The West needs to learn, not to teach

Updated: 2013-05-10 07:11

By Giles Chance (China Daily)

|

||||||||

China has made the hard decisions that equip it to dispense economic advice

The head of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, Angel Gurria, visited Beijing in March to attend the annual meeting of the China Development Forum.The OECD wrote a report especially for the forum, titled Stepping Up the Pace of Reform and Fostering Greener and More Inclusive Growth in China. Gurria was joined at the forum by the CEOs and chairmen of 67 large foreign multinationals, other foreign experts such as the Nobel Prize-winning economist Michael Spence from Stanford and the economist Martin Feldstein from Harvard, as well as many senior figures from the Chinese government including. The purpose of the forum was to discuss the options for China's development.

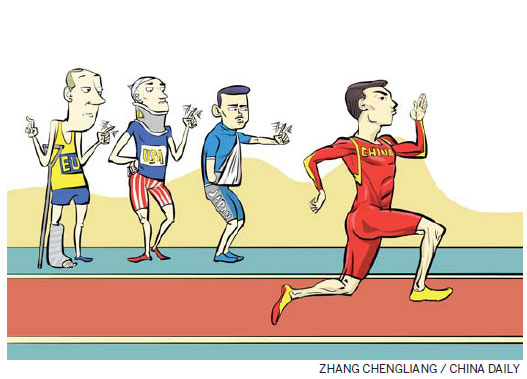

Between 1980 and 2012, China's GDP per person grew 36 fold, and its share of the world economy from 2.2 percent to 15 percent. Over the same period, US GDP per person grew 4.1 times, Japan's 4 times and Germany's 3.9 times, while the combined share of the world economy occupied by these three developed countries nearly halved, from 40 percent to 23 percent. This year China's economy will grow several times faster than its major global peers, and it will be the largest global exporter of capital as well as goods.

So why did businesspeople, government officials and economists travel from around the world to Beijing to advise the Chinese on how to manage the Chinese economy? Should it not be the Chinese who travel to New York, London, Frankfurt and Tokyo to tell the developed countries how to manage their economies?

Almost everywhere you look in the developed world, you can see a failure to deal with serious economic problems. In the US, negotiations between the two main political parties to reduce US government debt have broken down, with no solution in sight.

In Europe, just when everyone was starting to think the euro financial crisis was becoming manageable, a major crisis erupted last month in one of the smallest euro countries, Cyprus. The European authorities, led by the stronger northern euro countries, decided that the rescue depended on a contribution from Cyprus of about one third of the money required to save the two main Cypriot banks, which were insolvent. Cyprus had no option but to take this money from depositors in the two banks. For many Cypriots, suddenly deprived of the economic support they were expecting from the euro political authorities and the European Central Bank in Frankfurt, leaving the euro has become an attractive option.

The solution to the Cyprus crisis proposed by the European authorities was unfair, and undermined the idea of European solidarity that had been slowly and painfully building since the beginning of the crisis in 2010. It showed that the Germans have become tired of financing southern Europe. But it is only a sense of European solidarity that keeps the idea of the euro alive in the face of southern Europe's debt problems.

Many people in other threatened euro countries, such as Spain, Portugal and even Italy, are now thinking that if things get worse in their banks, the euro leadership could do the same to their bank depositors as they did in Cyprus. Keeping savings in a Portuguese, Spanish or Italian bank appears now not to be very smart. If bank deposits start to flee southern Europe for stronger German, Dutch or Swiss banks, the threat to the euro has been put back on the table.

In Japan, following 20 years of economic stagnation, Shinzo Abe, the new prime minister, has come up with a plan to drive deflation out and restore the Japanese desire to invest and spend by printing large amounts of Japanese yen to buy Japanese government debt and other assets. But what Japan needs is fundamental structural change in its economy, including opening up to foreign companies and to modernize its government and corporate structures. If monetary reflation promotes inflation without any real structural change, then the new Japanese recovery strategy may do more harm than good.

Across the developed world, we are faced with the failure of leaders to grasp the underlying and serious reality of the problems facing them, and to find effective solutions. Since the Western financial crash of 2008, central bankers from Ben Bernanke in Washington, to Mario Draghi in Frankfurt and now Haruhiko Kuroda in Tokyo have done everything possible to keep economic growth from collapsing, in order to prepare the ground for a political solution. But it is Western political leaders, not Western bankers, who must grasp their countries' economic problems, and lead their people toward real solutions.

