Mandarin Rising

Updated: 2016-11-11 12:34

By Anthony Warren(China Daily USA)

|

|||||||||

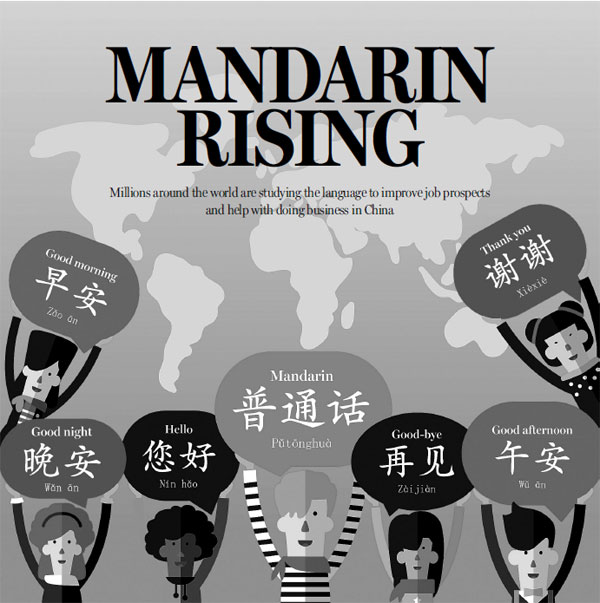

Millions around the world are studying the language to improve job prospects and help with doing business in China

If there was ever a time when learning Mandarin Chinese was just for fun, it is long gone. As Hong Kong-based teacher Molly Huang noted, students today want to know the language primarily for one reason - job prospects.

Huang has seen firsthand the surging interest in Mandarin. She moved to Hong Kong from South China's Guangdong province to teach the language and has had a wide variety of students.

With the growing foreign presence in South China's financial and commercial hubs, a lot of businesspeople are now learning, she said.

Other eager pupils include ethnic Chinese from overseas who aim to reconnect with their roots, and Hong Kong people for whom Cantonese is the mother tongue.

With so many taking up Chinese for business, what about the ones learning for leisure, for fun?

"I don't think there are many of those," Huang said with a laugh.

For more than a century, English has been the world's lingua franca. From commerce, to travel, science and the internet, its stranglehold has been nearly absolute.

Many experts now believe that English will face stiff competition in the coming years. As China helps drive the global economy, a Chinese language craze is sweeping the world. Millions are now studying Mandarin, the official language of China and much of the diaspora.

While more private sector businesspeople aim to talk the talk and build guanxi (relationships), governments too are hoping to broaden their citizens' job prospects. Teaching the language to young students has become a priority for many countries.

"The number of foreign students who are learning to speak, read and write Chinese is greater now than ever before," said Robert Bauer, an honorary professor of linguistics at the University of Hong Kong.

The Cantonese language expert has a background in teaching and studying minority languages within Sino-Tibetan linguistics.

"Education systems have been introducing Chinese language programs into elementary schools because educators know that young students absorb foreign languages like a dry sponge soaks up water," Bauer said.

In the United States, more than 200 schools now teach Mandarin to elementary school students, a tenfold increase in a decade.

In September, Vietnam reported that it would soon introduce Chinese as a compulsory language in its schools.

Meanwhile, across South Africa, 44 schools introduced Mandarin this year as part of a continuing rollout.

According to Hanban, the government department that manages official overseas Chinese education, 100 million people took to studying the Chinese language last year, up from fewer than 30 million in 2006. And many of these learners appear to be in the Asia-Pacific region.

"I am inclined to think that Chinese will eventually become a second language in many parts of the world," said Chu Hung-lam, a professor and director of the Confucius Institute of Hong Kong.

"The language itself is a factor; it is beautiful and rich and is not difficult to master.

"But it will take at least half a century or so to reach the stage of being spoken and written by most of the high school and college students in the world."

This is all part of a slow decline in English as a native language. In the mid-20th century, almost 10 percent of the world spoke English as their first language due to the legacy of British colonialism and American consumerism, according to English linguist David Graddol in his 2000 paper, The Decline of the Native Speaker.

By 2050, however, the number of native English speakers is likely to drop to less than 5 percent, while non-native English speakers would make up half of the world's population, according to Graddol.

