Hardscrabble life for orphan and 'mom'

Updated: 2012-01-04 08:24

By He Dan and Huang Zhaohua (China Daily)

|

||||||||

Scrap collector didn't register child, causing legal problems

QINZHOU, Guangxi - Wu Tiansheng rushed to pick up an empty soft-drink bottle a passer-by dropped at a busy city square in Qinzhou, South China's Guangxi Zhuang autonomous region, and handed it to his 75-year-old "mother".

|

|

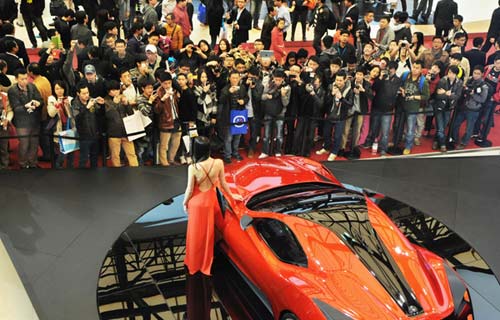

Huang Jinlian, 75, sits with Wu Tiansheng, 7, at her home in Qinzhou, the Guangxi Zhuang autonomous region, in December. Tiansheng was an infant when Huang found him abandoned in a cardboard box, and she took him back home to live with her. Huang Zhaohua / China Daily |

Wu, 7, spends his days helping Huang Jinlian, his "mother", search through trash to collect recyclables.

Huang, a widow, said one summer day in 2005, she and her husband found Wu, an infant with a cleft lip, abandoned in a cardboard box near an alley.

"No one on the street knew the baby or was willing to help, so my husband and I decided to take him home," said Huang, whose claim cannot be independently verified.

Since her husband, her second, passed away last year, Huang has struggled to raise the boy on a monthly income of about 600 yuan ($95) - half of it from a government subsidy, 200 yuan from scrap collecting and 100 yuan from leasing a 20-square-meter apartment her husband left.

Huang and Tiansheng live in a not-so-clean house filled with scraps and furniture recovered from the trash. A rice cooker and a radio are their only electric appliances.

Huang told China Daily she tried to send Wu to a kindergarten, but the boy soon dropped out because his classmates bullied and ridiculed him as the "son" of a scrap collector.

Being the object of mockery, however, is not the boy's only problem.

Worse, yet, is his "gray" identity status.

Because Huang did not report to the police when she adopted the boy and there are no witnesses to prove that the child was abandoned, the local bureau of civil affairs does not recognize the adoption as legal.

Without a formal registration with the civil affairs department, the public security authorities will not issue the child a hukou, a permanent resident's permit.

In consequence, the boy has not been able to attend primary school, and even registering to marry will be a problem for him.

Wu Keming, an official with the bureau, said Huang is unqualified to adopt Wu Tiansheng because she is poor and because she had four children in her first marriage.

"A family that is eligible to apply for adoption would have a stable income. Specifically, its per capita income should be higher than the city average," Wu said.

The official added that nearly 90 percent of adoptions in the city are ineligible and similar to Huang's.

The local civil affairs bureau has suggested Huang send Tiansheng to an orphanage so that he can get a hukou, but Huang won't hear of it.

"I'll raise him until my dying breath," Huang said.

She confessed that part of her motivation is that she wants the child to support her when she is too old to work.

One of Huang's neighbors expressed understanding for Huang's decision.

"The boy is the poor woman's only spiritual support, and it's not an easy thing for anyone to send away a child who you have raised for so many years," said the neighbor, who spoke on condition of anonymity.

Calling Huang's decision "selfish", however, Chen Wei, a lawyer from the Yingke Law Firm in Beijing, said Huang is damaging the boy's rights in the long term.

"Socially, people will sympathize with the old woman, but keeping the boy without informing the police goes against legal procedure and has left the boy with a 'gray' identity status," she said.

Under current law, the government cannot send the child to an orphanage or appeal to a court in such cases, Chen said.

Civil affairs authorities are not authorized to send irregularly adopted children to orphanages, and the law does not punish those who irregularly adopted children, said Ji Gang, director of the domestic adoption department of the China Center for Children's Welfare and Adoption.

China is amending the regulations to empower social workers to conduct an evaluation to determine whether a family is qualified for adoption, Ji said.

"The revised rules will help orphaned children find a adoptive family rather than simply satisfying a family's wish to adopt a child," Ji said.

There may be a solution on the horizon for Tiansheng's identity status: Zhang Daxiao, Huang's oldest son and a 37-year-old bachelor, plans to adopt the boy.

Zhang, a construction worker who earns about 1,000 yuan a month, said he plans to finish the paperwork for adoption and send the child to a primary school next year.

But the boy will continue living with Huang, Zhang said.

Relief reaches isolated village

Relief reaches isolated village

Rainfall poses new threats to quake-hit region

Rainfall poses new threats to quake-hit region

Funerals begin for Boston bombing victims

Funerals begin for Boston bombing victims

Quake takeaway from China's Air Force

Quake takeaway from China's Air Force

Obama celebrates young inventors at science fair

Obama celebrates young inventors at science fair

Earth Day marked around the world

Earth Day marked around the world

Volunteer team helping students find sense of normalcy

Volunteer team helping students find sense of normalcy

Ethnic groups quick to join rescue efforts

Ethnic groups quick to join rescue efforts

Most Viewed

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|

Today's Top News

Health new priority for quake zone

Xi meets US top military officer

Japan's boats driven out of Diaoyu

China mulls online shopping legislation

Bird flu death toll rises to 22

Putin appoints new ambassador to China

Japanese ships blocked from Diaoyu Islands

Inspired by Guan, more Chinese pick up golf

US Weekly

|

|