Book market tries to turn a new page

Updated: 2012-02-17 07:52

By Zhang Yuchen (China Daily)

|

||||||||

|

Visitors take a look around an exhibition of Chinese-language books in London sponsored by China's Hanban before attending the second conference on Confucius institutes in Europe last September. Zeng Yi / Xinhua |

|

A book offering information about China's copyright issues on display at the China hall of the world-famous Frankfurt Book Fair in Germany in 2009. China was guest of honor for the event. Luo Huanhuan / Xinhua |

Publishers branching out but lack of translated works may spoil the plot, Zhang Yuchen in Beijing reports.

Mike Bearden has been burying his nose in books about Chinese culture and history for years. Coming from the United States, he said he was spoiled for choice.

In his native land, shoppers can easily find stores filled with works on China by English-speaking authors. Yet, since moving to Beijing four years ago, he admits he has been disappointed about what is on offer.

"I wanted to learn more about the country through firsthand accounts, and I thought there'd be more translated works of Chinese authors," said the 35-year-old businessman from Seattle. "But there aren't many available."

China's publishing authorities are looking to change that - and fast.

With decision-makers worldwide using cultural exports to boost soft power, China has initiated a "going out" policy that is aimed at taking the country's publishing industry to the next level, at home and abroad.

Along with the Confucius Institute, which is opening schools across the globe, Chinese books are already proving a big draw overseas. China was the guest of honor at the annual Frankfurt Book Fair, the largest of its kind in the world, in 1999, and will have the same honor at the London Book Fair in April.

"Eventually we came to recognize that all cultural productions carry our values," said Chen Yingming, deputy director of international exchange and cooperation at the General Administration of Press and Publication (GAPP). "We definitely prefer to promote works that have our mainstream social values."

He said the government is spending tens of millions of yuan each year to encourage publishing houses - private or State-owned - to broker copyright deals with companies in other countries to boost translation and distribution of Chinese works.

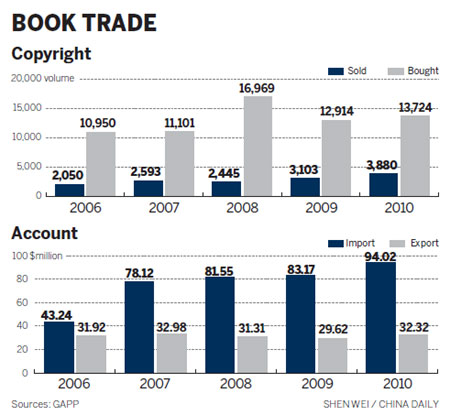

Statistics from the GAPP show that China signed just one copyright export agreement for every 15 imports in 2002. By the end of 2010, however, the ratio was down to 3-to-1.

A major wakeup call came in 2005, when senior officials attending the Beijing International Book Fair said they were shocked to learn that although Germany had sold more than 600 copyright agreements to China the previous year, just one had gone the other way.

"It (the "going out" policy) is not only about promoting the development of China's publishing sector in overseas markets," Chen said. "It's also about improving publishers' creativity in the domestic market."

Broader horizons

Many Chinese publishing houses have already opened branches abroad, with a view to selling more books in mass markets, and are investing more energy into boosting online sales.

"Yet, we have to face the reality that non-English-language books still account for only 2 percent of the total imported by all nations," Juergen Boos, director of Frankfurt Books Fair, told China Daily on Feb 4 during his visit to Beijing.

According to Jo Lusby, managing director of Penguin China, her company publishes five to eight Chinese novels in English-speaking markets every year, while for other languages "it's very little, probably two or three, and they are (mostly) classics".

One major hurdle, added Boos, is the lack of highly trained translators and foreign-language editors in China.

Translators for books about Chinese business, law and literature are usually native speakers with a good background in education and linguistics, such as American sinologist Howald Goldblatt, who worked on best-seller Wolf Totem, and Cambridge professor Julia Lovell.

"There is never a simply literary equivalent in a different language," said Lusby, whose company released Wolf Totem in 2008. She explained that to translate a Chinese book for the English-speaking market takes an "amazing understanding" of both languages and cultures.

The shortage of talent is an issue the GAPP has been trying to address for a while. Since 2008, the authority has been working with Penguin China to run translation-training programs, coaching 20 students each time - half of them Chinese, the other half native English speakers.

However, supply is still far short of demand, not least because the low wages usually offered for translating literature mean many talents shun the work for better paying jobs.

