Last of the reindeer hunters

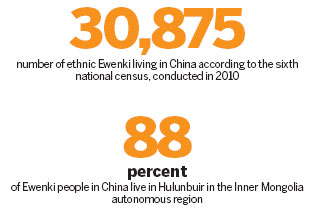

Updated: 2013-10-15 07:35

(China Daily)

|

||||||||

Maintaining traditions

|

|

Ewenki in Aoluguya used to live in tents in the forests, but now most have moved to a new settlement in Genhe city. Photos by Wang Kaihao / China Daily |

The gradual boom in tourism has also provided impetus for a revival of traditional Ewenki culture. Although boats and clothing made from birch bark are hardly practical in the modern word, the method of manufacture has been preserved by the locals. Dekli, who was taught the traditional skills by her mother, sees great potential for the creation of items closer to a modern aesthetic.

Her studio is filled with various types of ornaments and hanging decorations made from reindeer antlers or bones adorned with delicate carvings. Her pieces were once exhibited in Taiwan, earning great praise, but Dekli is seemingly untroubled about the profits she could make if she moved to a big city and opened a store.

"It is only an expression of my emotions," said the 41-year-old, who has also published many works about Ewenki history. "It is the same with my books. I don't want to be famous, I just write whenever deep thoughts occur in my mind."

Aoluguya townships's last shaman died in 1997, but in common with many Ewenki people, Dekli, whose name means "Holy bird on the Shaman's Costume", is still a fervent believer in shamanism, which emphasizes equality and the interaction between humans and nature.

She said that the artisans were recently offered 1 million yuan to make a shaman's costume, but no one took up the offer.

"We are able to make the costumes, but we won't. The priests are wise and sacred. Worship of them will always run in my blood. It would be blasphemous for us to randomly remake their costumes."

|

|

Ewenki in Aoluguya used to live in tents in the forests, but now most have moved to a new settlement in Genhe city. Photos by Wang Kaihao / China Daily |

She was delighted to make a trip to an Ewenki village in Russia recently and was excited to find that she could talk to the locals without any obstacle. Frequent contact with Russian traders over the centuries has resulted in the Ewenki borrowing a large number of Russian words. However, according to Yu, the future of this language, which lacks a written system, is not a cause for optimism.

"Children no longer have the environment to speak Ewenki. Few people under the age of 30 are able to speak it fluently. Protection of the language is more difficult than the survival of ethnic music or arts," Yu said, expressing regret that her half-Ewenki daughter only speaks the language brokenly.

In 2007, when only seven children remained at Aoluguya elementary school it was merged with another school in Genhe. However, all fourth-and fifth-grade students at the new school, no matter which ethnic group they belong to, will study Ewenki in the hope of reviving this endangered language.

"People in Aoluguya older than 60 usually have Ewenki names, while many people in the 30 to 50 age group have chosen Han names," said Yu. "But it's good to see people's awareness of their ethnic identity getting stronger.

"All the parents in Aoluguya are giving their children Ewenki names right now," she smiled. "My daughter is called Alina."

Contact the writer at wangkaihao@chinadaily.com.cn

Storm swamps car insurance firms

Storm swamps car insurance firms

Smartphone firm rockets into the US

Smartphone firm rockets into the US

3 US economists share 2013 Nobel Prize in Economics

3 US economists share 2013 Nobel Prize in Economics

Canton Fair to promote yuan use

Canton Fair to promote yuan use

Vintage cars gather in downtown Beijing

Vintage cars gather in downtown Beijing

Riding the wave of big bargain buy-ups

Riding the wave of big bargain buy-ups

Senate leads hunt for shutdown and debt deal

Senate leads hunt for shutdown and debt deal

Chinese education for Thai students

Chinese education for Thai students

Most Viewed

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|

Today's Top News

All 86 tourists evacuated from Mount Qomolangma

Obama hopeful as meeting nears with lawmakers

Canton Fair to promote yuan use

Over 380 detained in Moscow riot

86 trapped at Mount Qomolangma camp amid snow

Going green can make good money sense

Window cracks for progress in Iran

Senate leader 'confident' fiscal crisis can be averted

US Weekly

|

|