They fought battles on two fronts

Updated: 2015-08-28 05:35

By Chong Hua(China Daily)

|

|||||||||

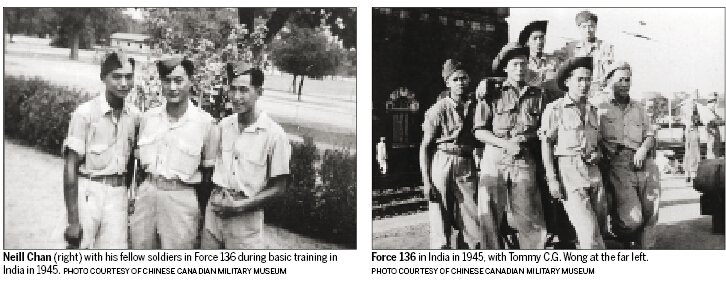

Going overseas

The initial request for Canada to “loan” Chinese soldiers to the SOE in India and Australia referred to the recruits as “wireless operators”. Later requests were for men who could be trained as wireless operators, interpreters, translators, liaisons, propaganda operatives and members of “Jedburgh teams”, who would be parachuted behind enemy lines to perform sabotage and guerilla warfare.

Chan was recruited into Force 136 to interpret military communications for the Indian National Army. In addition to being a native Chinese speaker, he had learned Japanese from friends at Vancouver’s Strathcona Elementary School, even taking jiu-jitsu lessons in Japantown.

Wong was part of another group that trained to become guerillas. Chan later participated in the same training when he discovered there wasn’t a need for more interpreters. There was an exhaustive list they had to learn and pass on to the local resistance.

Besides parachuting, getting in touch with the local Chinese and organizing resistance movements, the recruits “had to learn Morse code, how to blow up bridges and demolitions”, Wong said. “We learned how to telegraph, how to handle explosives, how to use knifes and hand-to-hand combat.

“When they would drop us in, we were [going to be] more or less alone,” he added. “We had to train the local people by ourselves, so we had to know everything.”

The missions would have brought them in direct contact with Chinese Nationalist operatives in parts of Burma occupied by Japan.

“There was a Chinese population in Burma, and at the time the Chinese Nationalists already started organizing some resistance groups, and they sent us in there to train them more in the Western style of war,” Chan said.

In addition to themselves, the Force 136 operatives brought food, weapons and other military equipment for the guerillas and other operatives in the region. They either carried these supplies with them, or the planes would drop the supplies after the operatives were in place.

According to Marjorie Wong, recruits had to volunteer to move to each successive stage of the training and to go on missions. Many did not move onto parachute training. They could still be inserted behind enemy lines by submarine or act as interpreters for the invading British Army.

Of the Chinese-Canadian recruits who trained in India, eight had entered the fi eld by the time of the Japanese surrender in 1945, and two more were dropped in afterward. All the others were in training, and many had formed small teams to prepare for their missions.

“The British knew it was a dangerous mission because they issued us cyanide pills that we were supposed to take with us when they sent us in there, and we were supposed to take [the pills] when we were captured,” Tommy Wong said. “The chances of coming back were not so good.”

What they gained

Wong estimated that he was only about a week away from being called to parachute to Burma when the war ended. He was glad to come home, though he said that the Chinese- Canadian recruits at the time were not fazed by the danger or diffi culties facing them.

“At that time we were there, we made a commitment to go wherever they wanted us,” he said. “When you’re called up and you go active, if you choose to go overseas instead of stay in Canada [for the home defence], then there was no question of not wanting to do something or go somewhere once you’re there.”

Chan said that the recruits in his group were mostly too young to realize what they were doing. Many of the young Chinese Canadians were overseas for the fi rst time and traveling the farthest they ever had in their lives.

“There was just the idea of excitement with your big group,” Chan said. “All I knew was that wherever it is I go, I’ll have some excitement, and that’s that.”

He did admit that almost everyone got malaria at some point, and he suff ered a slew of other diseases, including dysentery and jungle fever.

In between their training, the Chinese group in India got to go sightseeing. “We saw the Taj Mahal, we went to New Delhi and Calcutta,” Chan said. “We learned a lot in India. I saw how the people there lived, did and saw the things Indians did.”

But the most memorable part, Chan added, was when the group was sent into the jungles north of Calcutta between the end of their training and the projected start of their missions.

“We didn’t know what was happening, and they were keeping us there for the time being, so we just learned to live off the jungle,” Chan said. The army supplied only dry rations, so the Chinese group tried hunting for food and took turns cooking.

“Most of the Chinese were good cooks back at home,” he laughed. “We didn’t know anything about hunting, though. I remember some of the boys took their machine guns and shot a wild boar, and when they brought it back to the camp to be cooked … only about a pound of meat was left in the boar. [The rest] was all full of bullets.”

Soon after the Cabinet War Committee reversed its stance on calling up Chinese Canadians for active service, the BC Legislature relented to pressure and granted the provincial franchise to Chinese Canadians serving in the war as well as to Chinese-Canadian veterans of the First World War, though the franchise was not given to the whole ethnic group.

Upon their return to Canada, some veterans of Force 136 actively petitioned the government of Canada to give voting rights to the Chinese community. Contact the writer at chonghua@ chinadailyusa.com

Bolt 'somersaults' after cameraman takes him down

Bolt 'somersaults' after cameraman takes him down

A peek into daily drill of ceremonial artillery unit

A peek into daily drill of ceremonial artillery unit

93-year-old's murals save Taiwan's 'Rainbow Village'

93-year-old's murals save Taiwan's 'Rainbow Village'

Top 8 novel career choices in China

Top 8 novel career choices in China

Hairdos steal the limelight at the Beijing World Championships

Hairdos steal the limelight at the Beijing World Championships

Chorus of the PLA gears up for Sept 3 parade

Chorus of the PLA gears up for Sept 3 parade

Iconic Jewish cafe 'White Horse Coffee' reopens for business

Iconic Jewish cafe 'White Horse Coffee' reopens for business

Beijing int'l book fair opens new page

Beijing int'l book fair opens new page

Most Viewed

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|

Today's Top News

Surviving panda cub at National Zoo is male

China eases rules for foreigners to buy property

Ministry denies troops sent to reinforce DPRK border

Stem cell donor offers ray of hope for US boy with leukemia

All creatures great and small help keep V-Day parade safe

China not the only reason global stock markets are in a tailspin

Market woes expected to delay Fed hike

Gunman had history of workplace issues

US Weekly

|

|