Contemporary works

Joshua Dyer, who studied Mandarin in Taiwan in 2002, has been translating video games and other entertainment products in Beijing for the last three years. He complained that there are not even translated works about popular Chinese culture.

"I want to read a book (in English) that can give me a specific insight, either into the culture or other things. I find I can't read any that offer real firsthand accounts," said the US native, who added that the four or five translated works he had read recently were by English-speaking authors.

Publishers, in an attempt to cater to the overseas market, have released myriad books on culture. However, according to book fair director Boos, literature accounts for just 20 percent of sales on the international market.

"The only modern books I like are autobiographies nowadays," said businessman Mike Bearden. "It's interesting to read about the people who are driving this country."

The desire for alternative works was one of the reasons Li Jingze decided to start Pathlight, a magazine containing contributions from contemporary writers that was launched in December. Foreigner translators translate every word from Chinese to English.

"Although the rest of world gets to peek behind the mystery that is China, people's knowledge about the country still remains the same as it was years ago," he said. "Only three to five Chinese writers today are familiar in the Western literary circles and that's definitely not enough."

Pathlight is owned by Chinese Writers' Publishing Group, which also publishes the 60-year-old People's Literature, and is aimed at those who are hungry to digest China's literature scene, "like a light that shines on a path".

Li, the editor-in-chief, said the magazine will be among the Chinese delegation heading to the forthcoming London Book Fair, where it will promote 18 modern Chinese writers.

Thanks to a healthy number of translators and contributors, Li said he can concentrate on the task of coming up with a different theme for every edition.

Language of the street

Most of the translators at Pathlight are members of Paper Republic, a collection of native English speakers who live in the mainland and are dedicated to bringing more Chinese works to overseas readers.

Working with them "guarantees the quality and makes the work more attuned to our target readership", Li added.

This, says Alice Liu, is no easy task. The executive director of Pathlight, who was born in England, said that to translate literature takes a native English speaker who has learned Chinese by "living on the streets, among the people, puzzling through texts and using them to survive".

The rewards for this labor of love, however, are few. "Usually, we're paid far below what we are worth," Liu said. "That's why good translators always end up doing other things."

For 100 Chinese characters, translators can earn just 30 to 50 yuan ($5 to $8), which means many people can only afford to do it part time. To survive full time, said Liu, translators should earn at least double the usual amount.

Eric Abrahamsen said he believes the answer to the problem lies in "making more people fall in love with China's language and culture".

The co-founder of Paper Republic, who is also an executive editor of Pathlight, said that expanding distribution is crucial, and he welcomed the joint efforts of the government and publishing houses.

The largest exporter of Chinese-language books, with 60 percent of the market, is China International Publishing Group. The company joined forces with online retailer Amazon last year to open China Books, which offers 30,000 titles.

Other companies have also tried to broaden their horizons, including Shanghai Changjiang Publishing Group, which now distributes its products to stores such as Lagardere Groupe and Barnes & Noble, as well as university libraries and museums.

"We play the game the way our counterparts do so we can profit," said Wang Youbu, general manager of Shanghai Press and Publishing Development. "With many people seeking the 'right Chinese book', the foreign-language books in our range offer readers around the globe the chance to understand Chinese culture better."

Beijing bookworm Mike Bearden agreed, and said that the more information that is available, more walls can be broken down.

"The view of China from outside and what China really is are two different things," he added.

Contact the reporter at zhangyuchen@chinadaily.com.cn

(China Daily 02/17/2012 page1)

Relief reaches isolated village

Relief reaches isolated village

Rainfall poses new threats to quake-hit region

Rainfall poses new threats to quake-hit region

Funerals begin for Boston bombing victims

Funerals begin for Boston bombing victims

Quake takeaway from China's Air Force

Quake takeaway from China's Air Force

Obama celebrates young inventors at science fair

Obama celebrates young inventors at science fair

Earth Day marked around the world

Earth Day marked around the world

Volunteer team helping students find sense of normalcy

Volunteer team helping students find sense of normalcy

Ethnic groups quick to join rescue efforts

Ethnic groups quick to join rescue efforts

Most Viewed

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|

Today's Top News

Health new priority for quake zone

Xi meets US top military officer

Japan's boats driven out of Diaoyu

China mulls online shopping legislation

Bird flu death toll rises to 22

Putin appoints new ambassador to China

Japanese ships blocked from Diaoyu Islands

Inspired by Guan, more Chinese pick up golf

US Weekly

|

|