The lost art of a gallery

Updated: 2013-05-03 09:01

By Sun Yuanqing (China Daily)

|

||||||||

|

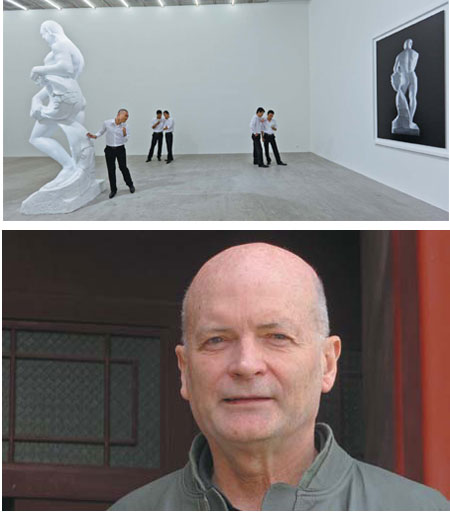

Top: Galerie Urs Meile is a Swiss gallery with a branch in Beijing, exhibiting contemporary arts; Above: Brain Wallace, founder and director of Red Gate Gallery. Sun Yuanqing / China Daily |

Hundreds of Beijing's art galleries look to the local market and artists to see them through troubled times

The winter has passed, but the chill still lingers in Beijing's art districts. With several local and foreign galleries shutting down in the past two years, shadows of doubt are falling on the capital's glittering status as an Asian art center.

In spite of boasting a large community of artists, most of the city's galleries are struggling for attention and support.

Of the 1,560 galleries in China, 742 are in Beijing. Fewer than 7 percent of the national total were able to make ends meet in 2012, says Cheng Xindong, director of the Art Gallery Association and founder of Xin Dong Cheng Gallery.

But like the pictures in their galleries, many are hanging on, hoping to ride out the rough patch and staying loyal and close to their artists.

"The business environment is tough but it's worth it because the artists are here," says Meg Maggio, founder and director of the Pekin Fine Arts gallery. "If anything is driving the bus, it's the artists."

Pace Beijing, the China branch of the New York gallery, says it is still hopeful about Beijing as it tries to fulfill its original intention of "connecting to the local artists".

"They are still the most creative breed in Chinese contemporary art circles. As long as they are here, there will be art," says Li Jia, director of Pace Beijing.

Pifo New Art Gallery, an art space specializing in new and emerging Chinese artists, has a branch in Hong Kong, but says its focus will remain in Beijing.

Threatened by aggressive auction houses and having a loose system of artist representation, Beijing galleries have been battling to survive since they first began to appear on the scene in the early 2000s.

In contrast to the Western art market, where galleries play a dominant role, those in China are reportedly selling less than half as much artwork as the auction houses.

Also, the contracts between artists and the galleries in China are often ineffective.

"The artists in China are very flexible. A long-term, steady relationship and collaboration can be very hard," says Ma Xuedong, executive director of the Art Market Research Center.

While the AGA succeeded last year in getting the authorities to reduce the custom duty on imported art works to 6 percent from 12 percent, value added tax still stands at 17 percent.

A crackdown on tax evasion by art buyers early last year also contributed to the gloom because no clear regulation has been issued yet. This has added to the uncertainty of the market.

"Working in China has become more difficult in recent years due to high import taxes and bureaucracy over the import and export of contemporary art," says Urs Meile, founder and director of Galerie Urs Meile, a Swiss gallery with a branch in Beijing. "If Beijing is to have a chance to play a leading role among the competing art centers in Asia in the future, it is vitally important that those problems are solved and that the structures are improved."

Operating costs in the major art districts in Beijing have also been rising rapidly. Red Gate Gallery, the oldest private contemporary art gallery in China, shut down its branch in the 798 Art Zone in 2008 due to increasing rent. Even in Caochangdi, a newer and smaller art district, Pekin Fine Arts has seen its cost double since it opened in 2005.

However, Guan Yu, director and general manager of Art Market Monitor of Artron in Beijing, believes the core problem facing the city's galleries lies in the absence of criteria in the evaluation of Chinese contemporary art, which can make it risky for collectors in terms of investment. And investment, rather than art itself, is what has been driving the Chinese art market.

"The market is very vulnerable to the changes of the macro economy. People still have money, but because of the slow economy they don't have confidence," says Cheng from AGA.

Last year, the Chinese art market, usually evaluated by auction results, fell 40 percent in annual sales, and was surpassed by the US again. In Sotheby Hong Kong's contemporary Asian art sales last autumn, a benchmark for Asian and Chinese art market, nearly 30 percent of the lots went unsold.

Cheng estimates that average sales for galleries in Beijing in 2012 declined 20 percent from 2011.

Without any substantial support from the government, say in the form of subsidies, the prospects for galleries in Beijing look far from promising, Cheng says.