Some linguists see two possible futures for Mandarin. One is that Chinese will become the common language of Asia in the 21st century, as business and communication grow.

Another possibility, according to linguists like Andy Kirkpatrick, a professor at Griffith University in Australia, is that with English already the working language of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations, non-native forms will evolve. Though these new versions of English might borrow Chinese words for convenience, as seen in Singapore and Malaysia, it would be an amalgam, not a true Mandarin lingua franca.

But if Mandarin is to stake that claim, it has its work cut out. With four tones or pitches, each of which must be perfected to convey a spoken syllable's meaning, and a written system that relies on thousands of characters (hanzi), it is often regarded as one of the most difficult languages to learn.

Chu disagreed. "The Chinese language is not difficult to learn or master, no more difficult than English," he said. "But, the Chinese characters are a real challenge to the learner, (whether he or she is) Chinese or not."

Still, the pitfalls are not lost on the Chinese government. For decades it has been promoting Mandarin in a nation with thousands of dialects and numerous minority languages.

In 2014, the Ministry of Education reported that about 30 percent of China's 1.3 billion population could not speak Mandarin. Of the other 70 percent, it said only 10 percent could communicate in the language articulately.

If one country has recognized the need to turn to Asia's most widespread language, it is Australia.

Since 2012, Australia's education system has been pushing for what it calls the Asian Century. According to the government report that launched the project, only 130 Australians with a non-Chinese background have Mandarin proficiency, and half of those are aged 55 and above.

Although there are no global figures, anecdotal and local evidence implies that a majority of Chinese second-language learners are ethnically Chinese.

According to Chinese Language Competency in Australia, a report released last year by the Australia-China Relations Institute of the University of Technology Sydney, fewer than 400 of the 4,149 students in Australia who studied Chinese in their final school exams were of non-Chinese ethnicity.

A major cause of this was believed to be the Chinese writing system. When Australians leave school, having learned 500 Chinese characters, for example, it is only the equivalent of a grade-school education in China. Students in China learn up to 6,000 characters by the time they graduate.

Ironically, learners of the language in China and abroad rarely start learning characters from the traditional books of teaching. New students instead start by using the Latin alphabet to write Chinese.

This system, called pinyin, is understood by the majority of Chinese and it is not uncommon to find it used in casual written communication. But it is rarely, if ever, used in formal writing.

anthony@chinadailyapac.com

- Online shopping frenzy sparks trash concern

- Is it a thing? 10 odd jobs where you can make good money

- Message on a bottle: Mineral water company launches drive to find missing children

- Snow leopards caught on camera

- A foreigner's guide to Singles Day shopping spree

- China jails 49 for catastrophic Tianjin warehouse blasts

- Americans want to change presidential election system

- UK business calls for exclusive visa system for post-Brexit London

- Australia poised to sign refugee deal with United States: media

- Philippines' Duterte says he is against 2014 defense pact with US

- S.Africa wants to work with US in promoting peace: Zuma

- Trump's victory on global pages

Alibaba breaks sales record on Singles Day

Alibaba breaks sales record on Singles Day

Ten photos from around China: Nov 4-10

Ten photos from around China: Nov 4-10

Snow storm hits Xinjiang

Snow storm hits Xinjiang

Clinton concedes election, urges open mind on Trump

Clinton concedes election, urges open mind on Trump

Places to enjoy golden gingko tree leaves

Places to enjoy golden gingko tree leaves

Taobao village gets ready for shopping spree on 11/11

Taobao village gets ready for shopping spree on 11/11

Overhead bridge rotated in East China's Shandong

Overhead bridge rotated in East China's Shandong

The 75th anniversary of Red Square parade celebrated

The 75th anniversary of Red Square parade celebrated

Most Viewed

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|

Today's Top News

No environmental shortcuts

US election rhetoric unlikely to foreshadow future US-China relations

'Zero Hunger Run' held in Rome

Trump outlines anti-terror plan, proposing extreme vetting for immigrants

Phelps puts spotlight on cupping

US launches airstrikes against IS targets in Libya's Sirte

Ministry slams US-Korean THAAD deployment

Two police officers shot at protest in Dallas

US Weekly

|

|