Removing the deadly legacy of war

Updated: 2015-12-11 07:57

By Xu Wei(China Daily)

|

||||||||

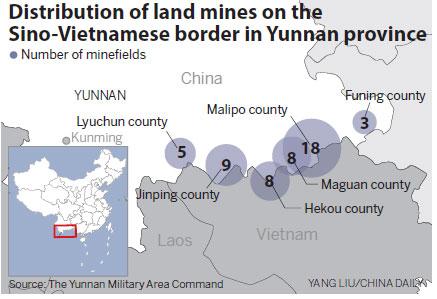

Operations have started to clear thousands of land mines from a section of the Sino-Vietnamese border, with the aim of safeguarding lives, freeing up large amounts of land for local farmers and boosting living standards, as Xu Wei reports from Malipo county, Yunnan province.

Even though a stark sign warning of hidden land mines stands just 30 meters from Wang Qingming's home, the 41-year-old farmer has been injured three times after entering into the danger zone.

Like many residents of Balihe village in the Wenshan Zhuang and Miao autonomous prefecture, Wang has never known a time when land mines didn't pose a threat to life and limb.

The area in the southeast of Yunnan province, close to the Sino-Vietnamese border, was a major battleground during a series of border conflicts between the two countries that flared up sporadically from the late 1970s to 1989.

Tens of thousands of mines were left behind when the fighting finally ended.

The situation may soon change. This week, People's Liberation Army soldiers began demining operations on Dongshan Mountain, the scene of several battles during the border conflicts.

Wang has lost an eye and a leg, and still has more than 80 pieces of shrapnel embedded in his body after accidentally stepping on land mines.

"There were simply too many of them. Maybe I am lucky to have survived in the first place," he said.

Wang is one of 33 Balihe residents to have been injured by land mines. He was first injured in 1986, when he was just 12 years old. "I was bringing the buffalo back from the mountain when a mine exploded. I was too shocked to even feel the pain," he recalled. The accident cost him an eye.

His second injury happened in 1989, also on his own land, and although his life was not threatened, his right leg was so badly damaged it had to be amputated. In 2004, he was injured for a third time as he restored farmland at a former military facility and a mine exploded as he dug into the cement base. His wife left after his third injury, leaving him and their daughter behind.

According to a recent statement from the Yunnan Military Area Command, about 1.3 million land mines and 480,000 pieces of ordnance, such as grenades and artillery shells, were left in the Yunnan section of the border at the end of the conflict.

Since 2000, there have been 81 incidents involving land mines in the prefecture, leaving 12 people dead and 76 maimed, according to the area command. Even after two large-scale clearance operations from 1992 to 1994 and 1997 to 1999, about 470,000 mines and 157,000 ordnance pieces remained.

On Nov 3, the PLA launched a third clearance mission in the prefecture. The operation has given residents fresh hope of a life free from the threat of injury or death. The mission targets 95 minefields in an area of about 52 square kilometers, and aims to clear as many mines as possible, and seal off areas where demining operations are too dangerous or difficult to conduct, before 2017.

"Everybody is hoping that this land will be forever free of mines and terror," said Wang Kaifu, the village head.

"The mountain used to give us everything: firewood, food for our livestock and herbal medicines. We just want it back to how it was before," he said.

Lives on the line

In 1981, Wang Kaifu's father was killed when he stood on a concealed land mine as he patrolled Dongshan Mountain with other members of the local militia. The number of land mine-related injuries and deaths rose steadily in the 1980s, and Wang Kaifu will never forget the smell the mines emitted after they exploded. "It was the smell of TNT mixed with blood. Just a faint whiff could make you nauseous," he said.

As one of the youngest men in the village, Wang Kaifu, 36, has often been tasked with dangerous expeditions, such as entering minefields to carry injured villagers to safety. He said most of the devices near the village are antipersonnel mines, so the force of the blast can rip off a leg or cause blindness, but rarely results in death.

"Even so, that's enough to make your whole life too miserable to endure," he said, adding that several young men in the village took their own lives after being injured by land mines.

During the clearance miss-ions in the 1990s, the provincial government erected signs to alert villagers to the hidden danger, but Wang Qingming said it's impossible for the locals to avoid the minefields completely.

"We have no alternative. We need to go to the mountain for firewood and food for our livestock," he said. "For us, the supply of natural gas or liquefied natural gas only exists in our dreams."

Wang Kaifu said most of the injuries occur when villagers are fetching fodder for their pigs. "There is no other source of income, so we have to risk it," he said.

In the danger zone

The mountainous terrain and dense forest cover present harsh challenges to the members of the PLA demining teams, according to the officers.

