Going gung ho

Updated: 2011-09-30 09:20

By Liu Xiaozhuo (China Daily)

|

|||||||||

|

|

Former Wall Street consultant puts career on hold to teach future Chinese business leaders

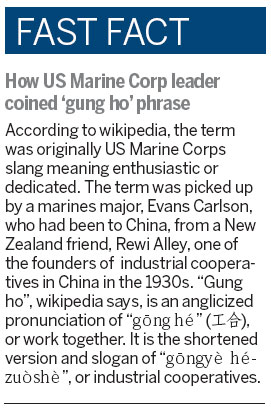

The term gung ho, with its American and Chinese roots, might well have been coined for Alicia Noel. The US-born university teacher has a, go-anywhere, get-stuck-into spirit that these days has her rowing dragon boats in China.

Noel, 40, has been part of the Beijing International Dragon Boat Team for three years, and has traveled to various parts of China to compete with her team. But it is about much more than sport. For her dragon boat racing is a bridge that brings her into contact with people and with places she might otherwise never come across.

"We travel around ... and when you travel as part of a team like that, especially a team that's half Chinese, you learn more than if you just go as a tourist."

She has even competed in the spiritual home of the modern day Dragon Boat Festival, the Miluo River, in the southern province of Hunan, where a government adviser, Qu Yuan, is said to have drowned himself 2,300 years ago in protest at official corruption.

The same teams compete around the country, she says, and the teams and their entourages knock into one another, the same race officials and the same government dignitaries. "We joke that if ... we didn't know one another through dragon racing I couldn't even speak to these people."

In an interview in Noel's Beijing office punctuated by snatches of Chinese and gales of laughter, she tells of her visit to China in 2005. It soon became clear that two days would develop into something far beyond a fleeting sojourn, and she knew that she had business to do with the country.

She arrived here with the dust of several countries on the soles of her feet, having been born in the US, spending part of her childhood in South Africa and later spending about a year in Ecuador.

She studied in New York and later worked in Wall Street as an investor relations consultant, and worked for several years in a government agency as a budget director. She took up a post at the United Nations International Development Organization in Beijing in 2009, and for the past year has taught business at the International College at Beijing, part of China Agricultural University.

With her business and financial credentials, she is keenly attuned to global economics.

"So much business in China [is] done internationally nowadays and more and more Chinese companies are expanding and investing in overseas markets."

But Noel has put her career in the business world on hold to take on the role of a teacher.

She teaches four different classes and two different courses and spends a lot of her time on lesson and assignment planning.

But one of her biggest challenges is getting students to actively participate in the classroom.

She feels this may be because the expectations of Chinese students in what happens in a classroom are a world away from those of their Western counterparts, or for some it may simply be because of shyness.

"Maybe they do not feel comfortable speaking English, so they seldom ask questions."

But Noel has been beavering away at cultivating a classroom atmosphere she thinks will be beneficial to all.

"I make it clear to them that I expect their questions and opinions. If they want to do well and get an A in this class they have to be active," she says.

"As for some of my Chinese students who are naturally shy but are good students and hard workers, I would come closer and speak in a low voice to them That seems to make them feel less awkward (in saying what they think)."

Even though Noel, in a sea of Chinese students, has the perfect opportunity to improve her Mandarin, her mind is firmly closed to that, feeling that it would be improper.

"We do sometimes have brief interactions outside of the classroom in Chinese - I think they appreciate that I am putting in the effort to learn their language, and it helps them relax more around me.

"(But) I think that my Chinese students are supposed to speak English. Their parents send them here to study in English because they are learning international trade and business and they have to be able to speak English."

So at all times she is keen to throw open the opportunities for her students to practice English, she says. And since the subject in hand is business, she will be there to help with that, too.

She tells of a student's father who wanted to export his company's products to Europe.

Early this year the father, unfamiliar with the European market, sought advice from Noel, via his student daughter, on how to make the most of his opportunities.

Noel herself was on unfamiliar ground with their products, but with her broad business experience did some research on the industry in question and passed on the results to the student's father.

"I learned a lot about this industry myself and they got the information they (wanted). It is mutually beneficial."

Many foreigners working in China find that infamously difficult Mandarin, with its four tones, is one of their biggest obstacles, and Noel is no exception. She has been teaching herself and has had help from a private tutor, but because of her job, her opportunities for developing speaking and listening skills are limited.

That is where dragon boat racing can help fill the gap.

Dragon boats are not her only passion. "I love tea," she says, adding that she goes down to the Maliandao tea market in Beijing "more than I should but not as much as I want to".

"I've been able to take not just my waiguoren (foreign) friends but some of my zhongguoren (Chinese) friends ... some of my Beijingren friends there."

As with dragon boat racing, tea and tea culture provide her numerous opportunities for cultural and linguistic bridge building. She recalls that once in Chengdu, one of her favorite Chinese cities, she sat at a table with an elderly man, and the pair proceeded to polish off "a few hours" chatting about tea, even though they barely spoke one another's language.