A shot in the arm for vaccination plan

Updated: 2014-05-23 07:45

By Yang Wanli (China Daily)

|

||||||||

|

|

A baby girl receives a routine vaccination jab in Yongnian county, Hebei province. Hu Gaolei / for China Daily |

After adverse publicity resulted in public doubts about the safety of vaccinations, China's health authorities are making moves to boost the inoculation program, as Yang Wanli reports.

At the ripe old age of 40, Wu Jiang has spent the last two weeks attempting to get to grips with WeChat, a popular instant-messaging application in China. As the director of the Immunization Department at the Beijing Center of Disease Control, Wu is keen to learn how his team can use new media to promote awareness of the national immunization program.

In April, the CDC registered a public WeChat account called "Capital Vaccine and Immunization" which sends subscribers regular updates. "Online apps are new to me, so sometimes it's difficult to learn how to use them, but the lack of reliable healthcare information available to the public should be corrected by our efforts. Some people have doubts about the safety of vaccines, so we need to provide them with accurate information. These new messaging tools are all the rage, so why not use them?" Wu said.

Concerns about the safety of domestically produced vaccines have resulted in a decline in the inoculation rate in many provinces. The problem was compounded in December when 17 babies across 10 provinces died after routine inoculations for hepatitis B, a standard procedure for newborns.

The resultant publicity saw the measles vaccination rate in Beijing decline in January by 20 percent, compared with the same month last year, and it's been difficult to regain the trust of the public. "The rate has been climbing since February, but only slowly," Wu said.

More than 90 percent of people with measles will require hospital treatment, and because it's a basic globally used treatment, one that almost every parent will choose for their child, the vaccination rate for measles is often used as an indicator of the overall efficiency of immunization programs.

"After the deaths of the 17 babies, even a few people in the healthcare sector were asking whether vaccination is safe. Misinformation sowed doubts in the minds of the general public. Ironically, the fewer cases of disease we discover after an immunization program, the lower public awareness of vaccination becomes," Wu said.

Free immunization

According to data from the National Health and Family Planning Commission, the national inoculation for hepatitis B decreased by 30 percent in December, compared with the same month the previous year, and the period saw coverage of other vaccinations under the National Immunization Program fall by 15 percent.

Although investigations have ruled out any link between the domestically produced hepatitis B vaccine and the infants' deaths, fewer people are attending free immunization sessions provided by the national program.

In January, the Hainan provincial CDC reported a year-on-year decline of 10 percent in the overall vaccination rate. Meanwhile, in Jiangsu province, CDC officials said the rate fell by 17 percent in the first quarter of this year compared with the same period in 2013.

"Misinformation should be corrected as quickly as possible to reduce the risk of newborn babies getting vaccine-preventable diseases," said Lance Rodewald, a physician with the Expanded Program on Immunization at the China office of the World Health Organization.

Using hepatitis B as an example, Rodewald said the disease is recognized by WHO as a potentially life-threatening condition because it can lead to chronic liver disease and chronic infection. It also increases the risk of death from cirrhosis of the liver and liver cancer. Timely vaccination, starting on the first day of life, is the safest and most effective way to prevent infection.

"If a misunderstanding about safety results in delays to the timely birth dose of the hepatitis B vaccine, there is a risk that many newborns will become infected," Rodewald said, adding that the protocol in the US is to give babies their first dose of hepatitis B vaccine within 24 hours of birth.

In 1992, one in 10 people in China was a hepatitis B surface carrier - people who have contracted the virus but don't display symptoms - and the infection rate was 58 percent, according to statistics provided by the NHFP Commission. Between 1949, when the People's Republic of China was founded, and 1992, 270,000 people died from hepatitis B.

In 1992, the National Immunization Program added the hepatitis B vaccine to the Children's Immunization Program, a move that helped reduce the incidence of the condition to less than 1 percent among children younger than 5 by the end of 2012, a decline of more than 9 percent.

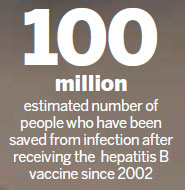

The vaccine has been given free since 2002, resulting in more than 100 million people being saved from infection, according to the NIP.

NYC comptroller honors Chinese businesswoman

NYC comptroller honors Chinese businesswoman

JD records largest IPO of China firms in US

JD records largest IPO of China firms in US

Chinese farmers' art paintings score at UN

Chinese farmers' art paintings score at UN

Star fronts for ancient Chinese city

Star fronts for ancient Chinese city

Former ambassadors ring the closing bell

Former ambassadors ring the closing bell

Silk road shuffle

Silk road shuffle

Largest Chinese group ever is visiting US

Largest Chinese group ever is visiting US

US first lady promotes role of arts in education

US first lady promotes role of arts in education

Most Viewed

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|

Today's Top News

US condemns market attack,experts call for stronger anti-terrorism campaign

Obama puts out 'Tourists Welcomed' sign

Lucy Li, at age 11, makes US golf history

China demands charges be dropped

US should rebalance its 'rebalance' policy

31 dead, 94 injured in Urumqi explosions

China upgrades cyber-security

US must 'get used to China's rise'

US Weekly

|

|