Cao Kites flying high

Updated: 2012-07-25 07:16

By Liu Xiangrui (China Daily)

|

||||||||

A chance encounter with an unpublished book has turned out to be a life-changing experience for one family. Liu Xiangrui finds out.

Kong Lingmin is better known as "Mr Cao" because of his famous Cao's Kites. When people call him that, he simply smiles and takes the chance to tell them about the long affinity between his family and the old craft.

His father Kong Xiangze, 92, chanced upon an unpublished book by novelist Cao Xueqin - author of the classic A Dream of Red Mansions - in the early 1940s.

|

|

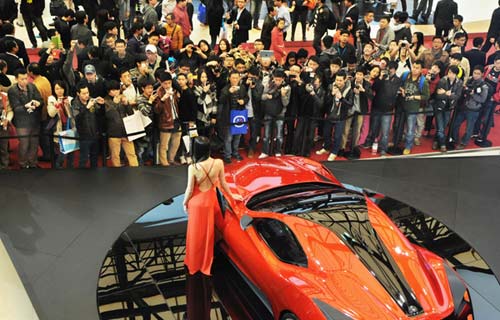

Kong Lingmin, 66, paints a kite at his home, which is filled with kites in every corner. |

In that book are instructions on how to make traditional crafts. Kong's father, then a painting and carving student, learned to make traditional kites by following the instructions in the book. After decades of devotion, he mastered and revived the recorded techniques, and even developed many kites of his own styles.

"My father was very grateful to Cao and insisted he should name the kites as Cao's Kites, instead of Kong's Kites," says Kong, a 66-year-old Beijing native.

Cao's Kites are expensive and considered rare collectors' items rather than playthings.

It probably did not cross the senior Kong's mind that he'd initiated a generations-long commitment in the family when he first came across the book.

In Kong's suburban house, colorful kites of diverse patterns and sizes hang on the walls of their living room.

Scattered on the floors are half-finished kites and bamboo strips. Two big tables in the center of the room are piled full of kite materials and tools - evidence of the family's obsession. Even Kong's wife and son are excellent kite makers. The family always cooperates to complete a kite.

"We make kites in every corner of our home," says Kong's wife Jiao Shufang, 60, who mastered the craft by assisting Kong during the early years.

Kong himself has liked kites since he was a child and learned the art at an early age. He values innovation and believes that traditional crafts should move with the times.

The man likens his work to that of a painter who draws inspiration from nature. He says he spends a lot of time observing his surroundings.

"My head is filled with all kinds of ideas about kites. Everything I see, for example a wine bottle, can become an inspiration and the subject of my designs," Kong says, adding that it's common to spend weeks or even months on just one kite.

The family's affection for kites has deepened with time. They have a collection of their previous works, some dating as far back as decades ago.

"We don't plan to sell them or give them away, no matter how high the offer prices are," Jiao says.

But they had not always worked for passion. Kong and his wife recall the year 1976 when they made kites day and night - for a living.

They had just returned to Beijing from working in the countryside. Having no skills to earn a living, the couple turned to kite making, naturally.

But Kong's father, who had never sold a single kite in his life, forbade them to do so. The senior Kong also reminded the couple of the preface in the book, which stated that the crafts were meant to "help disabled people support themselves with the skills".

"I needed to feed my family. But my father kept Cao's purpose in mind," says Kong.

After pleading and arguing, his father finally relented but made Kong promise to fulfill Cao's ideals.

In the early 1980s, Kong's kites started gaining a reputation. Despite that, Kong, remembering his promise to his father and switched from the profit-making business to become an instructor in Beijing's suburban kite factories.

|

|

Three generations of the Kong family share the same obsession of making kites. |

"I felt more fulfilled with the work. It was good to be able to make a little contribution to society," explains Kong.

In recent years, Kong has set up a kite workshop in his village to impart his skills to the jobless. The workshop, which receives constant orders for its kites, supports one dozen villagers with a monthly pay of 1,100 yuan ($173) each.

"My door is always open to those who are serious about picking up the skills, especially those who are physically disabled," he says.

Due to his declining eyesight, Kong makes only the kite frames most of the time. His wife and son take care of the rest of the work.

But the family has devoted much of their time promoting Cao's Kites' craft and traditional kite culture.

"To many people, flying kites is just a way to pass their time. But there is actually a rich cultural element," says Kong, who is always ready to explain the little details and meanings of each kite.

Kong believes it's equally important to pass on the virtues of cultural heritage. In the case of Cao's Kites, it's about helping needy people, he adds.

To preserve the heritage of Cao's Kites, the family published a book in 2004.

"We want to share this valuable gift from Cao, so that more people will understand his contributions and spirit," explains Jiao.

Kong, who was named as a national inheritor of Cao's Kites in 2006, is strongly against limiting the handing down of craftsmanship only within the family.

"This is not a profit-making tool nor a privately-owned patent," says Kong. "Instead, it's about the responsibility to have more people inherit the heritage so that it will live on and better serve society."

With his wife, Kong often gives classes and lectures on kite craft in schools. He has students all over the country and even overseas.

Kong says he's willing to teach anyone who is sincere about learning the art, instead of those who are simply looking for a money-making craft.

Kong is proud that his 31-year-old son Kong Bingzhang is passionate about carrying on the family tradition.

"I have always loved kites. But it's also my responsibility to promote Cao's Kites," says Kong Bingzhang, who learned kite making when he was a teenager.

An art teacher in a middle school, he has his eyes set on the younger generation. He has opened an optional course on the craft, besides giving lectures and trainings at every chance.

"Many children are not in touch with traditional crafts and cultural heritages," he says. "I aim to sow a seed in their hearts when they are young, so that their love for traditional culture will grow."

Contact the writer at liuxiangrui@chinadaily.com.cn.

Relief reaches isolated village

Relief reaches isolated village

Rainfall poses new threats to quake-hit region

Rainfall poses new threats to quake-hit region

Funerals begin for Boston bombing victims

Funerals begin for Boston bombing victims

Quake takeaway from China's Air Force

Quake takeaway from China's Air Force

Obama celebrates young inventors at science fair

Obama celebrates young inventors at science fair

Earth Day marked around the world

Earth Day marked around the world

Volunteer team helping students find sense of normalcy

Volunteer team helping students find sense of normalcy

Ethnic groups quick to join rescue efforts

Ethnic groups quick to join rescue efforts

Most Viewed

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|

Today's Top News

Health new priority for quake zone

Xi meets US top military officer

Japan's boats driven out of Diaoyu

China mulls online shopping legislation

Bird flu death toll rises to 22

Putin appoints new ambassador to China

Japanese ships blocked from Diaoyu Islands

Inspired by Guan, more Chinese pick up golf

US Weekly

|

|