For archaeologist, bones speak

Updated: 2015-09-01 07:45

By Han Junhong in Changchun and Zhou Huiying in Harbin(China Daily)

|

||||||||

Memorial to World War II forced laborers is a 'precious history underground' waiting to be discovered

As the youngest staff member at the Forced Laborers Memorial Hall in Northeast China's Jilin province, Pan Sijie is a keeper of the remains.

Pan, 25, an administrator of cultural relics, unearths the bones of those who died during forced labor for the Japanese during the wartime occupation.

"The precious history underground should be seen and remembered by more people," Pan said.

In April 1937, the Japanese army began building a hydro-electric station on the Songhua River, about 20 kilometers from the center of the city of Jilin.

According to historical records, the army lured at least 110,000 laborers to the project with promises of generous rations and high wages. Once they arrived, they were enslaved, and faced appalling living conditions.

Thousands of laborers died, killed by poor conditions or by soldiers. Their corpses were dumped in a shallow pit 2 km from the dam they were building. In 1963, the memorial hall was built on the site of the mass grave.

"From the remains we unearthed, we can easily find the scars caused by external forces. Some were cut and some had other injuries," Pan said. "They even captured lots of child laborers."

In 2013, after graduating from Jilin University with a degree in archaeology, Pan gave up the chance to become a graduate student to join the memorial staff.

"As an archaeology major, I think it is more important to put the knowledge into practice," she said. "So when I was told that I had passed the memorial's enrollment exam, I decided to choose the job. I hope I can find more evidence of Japan's wartime use of forced laborers through my work."

Japan invaded China in 1937 and ruled parts of the country with brutal force for the next eight years during China's War of Resistance Against Japanese Aggression.

Only one year after Pan started work at the memorial, in August 2014, two more sets of human remains were found. She spent all of her time at the dig, using a small hand shovel and a small brush to uncover them with utmost care.

"The work is really hard. Sometimes I have to crawl in the soil for hours," she said. "But the achievements are worth the hard work."

For Pan, the bones speak.

"It seems that they want to tell us what they suffered at that time," Pan said. "The remains are more like the epitome of the painful history."

Pan sometimes serves as a docent when there are a large number of visitors. Besides explaining how the Japanese army enslaved the forced laborers, she shows the scars on the bones.

"I think the intuitive feeling can shock people directly and make them remember the history," she said.

Two years after joining the staff, Pan wants to put down roots.

"I hope I can unearth more laborers' ossified remains and get more relics about them," Pan said. "In addition, I hope we can develop a mobile phone application that people can use to visit the memorial on the Internet."

She is looking forward to establishing a database of information with the help of Jilin University.

"We don't know how many remain still underground, and I still have much to do and to learn," Pan said.

Contact the writers through zhouhuiying@chinadaily.com.cn

|

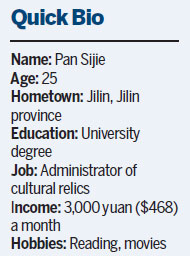

Pan Sijie, a staff member at the Forced Laborers Memorial Hall, carefully removes soil to uncover the remains of Chinese laborers forced to work for the Japanese in World War II. The skeletons were found in Jilin city, Jilin province, a year ago. Provided to China Daily |

(China Daily 09/01/2015 page7)

- Three killed, 8 missing after fishing boat capsizing in S.Korea

- Migration crisis tears at EU's cohesion and tarnishes its image

- Britain signals move towards air strikes in Syria

- Snowden accepts Norwegian prize via video link

- Tokyo ditches Olympic logo amid new plagiarism allegation

- Japan criticized for protest over UN chief's visit to Beijing

50th anniversary of Tibet autonomous region

50th anniversary of Tibet autonomous region

Red carpet looks at the 72nd Venice Film Festival

Red carpet looks at the 72nd Venice Film Festival

China beats Russia in 4 sets at volleyball World Cup

China beats Russia in 4 sets at volleyball World Cup

8th Int'l Military Music Festival 'Spasskaya Tower' begins

8th Int'l Military Music Festival 'Spasskaya Tower' begins

Downpour floods streets in Beijing

Downpour floods streets in Beijing

Veterans attend V-Day anniversary gala show

Veterans attend V-Day anniversary gala show

Military helicopters write number 70 high in the sky

Military helicopters write number 70 high in the sky

Salute to veterans

Salute to veterans

Most Viewed

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|

Today's Top News

Austria, Germany open borders to migrants

Central government steps up economic support for Tibet

China economy enters 'new normal' eyeing 7% growth rate: G20

Troop cuts signal path of peaceful development

Sino-Russian investment fund eyes more deals

Predicting Internet's future without a crystal ball

Silk Road Fund to expand ties with lenders

Intl community echoes Xi's speech at V-Day commemoration

US Weekly

|

|