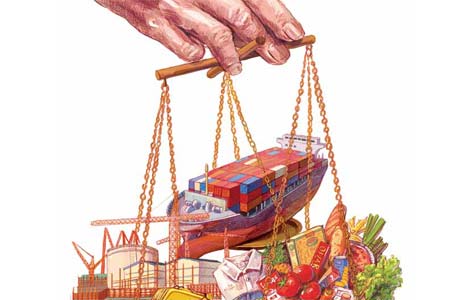

Demand from the emerging countries, particularly from China, has grown fast enough since 2000 to transform the economies of many exporting resource rich countries, such as Australia, Chile and Brazil, and has lifted the economies of capital equipment producers like Germany. But on its own, this emerging country demand is not enough to make the difference to many developed economies. The developed world needs to act urgently to restructure and rebalance, and reduce the dominance of banking and real estate in its economies, so that it can start to grow again.

In Britain, with the backdrop of an economy that today still remains 5 percent below its 2007 output, with debt increasing, and annual price inflation nearing 3 percent, Chancellor George Osborne issued a budget in March that tries to restore consumer demand by rekindling the British love affair with owning private property. But rebalancing the British economy depends in part on a continuing fall in the country's housing prices. Following a British housing boom from 1996 to 2007, British houses remain on average 30 percent too expensive relative to incomes. Osborne's new policy distorts further an already distorted housing market.

Instead, he could have followed China's example of economic stimulus. He could have announced much-needed infrastructure spending that was large enough to persuade investors and British businesspeople that he was really serious about restarting economic growth. As London's main airport at Heathrow becomes ever more overcrowded, a new London airport is obviously needed. A location in the Thames estuary has been suggested, with a development price tag of between 60-80 billion pounds ($91 billion-$122 billion), amounting to about 4 percent of British GDP. Approving and starting this project would have sent a strong signal and employed many thousands of people, while also addressing the worsening airport overcrowding in southern England, a serious problem in a country whose economy depends heavily on international business.

The problems that the developed countries face are serious. But hard times sometimes produce great leaders, who understand the challenges ahead and show their people the way forward. In 1940 Winston Churchill led the British to resist Nazi Germany, while the French people, let down by their weak leaders, were defeated and occupied. And where would China be today without Mao Zedong and Deng Xiaoping?

What the developed world really suffers from today is a lack of courageous and far-sighted leadership. During the good years after the 1980s when globalization was driving an economic boom in the West, politicians in the developed world did not have to worry too much about the economy, because growth was strong, while inflation stayed low. Thinking about their political message and making sure they took the credit for the good times became more important to them than reflecting deeply and dealing with their country's fundamental problems.

Since 1980, China's hard economic circumstances, in particular the size of its population, have forced its leaders to make many difficult decisions. It is the results from those hard decisions that have brought China to its present position of strength. Now there are strong signs that the new government in China is prepared to exercise leadership, and go on making the difficult decisions that will bear more fruit.

Today the leaders of the developed world should be going to Beijing to listen to the Chinese. Not the other way round.

The author is a visiting professor at Guanghua School of Management, Peking University. The views do not necessarily reflect those of China Daily.

(China Daily 05/10/2013 page11)

Michelle lays roses at site along Berlin Wall

Michelle lays roses at site along Berlin Wall

Historic space lecture in Tiangong-1 commences

Historic space lecture in Tiangong-1 commences

'Sopranos' Star James Gandolfini dead at 51

'Sopranos' Star James Gandolfini dead at 51

UN: Number of refugees hits 18-year high

UN: Number of refugees hits 18-year high

Slide: Jet exercises from aircraft carrier

Slide: Jet exercises from aircraft carrier

Talks establish fishery hotline

Talks establish fishery hotline

Foreign buyers eye Chinese drones

Foreign buyers eye Chinese drones

UN chief hails China's peacekeepers

UN chief hails China's peacekeepers

Most Viewed

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|

Today's Top News

Shenzhou X astronaut gives lecture today

US told to reassess duties on Chinese paper

Chinese seek greater share of satellite market

Russia rejects Obama's nuke cut proposal

US immigration bill sees Senate breakthrough

Brazilian cities revoke fare hikes

Moody's warns on China's local govt debt

Air quality in major cities drops in May

US Weekly

|

|