Right to housing: Who can grant it?

Updated: 2012-10-22 07:49

By Fulong Wu (China Daily)

|

||||||||

"Housing for people" is an ancient Chinese utopia. In modern times, this idea has become the "right to housing". However, it does not mean that everyone should become a homeowner. Rather it means granting people access to decent housing as a basic right. During the Industrial Revolution, the working class didn't have the right to housing. The same is true of the poor living in the slums of developing countries.

But who can provide the right to housing? In the post-war era, it was the welfare state. However, despite the large-scale construction of public housing, the mission failed. In many developing countries, incapable governments facilitated the spread of slums, in which self-help and informal housing became the norm rather than the exception. Either too much or too little state intervention can be a problem.

For rapidly urbanizing China, the housing question has become a major challenge. In the past decade, rising housing prices seriously undermined affordability. Moreover, a large number of rural migrants are still drifting outside the housing market.

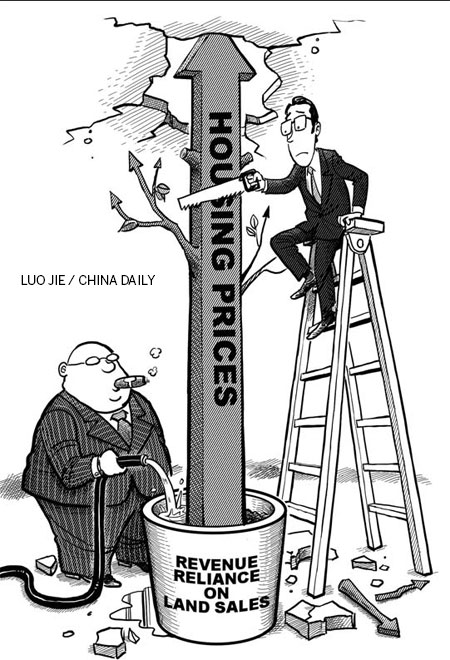

The root of this problem is the "business model" of developing China's economy into a "world factory". Such a business model relies on the entrepreneurial local governments to use cheaper land to attract investment. The arrival of capital led to the influx of migrant laborers into cities, with industrial development stimulating local economies and increasing the demand for real estate. Through compulsory purchase, Chinese cities generate huge revenues from transfer of land-use rights. Hence, cities have become "growth machines", and consequently they are built for capital not for people.

Such state entrepreneurship model has been really effective in capital accumulation. The Chinese economy experienced fast growth in the last decade. Until recently, speculative investment flowed into China on expectations of renminbi appreciation. In addition, the switching of capital from industry to property development by domestic enterprises because of the lucrative return from real estate has further aggravated the frenetic property market.

In this regard, China's property boom shares some similarity with the Japanese bubble in the early 1990s. But the underlying dynamics are more complicated than simple currency appreciation and speculative diversion of investment from the stock market and manufacturing for exports. It is driven by the above mentioned business model and related governance approaches.

Given the potential financial risk and people's growing complaints, the government has taken many measures to restrict housing sale and mortgage lending. Besides, the financial stimulus package designed to cope with the 2008 financial crisis has essentially opened the credit gates and led to inevitable asset inflation and skyrocketing housing prices. With the sluggish economy, the central government requires local governments to build an "indemnificatory housing system", including low-rent housing, affordable housing, price-fixed housing and social rental housing, which is expected to drive economic growth as well as provide for affordable housing.

However, the development of an indemnificatory housing system has not reduced local governments' reliance on the land market. Instead, it has made them draw more resources from the land market for housing projects. Many apartments have been built in inconvenient places that lack basic facilities and are thus lying vacant.

In the process of building these projects, however, low-cost and affordable houses such as those in urban villages are demolished to make way for modern master-planned housing estates. The demolition of old and informal houses has not only driven their occupants to farther off places, but also caused rents to increase. The cost of urban redevelopment is inevitably borne by low-income groups and even the lower-middle class.

In contrast to the common wisdom of low-income housing relying on the State, the informal housing market has proven to be quite versatile and vibrant. Small private builders who leased land from villages and built residential complexes in suburban Beijing can cover the development cost and generate a profit in a couple of years. What hinders the right to housing is the combined force of the land market and the way land is requisitioned, which works for the "growth machine".

To solve the housing problem, China's next leadership should prioritize the right to housing. This does not mean that the government should build more welfare housing - it definitely should not do so by tapping the land market for funds. The State should empower society to help it meet the housing demand. The housing reform should continue and the government should restrain its power in the land market.

There are a couple of ways of doing this. First, property tax should be based on the value of a property. This reduces the incentive of owning luxury properties and will eventually separate housing from economic stimulus measures. As such, housing is first and foremost for residential purposes rather than ownership.

Second, the right to housing should be extended to rural migrants in cities. They should not be forced to try and buy modern high-rise apartments that they cannot afford. Instead of imposing a design standard on their housing, an informal market should be allowed to exist and evolve to suit their needs.

The author is Bartlett professor of planning at the University College London.

Relief reaches isolated village

Relief reaches isolated village

Rainfall poses new threats to quake-hit region

Rainfall poses new threats to quake-hit region

Funerals begin for Boston bombing victims

Funerals begin for Boston bombing victims

Quake takeaway from China's Air Force

Quake takeaway from China's Air Force

Obama celebrates young inventors at science fair

Obama celebrates young inventors at science fair

Earth Day marked around the world

Earth Day marked around the world

Volunteer team helping students find sense of normalcy

Volunteer team helping students find sense of normalcy

Ethnic groups quick to join rescue efforts

Ethnic groups quick to join rescue efforts

Most Viewed

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|

Today's Top News

Health new priority for quake zone

Xi meets US top military officer

Japan's boats driven out of Diaoyu

China mulls online shopping legislation

Bird flu death toll rises to 22

Putin appoints new ambassador to China

Japanese ships blocked from Diaoyu Islands

Inspired by Guan, more Chinese pick up golf

US Weekly

|

|