Parenting by the book

Updated: 2012-06-17 10:43

By Meredith Rodriguez (China Daily)

|

||||||||

Learning how to be a parent led one new mom to the world of translation, and she tells Meredith Rodriguez that she's learning a lot about herself, too.

Many of her old classmates called An Yanling when they saw her name on the cover of a bestseller in China. They had to make sure it was really her listed as the book's translator. English was never her best subject in school.

"I was interested in mathematics as a student," An says. "Translating books was far from my mind. I thought it was for people who major in English."

But while working in an 18-year career as a communications engineer at a multinational company in Beijing, she discovered the parenting book that would lead her to translate and run workshops - what she calls "education for parents".

|

|

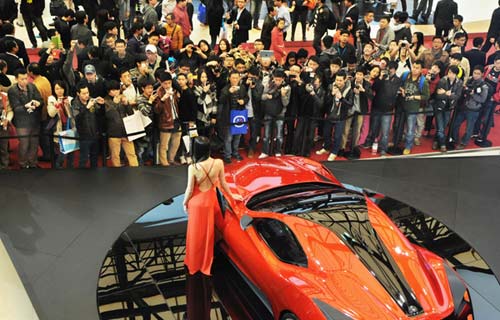

An Yanling says not being an English major has been an asset for her as a translator: She favors small words and short sentences that are easy to understand. [Photo / China Daily] |

Anxiety after the birth of her first and only child in 1997 motivated her.

Like many of her ambitious capital-dwelling peers, An's parents were far away in her hometown in Shanxi province and not around to help two working parents raise their son. Adding pressure was her feeling that she had only one chance to get this parenting thing right, and in a culture much more complicated than the world she grew up in.

An began reading any parenting book she could find, including foreign books. She and five other work colleagues eventually started a parenting club, meeting once a week.

In 2006, a friend brought back from a bookstore in Chicago: How To Talk So Kids Will Listen and Listen So Kids Will Talk. An was struck by its accessibility. She had read many books that emphasized the importance of building a child's self-esteem, she says. "But they didn't tell us how to praise our children, how to respect our children."

This book, written by Elaine Mazlish and Adele Faber, told her what to say, word for word, and often illustrated the instructions with comic-book dialogues. She read it in one night and could not wait to share what she had found the next day.

"I never thought that we could talk to our children like this," An says. "When I read the book first time, I knew it was the manual that I wanted."

The book, originally published in the early 1980s, is still considered the book to read by many US parents, a testament to its timelessness. An's experience is testament to its universality. Parents in her workshops are often surprised that foreign parents have the same problems that they do.

The main premise of the book is that parents should describe rather than judge.

Even praise, if poorly executed, isn't effective in increasing a child's self-esteem. Phrases like "good job" or "you are a good boy" lead children to rely on adult judgment for their self-worth.

The alternative?

Describe what a pleasure it is to walk into a clean room, for example, or point out that the light was still left on, rather than blaming or labeling children when they forget.

Zheng Yi, a parent who co-led the group with An, emphasizes that love is a skill. That was the group's motto.

At first, An quoted the book's cartoon-dialogues directly when facing the situations described in the book. Soon, she understood book's concepts through experience, and the skills became habits.

Her group of about 15 to 20 working parents at Motorola, mostly women, studied the book the way it was intended to be read - together, one chapter per week. Parents returned with questions, doubts about the strategies or cultural adaptations. Some lamented that they do not have school counselors to consult like Western parents or rejected the book's denunciation of punishment as "a little West". Most believed in the strategies but despaired in their lack of self-control to carry them out.

"Even for me, I have practiced for five years, but sometimes I can't control myself," Zheng says about parenting her son, who, she admitted, is "a tester".

"You must encourage yourself," she says, insisting that if you improve a little, your kids will be affected a lot.

An picked key points from each chapter and organized them on a Power Point. One mom posted it on the wall of an online chat room for her child's kindergarten. A publisher found the Power Point on the site, got the rights to the book and figured An was the best person to translate it.

An translated 285 pages in 20 days, she said, 80 percent of which she completed over the weeklong May holiday in 2006. Her son was 7 years old at the time. An did not leave her desk, she recalls. The book was published in 2007 and has been a bestseller in China the last five years. An's updated edition is ready to go to print.

The fact that she wasn't an English major, An believes, was an advantage. She writes simply, using small words, and cuts sentences short, so that the average parent can understand.

Since then, An has translated two other books with the same publisher and recently finished translating, Raise Your Child's Social IQ, a topic that she feels needs emphasis in a nation of only-children. An quit her job last year to pursue coaching and translating full-time. Many of the club's original leaders, like Zheng, have done the same.

An and Zheng believe that ultimately their workshops and translations do not just help people in their roles as parents but improves their communication skills in all areas.

"When I learn how to be a good mom, I know it's a lesson in becoming a good wife, a good daughter, a good employee," An says. "Since my child is my mirror. When I find something wrong with him, usually there is something wrong with me."

Contact the writer at sundayed@chinadaily.com.cn.

Relief reaches isolated village

Relief reaches isolated village

Rainfall poses new threats to quake-hit region

Rainfall poses new threats to quake-hit region

Funerals begin for Boston bombing victims

Funerals begin for Boston bombing victims

Quake takeaway from China's Air Force

Quake takeaway from China's Air Force

Obama celebrates young inventors at science fair

Obama celebrates young inventors at science fair

Earth Day marked around the world

Earth Day marked around the world

Volunteer team helping students find sense of normalcy

Volunteer team helping students find sense of normalcy

Ethnic groups quick to join rescue efforts

Ethnic groups quick to join rescue efforts

Most Viewed

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|

Today's Top News

Health new priority for quake zone

Xi meets US top military officer

Japan's boats driven out of Diaoyu

China mulls online shopping legislation

Bird flu death toll rises to 22

Putin appoints new ambassador to China

Japanese ships blocked from Diaoyu Islands

Inspired by Guan, more Chinese pick up golf

US Weekly

|

|