Making inroads to a place where time stands still

Updated: 2012-11-28 10:35

By Hu Yongqi and Li Yingqing (China Daily)

|

||||||||

|

|

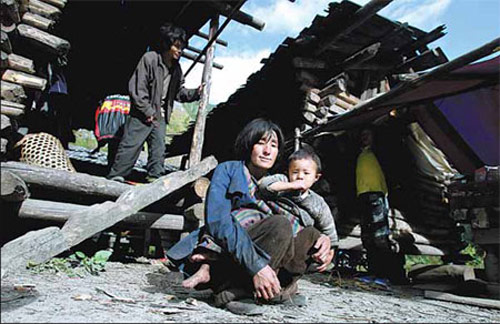

A Derung woman and her child. |

Two decades of change

Traditionally, the Derung did not use money, but believed in absolute equality, even sharing the meat from the pigs that were only slaughtered for New Year celebrations, said Li Heng, a researcher at the Kunming Institute of Botany with the Chinese Academy of Sciences, who conducted an eight-month survey of Dulong River in the 1990s.

During the course of her research, Li discovered that standards of personal hygiene were poor. The locals had no idea how to build toilets and usually "did their business" behind their little wooden houses or just found a private spot. Rainfall provided a natural shower and the locals simply got clean as they walked through the frequent downpours.

The people didn't wash their faces or brush their teeth. Until recently, hot showers were unknown, except for those who were friends with the teacher at the local primary school. In some villages, family members shared one garment and anyone heading into the local township was automatically guaranteed its use, Li said.

In Xiongdang, Kong Zhijue, 22, has made his living by collecting medicinal herbs since he graduated from middle school. The low level of rainfall between June to October provides the best conditions, and Kong can spend as long as five days and nights combing the mountains, carrying only a cooking pot, some rice, a sheet of plastic and spare clothes.

Kong and his fellow collectors tie the bottoms of their trouser legs to prevent irritation from lice and leeches. "The heads of some lice will stay in your flesh after they bite you," said Kong, "Then that part of your body gets inflamed and the bugs have to be cut out of your flesh."

If he gets separated from friends in the thick jungles, he cuts characters into the tree trunks. Anyone coming across the tree responds with a message: "Your friend didn't show up" or "He is back home now".

As most villages gained access to roads, motorcycles became popular. Kong would have to save for more than two years to buy such a luxury, even though the price of the herbs he collects has soared to 500 yuan ($80) per kg, double that of 10 years ago.

Taking care of their 400-sq-m plot of land means that few parents have time to look after their children and so a system has developed whereby an older child from a different family is "borrowed" to act as a babysitter. Even though the local government now allocates 180 kg of rice to each resident annually, the tradition remains.

In contrast with the sobs heard at most funerals, the Derung people laugh instead. They believe that death is natural and therefore there is no point in being sad when it occurs. When one Xiongdang resident died several months ago, his still-clothed body was simply left to decompose close to the banks of the river. No one would tell me his name.

Traditionally, theft is unknown in the area and few mountain residents bother to lock their doors when they leave the house to scout for herb or work in the fields.

Mobile telephony was introduced to the area in 2004. The limited signal capacity means that only 15 people can make calls simultaneously and the service is patchy. Di Yanfang, 19, said she has to walk 4 km from her house in Maku village to find a signal. "Usually I don't use my cellphone too much, but at least it's a sign of progress," she said. The Internet was only connected in September this year.

Hydroelectric generators have provided the region with power since the 1990s, but the supply is unstable and won't sustain television sets. Ma Haoguo, a 51-year-old resident of Qinlandang village, said he hadn't watched TV for 20 years. "How is leader Deng Xiaoping?" he inquired. "Is he in good health?"

When I explained that Deng passed away in 1997, Ma looked surprised.