Taking a tour of the Silk Road

Walking through the exhibition, Yamashita made it clear he values the humanity in his photos, which he describes with an enthusiasm that can almost give the impression that he's seeing them for the first time.

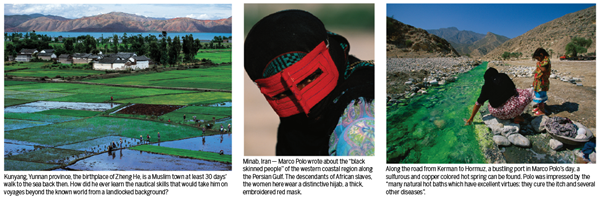

"Photographers are paid to be lucky," he said, revealing the not-so-secret tricks of his trade: get up early, find a great setting and let the "good light" of dawn and dusk do the work.

In one photo, a farmer walks serendipitously into the shot, creating a silhouette against an orange sun reflected on a lake. In another, Xinjiang factory workers pour into street where snow creates an impressionistic effect in black and white. Then a red umbrella opens up, and Yamashita presses the shutter button.

"You have the vision," he said, "then you wait for the moment."

As for China, Yamashita never set out to have one of the world's largest collections of works of the country; he just followed intriguing stories through locales that now would be next to impossible for a foreigner to access in the same way.

He's been working in OBOR countries on and off for the last 30 years.

"It's not like I planned it — ‘Oh, China's going to be great someday and I'm going to cash in,'" he said. "The inspiration or the experience leads to another."

The Carter Center exhibition helped Yamashita see how his work helps China showcase two periods of unique engagement with the globe.

And these historical narratives are gaining steam as China plays a stronger role in regional and global affairs.

"You can see it when they're traveling, there's a confidence there," he said of Chinese tourists and young people. "They're taking an interest in their own history."