Manchu a window into forgotten past

Updated: 2015-04-03 07:32

By Zhao Xu(China Daily)

|

||||||||

Archaic language is helping historians to solve Qing mysteries, as Zhao Xu reports.

A bereaved emperor who condemned his son to a life of confinement, a bright prince entangled in a deadly political struggle, and a long-gone royal mansion that stood witness to all the love, hate and sadness - Yan Chongnian would have had no chance to uncover this distant past if he did not "hold the key".

"That key was my knowledge of the Manchu language," the historian said, referring to the language used by the rulers of China's last feudal dynasty, the Qing dynasty (1644-1911).

Although viewed by many as the ultimate authority on all issues related to that period, he experienced a moment of uncertainty a few years ago when he was invited to the site of what was once a grand abode for a Manchu wangye, or duke, in a northwestern suburb of Bejing.

"Judging by what remained of the construction - the groundwork and the moat - it was worthy of a wangye," Yan said. "But here lies an apparent contradiction: During the Qing dynasty, wangye lived in the center of the capital, inside what is now modern Beijing's second ring road."

According to Yan, this contradiction had led some researchers to believe the compound, now barely discernible, had belonged to Wu Sangui, a Han general who allied with the Qing at the empire's founding and was made a duke. Yan was unconvinced.

"Not long after that visit, I accepted an invitation to teach at a university in Taiwan," he said. "During that stay in 2008, I spent 10 days searching for information at Taipei's Palace Museum, which is filled with invaluable antiques and documents originally from its counterpart, the Palace Museum in Beijing.

"There, I tripped over a file compiled by the Qing ministry of internal affairs on the completion in 1721 of a royal abode, at the same location as the one I saw in Beijing."

Yan couldn't wait for the end of his semester to fly back to Beijing. "I'd had the story's ending," he said. "What I needed next was the opening."

That was soon found in the countless Qing files kept by the First Historical Archives of China, in Beijing.

"A construction of that scale usually took two to three years to build, so I jumped back to three years before the building's completion and started my search. There, also among the internal ministry's documents, was a file that echoed the one I found in Taipei, not only in content but also the paper and binding. This one was on the commencement of construction, in 1718.

"It was built by Emperor Kangxi (1654-1722), arguably the greatest Qing emperor, for his seventh son, Yinreng. Both files were written in the Manchu language," he said. "I would never have uncovered that history if I hadn't known the archaic language."

Indeed, archaic is the word mostly associated with a language once used by the rulers of the Middle Kingdom, as China was then known.

Courting change

According to Tong Yue, a Qing history expert from Shenyang, in northeastern Liaoning province, where the Manchu originated, the decline of the language started the moment this ethnic people sought to rule over the entire land of China, in the early 17th century.

"The Manchu people, similar to the Mongols 400 years before, came from the northeast to sweep the country by sheer military might, at a time when Han rulers - from the Chinese majority group - had become corrupt and weak," he said. "Dutiful students of history, the Manchu had from the very beginning tried to avoid the fatal mistake committed by the Mongols.

"Instead of imposing on their subjects everything Manchu, the Qing rulers, awed by the much more sophisticated form of civilization they encountered in Central China, borrowed enthusiastically from this newfound cultural wealth, including the language."

Research into Qing government documents gives a clear indicator of how Mandarin had been consistently gaining ground at the court level, Tong said.

"Before Shunzhi, the third Qing emperor, almost all court files were written in Manchu," said Yan Chongnian, the historian. "But things changed markedly under Kangxi, Shunzhi's son, when half of the files were recorded in Mandarin.

"The ratio further increased to seven to three in the following years. And what happened in the larger society echoed this trend."

A love-hate relationship developed between Mandarin and Manchu aristocrats, exemplified by one person - Emperor Qianlong (1711-1799), the dynasty's sixth emperor, who ruled for 60 years.

Alarmed by the waning influence of his native tongue, the emperor issued orders to promote Manchu, including making it compulsory among his children. This did not, however, prevent the literary-minded emperor from penning a reputed 6,000 or more poems, all written in Mandarin in strict accordance to the rhyming and cadence of traditional styles.

Artistic aspiration aside, Tong said the Manchu rulers embraced Mandarin out of the necessity to rule.

"They realized that if they were to stay, they must have meaningful dialogue with the elite class, the literati," he said. "Manchu youths looking for a career at court were required to sit tests and translate writings from Manchu to Mandarin. The emphasis was clearly on Mandarin."

However, it would be unfair to dismiss the role of the Manchu language as merely peripheral, according to Yan.

"You may not believe it, but it was through the language that China's ancient literary and philosophy classics were first introduced to the Western world, in the early 18th century," he said. "The works, mostly on Confucianism and traditional Chinese ethics, were first translated from Mandarin to Manchu by leading Manchu scholars, before they were retranslated from Manchu to English by missionaries in China."

Despite this seemingly tortuous route, Yan said the method best served the purpose.

"It's much easier for foreigners to learn Manchu than Mandarin, as Manchu is alphabet-based," he said. "Moreover, the classics were written in around 500 BC, with its language long becoming obsolete. Without paraphrasing it was virtually impossible for the missionaries to fully understand the allusive, metaphor-infused writing.

"This crucial paraphrasing was done by Manchu scholars trained in China's ancient literary traditions."

Fu Chunbing, an amateur historian in Beijing and a Manchu culture enthusiast, said when two languages meet the infiltration is mutual.

"It's true Mandarin had the upper hand, and gradually nudged the Manchu language into the far corner of people's mind, even by the end of the 19th century," he said. "But by that time, the Manchu language had made numerous tiny inroads into Mandarin, changing it once and for all. This is especially true for the Beijing area, with the largest concentration of Manchu people before the fall of the Qing Dynasty in 1919."

