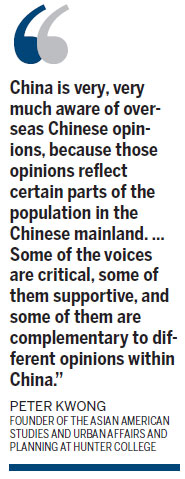

More significantly, Kwong said he found that the Chinese community's involvement had such a major impact on the government in the Chinese mainland that it began to recognize the importance of support from overseas Chinese.

Kwong found that Chinese living outside of China were more influential than a lot of people gave them credit for: "China is very, very much aware of overseas Chinese opinions, because those opinions reflect certain parts of the population in the Chinese mainland. Some of the voices are critical, some of them supportive, and some of them are complementary to different opinions within China."

The history of the Chinese community in the 1930s and 1950s was the subject of Kwong's graduate school thesis at Columbia University, and which was later turned into his 2001 book, Chinatown, New York: Labor and Politics, 1930-1950.

Born in Chongqing, China, Kwong and his family moved to Shanghai, and later to Taiwan where he grew up, before coming to the US. Kwong lives in the Manhattan section of Tribeca with his wife and Chinese historian Dusanka Miscevic, with whom he co-wrote Chinese Americans: An Immigrant Experience.

Living in the Empire State since the 1970s, Kwong said he has seen how activism and political participation in the Chinese community have changed through the decades. While the Chinese in the US were active in the period leading up to and during WWII, the Chinese living in America now and in the recent past have not been as active as their prior generations.

People organize differently and being active in American politics now requires a different kind of community action, he said. The first hurdle is just getting Chinese to participate in local government at all, he said, adding that their involvement has certainly picked up, with more Asian representatives in American government than ever.

But the effort to get representation has been just that, getting representation without touching on deeper community issues, Kwong said.

"Those who participate in American electoral politics and non-profits tend to be English-speaking and have limited access to the community. So a lot of times, the community has issues that are not being voiced by these members," he said. "American politicians often find that if you want to navigate within the Chinese community politically, you have so many different issues that the safest way to go about it is to be very, very general."

There is a lot of pride within the Chinese community, he said, so it wants to feel proud that it has elected politicians who share a common cultural background. But that often means that ethnic solidarity becomes the "overwhelming message" of any Chinese or Chinese-American politician looking to run for office, with little regard for other concerns, he explained.

"In the old days, you get elected by delivering services, and sometimes you get into very controversial issues," he said. "But by and large, this is a reflection of the pattern of American politics as well, where campaigning is basically offending the least number of people. Once you get elected, you don't really have a mandate for doing anything."

Kwong remains active in the local Chinese community, working with the Asian American Legal Defense and Education Fund, the National Mobilization Against Sweat Shops, and the Chinese Staff and Workers Association. He also formed the Asian American Mapping Seminar in New York.

Daredevil dancer conquers mountain

Daredevil dancer conquers mountain

Chinese float gives joy at Macy's parade

Chinese float gives joy at Macy's parade

Calm comes to troubled Ferguson

Calm comes to troubled Ferguson

6 things you should know about Black Friday

6 things you should know about Black Friday

Visa change may boost tourism to the US

Visa change may boost tourism to the US

China's celebrity painters

China's celebrity painters

Beauty of Beijing float making debut in Macy's parade

Beauty of Beijing float making debut in Macy's parade

Rescue dogs show skills in NW China

Rescue dogs show skills in NW China

Most Viewed

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|

Today's Top News

China, US fight terror on the Internet

How to give is focus of philanthropy forum

China, US diverge on approaches to nuclear energy

China's local govt debt in spotlight

Macy's looks to appeal to more Chinese customers

Clearer view of Africa called for

Cupertino, California council is majority Asian

BMO Global Asset Management Launches ETFs in Hong Kong

US Weekly

|

|