"Nobody knows for certain where each mine was laid, or where they are right now," said Cheng Dengquan, a lieutenant colonel who commands a minesweeping unit on Laoshan Mountain, the scene of intense fighting during the border conflicts. "We can sense the eagerness of the villagers because they sent welcome messages the minute we arrived," he said.

The mines were laid by several different PLA units over a number of years, according to Cheng: "That's why the mines along the border were distributed in a very chaotic manner."

Wang Kaifu said the villagers are grateful to the soldiers, and will use their local knowledge to help them unearth the devices with as little risk as possible. "For them to conduct a mission in an area with which they are totally unfamiliar is a massive challenge in itself," he said.

The third mission is necessary because the two previous operations were unable to clear all the mines scattered across the area. When the previous missions were undertaken, the line of the border was the subject of high-level negotiations that lasted until 2009, when the issue was finally resolved.

However, many of the soldiers involved in the latest mission have accrued a huge amount of experience, either through previous operations in the area, or through miss-ions undertaken as members of UN peacekeeping forces.

Zhang Zhongjun, a sergeant commanding a mine-detection squad near Laoshan Mountain, said the mission will be more difficult this time around because the troops will have to climb the steep mountain slopes wearing protective gear that makes it difficult to move freely.

"But we are much safer when we wear the gear. Even if a mine does explode, it will probably only cause a relatively minor injury, such as a fracture," the 22-year-old said, adding that the team faces far more pressing challenges. "Sadly, our demining robots and other high-tech equipment are virtually useless here because of all the steep slopes and dense jungle," he said.

Cheng, the lieutenant colonel, said most of the minefields in the area are inaccessible by vehicle, and after lying concealed for so long, the mines may have degraded over the years, making them doubly dangerous. They will almost certainly have shifted position too, disturbed by the heavy rains and flooding to which the area is prone.

Looking forward

The widespread distribution of land mines has been a contributory factor to the grinding poverty that afflicts many villages along the Yunnan stretch of the border, according to Hou Renxu, Party chief of Jinchang township in Maguan, a county close to Malipo.

More than 5 sq km of the land in and around Jinchang is still littered with mines, and Hou said many residents have been injured as they tried to lead their livestock out of minefields, although last year, only one resident was injured.

"Every time a villager is injured, a sense of anxiety spreads among the people. Even if we manage to clear all the mines, the trauma will live long in their lives," he said.

Wang Kaifu is mulling building a museum of mines and explosives near the Balihe village so future generations will understand the pain the older residents endured. He plans to collect mine cases, grenades and artillery shells, then repaint and exhibit them to explain how they function and how to deactivate them.

"We need to explain to future generations that the mines were everywhere here, and that they are part of the painful history of our village," he said.

Contact the writer at xuwei@chinadaily.com.cn

|

Soldiers use Chinese-made mine-clearing equipment in Yunnan province in November. About 470,000 land mines are thought to be buried in areas along the Sino-Vietnamese border in the southwestern province. Photos by An Yuan / China News Service |

|

Soldiers employ flamethrowers at the edge of a minefield to clear paths for demining operations. |

(China Daily 12/11/2015 page6)

- People exit rebel-held area in Syrian peace deal

- Two DPRK music groups to perform in China

- False bomb alert prompts security measures at Mexico City airport

- Russia fires missiles at IS positions

- US House passes bill to tighten visa waiver program

- Obama, Modi vow to secure 'strong' climate change agreement

US returns 22 recovered Chinese artifacts

US returns 22 recovered Chinese artifacts

AP photos of the year 2015

AP photos of the year 2015

Miss World contestants visit welfare center in Hainan

Miss World contestants visit welfare center in Hainan

Giant pandas brave the cold by settling in freezing north

Giant pandas brave the cold by settling in freezing north

World Internet Conference host Wuzhen: Charming water town

World Internet Conference host Wuzhen: Charming water town

7 half-pound mutts become first test-tube puppies in world

7 half-pound mutts become first test-tube puppies in world

Panchen Lama enthronement 20th anniversary celebrated

Panchen Lama enthronement 20th anniversary celebrated

Printer changes the chocolates into the 3rd dimension

Printer changes the chocolates into the 3rd dimension

Most Viewed

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|

Today's Top News

Shooting rampage at US social services agency leaves 14 dead

Chinese bargain hunters are changing the retail game

Chinese president arrives in Turkey for G20 summit

Islamic State claims responsibility for Paris attacks

Obama, Netanyahu at White House seek to mend US-Israel ties

China, not Canada, is top US trade partner

Tu first Chinese to win Nobel Prize in Medicine

Huntsman says Sino-US relationship needs common goals

US Weekly

|

|