"If the economy doesn't pick up and the business environment in Beijing doesn't improve, we will see more galleries, both local and foreign ones, pulling out over the next three years," Cheng says.

To survive a time like this, Ma from AMRC believes a gallery has to have either an extensive and established clientele, or strong financial support coupled with grit and determination.

"It is the galleries without long-term plans that are in danger of pulling out," Ma says.

Slashing costs is the obvious response by galleries at present.

The Xin Dong Cheng Gallery is going to do four exhibitions this year, compared with six last year, and will attend three international art fairs, down from seven or eight in the past.

The gallery also plans to work with collectors, corporations and universities to provide professional services in education and consulting to explore new ways of income.

"Galleries need to be more than a trading platform," Cheng says. Developing art-related products is another option.

The Ullens Center of Contemporary Art makes a reported 10 million yuan ($1.61 million; 1.25 million euros) a year from its store sales, which covers about half of its operating costs.

"These products might not be expensive, but they have an extensive base of consumers. And this could be a trend for art galleries in the future," Cheng says.

At the same time, social media-savvy galleries are reaching out to new potential clients via weibo, China's micro-blogging sites.

"Our big strategy since last year is to really develop our social media presence," says Brian Wallace, founder and director of Red Gate Gallery.

While many Chinese galleries don't use social media, those who do usually don't update it for weeks. Red Gate's weibo account had about 54,000 followers as of early April, the most among the galleries in China. It is bringing a new group of clients to the gallery.

"Now we are seeing new people, younger people, mainly Chinese, coming to the gallery," says Wallace. "They are also bringing their friends. There is a whole new generation of people who are young, educated, traveled, interested in art and with money. Some are in their 20s, but also a lot in their 30s and 40s."

Pace Beijing, whose portfolio includes heavyweights such as Zhang Xiaogang and Yue Minjun, traditionally focuses on more established artists, but it is now considering venturing into new territory, taking on Li Zixun, a relatively new Taiwan artist.

"This is our first attempt at diversity, and we will explore it further in the future," says Li Jia.

While the galleries keep their roots in Beijing, they are also seeking new destinations.

Pifo New Art Gallery is targeting the more mature and steady collector base in the West, taking part in major international art fairs this year in the United Kingdom, Germany, Spain and Dubai for the first time.

"The financial crisis might have affected many people, but it is much less felt among high-end art collectors, and they are still buying as long as they find the art to be interesting and affordable," says Wang Xinyou, founder and director of Pifo.

Foreign buyers now account for 30 percent of Pifo's clients, and Wang expects it to rise to 40 percent over the next two years.

With a branch in Hong Kong, Pifo is also considering a new one in neighboring Shenzhen to form a closer relationship with clients in the mainland.

As a tax-free port, Hong Kong has long been Beijing's rival as an Asian art hub. With the opening of M+, a new museum for visual arts, and Art Basel's purchase of the Hong Kong fair Art HK, the competition is becoming even more intense.

While Beijing tops Hong Kong as a source of artists, that advantage is greatly limited by the tax policies and business system operating in the capital.

However, the operating costs in Hong Kong are still much higher than in Beijing.

Pifo's 200-square-meter Hong Kong branch costs HK$300,000 ($38,600; 29,700 euros) a month while the Beijing branch costs 200,000 yuan ($32,300; 24,800 euros) and the space is five times as big.

Maggio from Pekin Fine Arts, who has just opened a gallery in Hong Kong "as a window into Hong Kong's growing art community", says Beijing remains its base.

"Because of the new M+ museum, the art community in Hong Kong is growing very quickly. I don't think it's Beijing or Hong Kong, I think the strategy is Beijing and Hong Kong. The platform in Beijng is not enough for Asia."

sunyuanqing@chinadaily.com.cn

(China Daily 05/03/2013 page12)

Michelle lays roses at site along Berlin Wall

Michelle lays roses at site along Berlin Wall

Historic space lecture in Tiangong-1 commences

Historic space lecture in Tiangong-1 commences

'Sopranos' Star James Gandolfini dead at 51

'Sopranos' Star James Gandolfini dead at 51

UN: Number of refugees hits 18-year high

UN: Number of refugees hits 18-year high

Slide: Jet exercises from aircraft carrier

Slide: Jet exercises from aircraft carrier

Talks establish fishery hotline

Talks establish fishery hotline

Foreign buyers eye Chinese drones

Foreign buyers eye Chinese drones

UN chief hails China's peacekeepers

UN chief hails China's peacekeepers

Most Viewed

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|

Today's Top News

Shenzhou X astronaut gives lecture today

US told to reassess duties on Chinese paper

Chinese seek greater share of satellite market

Russia rejects Obama's nuke cut proposal

US immigration bill sees Senate breakthrough

Brazilian cities revoke fare hikes

Moody's warns on China's local govt debt

Air quality in major cities drops in May

US Weekly

|

|