According to Fu, the "old Beijing dialect" - spoken by a dwindling number of elderly indigenous Beijingers - features a large amount of Manchu words.

"It's still unmistakably Mandarin, but many terms would be indecipherable for a modern ear," he said. "People put the stamp of 'old Beijing' on these words, unaware their roots are in the Manchu language."

Spike in interest

Insinuating itself into Mandarin had once ensured the survival of Manchu, at least in parts, yet in an era when a global culture is taking hold at the price of local flavors, its demise seems more or less inevitable, at least to Tong.

"Surveys in the 1950s of people living in a remote Manchu village in northeastern China found most people older than 60 could not only understand but also speak Manchu," he said. "Most people between 60 and 40 could understand but speak very little, while most people between 40 and 20 could only understand the language.

"People in their 20s back then are today in their 80s and 90s. If anything, they offer an apt metaphor for the fate of the language.

"These days," he added, "if you go to one or two very secluded villages in far northeastern China you may still encounter elderly people who speak Manchu, especially when they gossip."

In recent years, television shows dramatizing the court life of Qing emperors and their consorts have sparked an interest among young people in the history and language.

Some have even enrolled in Manchu courses taught by university students majoring in Qing history.

"I've met people who insisted on talking with me in Manchu. Frankly, this is pointless and impractical," Tong said. "During the early reign of the Qing, each year the central government would compile and publish a list of new Manchu words, translated from Mandarin, which was constantly expanding. Not adhering to this list was a crime.

"Today, no such effort toward standardization exists. It effectively means people have to do their own translations when a new word pops up, which happens frequently. The result is conflicted expressions and blocked communication."

Rather than resuscitating the language, Tong said the biggest benefit of studying Manchu is rediscovering lost memories of the past.

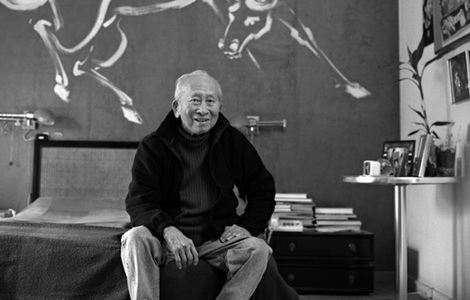

Yan agreed. "Knowing the language has given me a unique, titillating and often tragic peek into history," said the 81-year-old, referring to his findings concerning the history of the royal mansion in suburban Beijing.

Emperor Kangxi ordered its construction for his seventh son, born to his first queen, who died hours after childbirth. Bereaved, the emperor made this son - Yinreng - his legal successor when he was merely 1 year old, only to have him banished when he was 34, reestablished a few years later, and then banished again, sealing his fate one last time.

An intense political struggle is blamed for driving a deadly wedge between a doting father and a son whose early achievement is said to have threatened even his all-powerful father.

Fully aware that Yinreng, like any fallen crown prince, would have to spend the rest of his life in confinement, the emperor built the Beijing compound, which was completed a year before his death at the age of 69.

"Usually, a confined prince would die at the palace," Yan explained. "My guess is the emperor deliberately chose a rather isolated place on the fringe of the capital, to allow his son more comfort and freedom. A heartbroken father and a heartless ruler, Kangxi was both."

Yinreng died three years later in 1725, aged 51, and never lived in the home his father prepared for him, although his son did.

Emperor Qianlong demolished the mansion in about 1740 when he decided it was safer for the descendants of his long-perished uncle to live under his direct watch, near the city center.

"But that's another story," Yan said.

Contact the writer at zhaoxu@chinadaily.com.cn

|

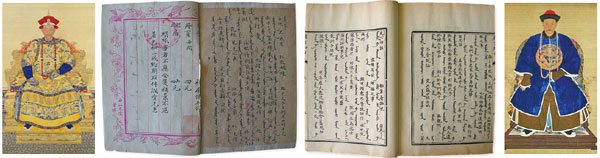

Manuscripts of bilingual books in Manchurian and Mandarin from the Qing dynasty, and portraits of Emperor Kangxi (left) and his son, Yinreng. Provided to China Daily |

|

Classes about the Manchu language and the ethnic group's customs have been given to students at a primary school in the Kuancheng Manchu autonomous county, Hebei province, once a week since December 2013. Of the county's population, 64 percent are Manchu people. Xinhua |

|

A ceremony to worship heaven held by Chinese emperors during the Qing dynasty is reenacted at the Temple of Heaven on Feb 3 last year, attracting about 40,000 visitors. Zhuo Ensen / for China Daily |

(China Daily 04/03/2015 page6)

Top 5 cooperation priorities in the Belt and Road Initiative

Top 5 cooperation priorities in the Belt and Road Initiative

10 destinations for a Qingming outing

10 destinations for a Qingming outing

'Silk Road' captured in planted field

'Silk Road' captured in planted field

Teaching on a rope

Teaching on a rope

Bambi artist, 104, has show in NYC

Bambi artist, 104, has show in NYC

US returns ancient Royal Seal of King Deokjong to S. Korea

US returns ancient Royal Seal of King Deokjong to S. Korea

Snowfall hits China's Urumqi

Snowfall hits China's Urumqi

'Tomb-sweeping services'

'Tomb-sweeping services'

Most Viewed

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|

Today's Top News

Democratic senator pleads not guilty to corruption

China still No 1 for US adoptions

Mainland objects after US fighter jets land in Taiwan

Disgraced former security chief faces raft of charges

Obama: Iran framework could make world safer

China to play bigger intl role: blue book

China remains No 1 for

US adoptions

Death toll rises to 147 in Kenya university attack

US Weekly

|

|