How much tax to levy? There are no easy answers

Updated: 2016-02-22 08:09

By Zheng Yangpeng(China Daily)

|

||||||||

As China prepares a fresh round of tax cuts, economists are airing different views on how much the society is, or should be, paying to the government.

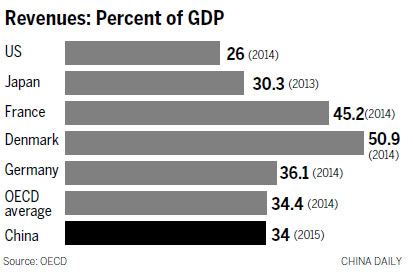

Economists call a country's total revenues from all sources its macro tax burden, measured as a proportion of GDP.

In China, however, "government revenue" is a tricky concept, given the complexity of the revenue stream.

China's fiscal budget consists of four separate accounts: general fiscal revenue (including taxes and fines), special-purpose governmental funds (including revenues from land sales), social security funds and returns from State-owned assets.

Measured by the narrowest definition - the revenue-to-GDP ratio - China's official tax burden is modest. In 2015 revenues totaled 15.22 trillion yuan ($2.4 trillion), or 22.5 percent of China's GDP, which is in line with the World Bank's 22 percent optimal ratio for upper-and middle-income countries.

However, most economists agree that at least part of the special-purpose governmental funds, as well as social security payments, should be included as "revenue", because they are also levies on enterprises and households. The 34-nation Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development includes them when comparing the macro tax burdens of its members.

If land sales revenues are subtracted (economists dispute whether to include it), government revenue in China would be 29.1 percent of GDP. The Finance Ministry has adopted that interpretation, saying the International Monetary Fund doesn't count land sales as government revenue.

If all four accounts are combined, China's total government revenue in 2015 may have hit 23 trillion yuan, or 34 percent of GDP. It was down 1.7 percentage points from 2014, the first time in years the ratio has subsided.

"The weakness in the overall economy weighed on revenue growth, which for the first time in years underperformed GDP growth and caused the tax burden ratio to decline," said Hu Yijian, a tax professor at Shanghai University of Finance and Economics.

China's fiscal revenue growth in 2015 slowed to 5.8 percent, its slowest pace since 1987, when GDP grew 6.9 percent. Land sales tumbled 21.4 percent from a year earlier because of a downturn in the property market.

But 2015 was a departure from the past decade, during which fiscal revenues expanded much faster than the overall economy.

Although China cut taxes in 2015, contributing to a lower revenue-to-GDP ratio, the country's tax burden last year, measured in the broadest terms, was still higher than many others, even some developed countries. Members of the OECD had an average ratio of 34.4 percent.

"China's government is large and should not increase," said Lin Shuanglin, director of the China Center for Public Finance at Peking University. He said the ratio might have reached its peak.

However, "it is not a matter of the lower the ratio, the better", he said. "Many countries, such as Indonesia and Thailand, have very small governments and macro tax burdens around 20 percent, and are struggling for needed public infrastructure.

"What they need is to raise their tax revenues," he said.

- Green cards decision to bear fruit for foreigners

- Beijing to raise level for air pollution 'red alerts'

- Fake story sparks cyberspace reliability fears

- Missing children found safe in nearby village

- Rich Chinese splurge on sportswear as luxury's lustre dims

- Urgent remedy sought for pediatrician shortage

The world in photos: Feb 15 - 21

The world in photos: Feb 15 - 21

China Daily weekly pictures: Feb 13-19

China Daily weekly pictures: Feb 13-19

Lantern Festival in the Chinese paintings

Lantern Festival in the Chinese paintings

Meet Melanie, the real-life mermaid

Meet Melanie, the real-life mermaid

Samsung unveils new products at mobile conference in Spain

Samsung unveils new products at mobile conference in Spain

88th Academy Awards Governors Ball Press Preview

88th Academy Awards Governors Ball Press Preview

Chinese photographers' work shines in major photo contest

Chinese photographers' work shines in major photo contest

Egg carving master challenges Guinness World Record

Egg carving master challenges Guinness World Record

Most Viewed

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|

Today's Top News

What ends Jeb Bush's White House hopes

Investigation for Nicolas's campaign

Will US-ASEAN meeting be good for region?

Accentuate the positive in Sino-US relations

Dangerous games on peninsula will have no winner

National Art Museum showing 400 puppets in new exhibition

Finest Chinese porcelains expected to fetch over $28 million

Monkey portraits by Chinese ink painting masters

US Weekly

|

|