A visionary ahead of his time

Updated: 2016-11-11 12:34

By Zhang Kun in Shanghai(China Daily USA)

|

|||||||||

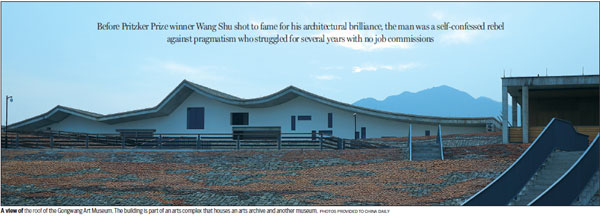

Before Pritzker Prize winner Wang Shu shot to fame for his architectural brilliance, the man was a self-confessed rebel against pragmatism who struggled for several years with no job commissions

When officials of Fuyang approached Wang Shu in 2012 with an offer to have him design an arts center, the Pritzker Prize-winning architect had a rather unusual condition.

He wanted to have a hand in designing homes for the local villages as well.

Fuyang is located about an hour's drive from Hangzhou, Zhejiang province and it sits on the north bank of the Fuchun River, a place renowned for its natural beauty. Earlier this year, it became a district under the city of Hangzhou.

The local administration promptly acceded to Wang's request. The prospect of securing the services of this famous figure in the architecture world was reason enough to do so. In a display of just how much they revered Wang, the local authorities dedicated a prime piece of land near a mountain and by a river to the arts center.

Should that piece of land in this location be used for real estate development today, it would be valued at a staggering 1 billion yuan ($150 million). Such was Wang's influence.

The arts center will comprise three buildings, Gongwang Art Museum, Fuyang Archives and Fuyang Museum, all of which will be designed by Wang. The Gongwang Art Museum is already open to public while the other two segments are still undergoing construction.

Wang, 53, is the first Chinese to win the world's top prize in architecture. Based in Hangzhou, Zhejiang province, he is currently the dean of the School of Architecture at the China Academy of Art.

Wang grew up in Xinjiang Uyghur autonomous region, where his mother worked as a school teacher. During the "cultural revolution" (1966-76) when schools across the country shuttered, teachers and many others were forced to become farmers. As a young boy, Wang enjoyed working in the fields as it enabled him to feel a connection with the earth. He said that he also found fulfillment in physical labor.

Wang loved reading and had fortuitous access to a range of books censored by the government when his mother was transferred from the fields to become a librarian.

When he was 10, Wang moved to Xi'an of Shaanxi province where he attended lessons in tents instead of classrooms. He later came to witness how the locals would build new classrooms and was fascinated with the bamboo frameworks used in the construction process.

As Wang was passionate about art and engineering, he decided to study architecture in Southeast University because he thought the discipline was a perfect blend of the two. He described himself as a rebellious undergrad who was always ready to challenge professors. Wang even wrote a thesis criticizing modern Chinese architecture.

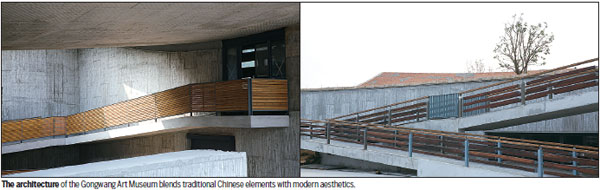

A keen lover of traditional Chinese art, with a particular interest in ancient gardens and landscape paintings, Wang was eager to incorporate the aesthetics and building techniques of such places in his own creations.

But he was perhaps too ahead of his time, because no one in China's architecture scene acknowledged or understood his ideas. For several years following his graduation, Wang had no commissions to work on.

Wang said that it was his wife Lu Wenyu who filed the rough edges off his personality. In 1997, the two of them founded the Amateur Architecture Studio. In his new book To Build House, Wang paid tribute to his wife, conceding that "for the first seven years of our married life, it was her who supported me".

The couple lived an idyllic life in Hangzhou where they would often stroll along the West Lake and had plenty of time to spend sipping tea with friends. Wang said that this calming experience nurtured his heart and in turn evoked a change in his perspective to life.

"You could spend a long time watching the rain, how it falls along the ridges of a building, how the streams flow and where the water drops. All this interests you. You would be thinking if it is possible to design architecture and show clearly where the rain comes from, where it flows, where it goeseach turning and change in movement touches one's heart," he said.

Wang's unique style was eventually recognized and he was presented with the opportunity to design the Ningbo Museum in Zhejiang province. Construction of the museum, which featured the use of bricks salvaged from old buildings that were demolished to make way for modern developments, took place from 2004 to 2008.

Wang said that he had built the structure as if creating a landscape painting.

"Looking at the museum from afar, you see the building as a painting of a mountain that is spreading out right in front of your eyes. When entering the structure, you'll find different landscapes at different positions, offering different perspectives. This is how traditional Chinese landscape paintings should be experienced, through free shifts of perspectives and angles," said Wang.

Following this project, Wang was a part of the World Expo 2010 in Shanghai where he designed the Tengtou village pavilion, which was inspired by a painting of a mountain dwelling by Chen Hongshou (1599-1652). He said that stepping into the doorway of the pavilion is akin to entering a cave where different landscapes unfold at every turn of the step, like "a page in an ancient leaflet of small paintings".

Wang also gained international recognition for designing a building in Xiangshan Campus at the China Art Academy in suburban Hangzhou district.

In 2012, Wang received the biggest accolade that most people in his profession could only dream of getting when he won the Pritzker Architecture Prize. The Pritzker jury had also praised Wang's "unique ability to evoke the past, without making direct references to history", while calling his work "timeless, deeply rooted in its context and yet universal".

Wang described his approach as a combination of ancient aesthetics with modern utility. As an architect working in contemporary China, he believes "one has the opportunity to create something great, something lasting longer than his own life span."

For the Fuyang project, Wang was determined to re-ignite the ancient Chinese admiration for mountains and rivers which embody a unique Chinese philosophy about seeking a life that is in harmony with nature. This was why he had laid out his unusual condition about designing homes for local villagers.

Together with his employees from Amateur Architecture Studio and students from the China Art Academy, Wang visited 290 villages in the area to inspect old houses and be immersed in the traditional way of life. He said that nature plays an integral role in the rudimentary yet charming way of life in such areas which is today on the verge of extinction. He lamented how many of the homes being built in the country today are soulless "American-style big villas" or "fake antiques" with white walls and grey tiles.

Wang used the smaller residential structures in the village as a canvas for the experimentation of his ideas. He used stones, old tiles and materials that are usually considered worthless to construct new village homes and this process helped him determine what he would do for the design of the Gongwang Art Museum.

While the Gongwang Art Museum might be a large compound, its imposing size is tempered by the roof's long and soft curves which are reminiscent of the mountain ridges in the distance.

But not everyone was in awe of Wang's creations. Some have raised their concerns with leakage issues, high maintenance and how his buildings are too distinctive in style, which in turn steal attention from the exhibits on display.

However, Li Lei, director of China Art Museum Shanghai, begged to differ, saying that a fine piece of architecture like what Wang has created is "a bold challenge to pragmatism".

"The building itself is a piece of artApart from the skyscrapers that are mushrooming all over China, the country needs architecture for aesthetic appreciation and spiritual fulfillment too," said Li.

"As the nation's ideas develop in tandem with economic growth, there will be cultural awakening, and people will soon be able to appreciate great architecture."

zhangkun@chinadaily.com.cn

- Online shopping frenzy sparks trash concern

- Is it a thing? 10 odd jobs where you can make good money

- Message on a bottle: Mineral water company launches drive to find missing children

- Snow leopards caught on camera

- A foreigner's guide to Singles Day shopping spree

- China jails 49 for catastrophic Tianjin warehouse blasts

- Americans want to change presidential election system

- UK business calls for exclusive visa system for post-Brexit London

- Australia poised to sign refugee deal with United States: media

- Philippines' Duterte says he is against 2014 defense pact with US

- S.Africa wants to work with US in promoting peace: Zuma

- Trump's victory on global pages

Alibaba breaks sales record on Singles Day

Alibaba breaks sales record on Singles Day

Ten photos from around China: Nov 4-10

Ten photos from around China: Nov 4-10

Snow storm hits Xinjiang

Snow storm hits Xinjiang

Clinton concedes election, urges open mind on Trump

Clinton concedes election, urges open mind on Trump

Places to enjoy golden gingko tree leaves

Places to enjoy golden gingko tree leaves

Taobao village gets ready for shopping spree on 11/11

Taobao village gets ready for shopping spree on 11/11

Overhead bridge rotated in East China's Shandong

Overhead bridge rotated in East China's Shandong

The 75th anniversary of Red Square parade celebrated

The 75th anniversary of Red Square parade celebrated

Most Viewed

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|

Today's Top News

No environmental shortcuts

US election rhetoric unlikely to foreshadow future US-China relations

'Zero Hunger Run' held in Rome

Trump outlines anti-terror plan, proposing extreme vetting for immigrants

Phelps puts spotlight on cupping

US launches airstrikes against IS targets in Libya's Sirte

Ministry slams US-Korean THAAD deployment

Two police officers shot at protest in Dallas

US Weekly

|

|