'Taken 2' grabs movie box office crown

'Taken 2' grabs movie box office crown

Rihanna's 'Diamonds' tops UK pop chart

Rihanna's 'Diamonds' tops UK pop chart

Fans get look at vintage Rolling Stones

Fans get look at vintage Rolling Stones

Celebrities attend Power of Women event

Celebrities attend Power of Women event

Ang Lee breaks 'every rule' to make unlikely new Life of Pi film

Ang Lee breaks 'every rule' to make unlikely new Life of Pi film

Rihanna almost thrown out of nightclub

Rihanna almost thrown out of nightclub

'Dark Knight' wins weekend box office

'Dark Knight' wins weekend box office

'Total Recall' stars gather in Beverly Hills

'Total Recall' stars gather in Beverly Hills

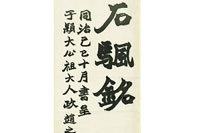

Guardian of time's past

Updated: 2013-01-08 11:09

By Zhao Xu (China Daily)

|

||||||||

|

|

Left and top: Master watch smith Wang Jin labors at his workshop in the Forbidden City. Above: The gilt bronze clock, made in Britain around the mid-18th century, is one of Wang Jin's favorite clocks. Photos Provided to China Daily |

In a quiet corner of Beijing, a watch smith works quietly at restoring life to intricate works of art, accompanied by nothing but his skill and memories. Zhao Xu breaks the reverie to get his story.

For Wang Jin, the best music in the world comes from a tiny little box, and it must be accompanied by the life-affirming tick-tock of mechanical clockwork.

After spending more than three decades restoring antique clocks to their former glory, Wang has become accustomed to an undisturbed life that is as calm as a mirrored pond in a relatively reclusive corner in Beijing's Forbidden City.

But that is what's on the surface.

|

|

Underneath, an accumulation of the concentrated quietness of days and months can lead to a sudden breakthrough, heralded by a chime that seems to rise from the bejeweled gilt chamber of an antique clock to the gray-tiled roofs of the ancient palace.

That's when the thin, slightly pallid man finally sits back, a slight flush on a face worn by fatigue. He can finally lose himself once again in the musical tick-tock of a clock, revived.

"I've never thought about leaving here, not once," Wang says. "This place is where I've spent most of my adult life and it is really all I know."

Outside his little palace-annex-turned workshop, Wang is a taciturn, socially tactless man. At work, surrounded by his gorgeous restorations, he is the absolute monarch, emperor of all he surveys.

Among his most beloved is a sumptuously decorated gilt bronze clock, made in Britain around the mid-18th century. Every one of its three tiers showcases individual wonders.

Wound up, the double doors on the bottom tier slowly swing open to reveal a glistening waterfall, as beautiful tunes play.

The middle tier hints at a more decadent past, with tiny compartments holding everything that might be found in an aristocratic young lady's boudoir: a tiny bottle of perfume, little brushes for applying rouge to dainty cheeks, and even miniature opera glasses for that visit to the theater where both actors on stage and handsome young men in the stalls can be scrutinized.

The top tier is the heart of the timepiece, although it is the least fanciful, and is a clear nod to the owner - the Emperor Qianlong of the Qing Dynasty who reigned between 1736 and 1796. Its whole design is based on a pagoda, complete with a soaring, swirling dragon rendered in abstract form.

As Wang ponders the immense effort that had gone into the mechanics and aesthetics of such a clockwork marvel, he says that the clock collections in the Forbidden City were more about satisfying imagination than measuring time.

"They were the playthings of the emperors and their courtesans," Wang says. "A large part of my job is focused on recreating the wow effect they once had on the beholders."

If polishing off the tarnish of time passed requires hard physical labor, then to solve all the engineering mysteries is sheer mental exercise.

"The Forbidden City holds the world's largest and most extravagant collection of antique clocks manufactured in Europe between the early 18th and 19th centuries. The fact that they were custom-made for the Chinese emperors meant that there is little or no information left in their countries of origin," Wang says.

Most Viewed

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|

Today's Top News

Boston bombing suspect reported cornered on boat

7.0-magnitude quake hits Sichuan

Cross-talk artist helps to spread the word

'Green' awareness levels drop in Beijing

Palace Museum spruces up

First couple on Time's list of most influential

H7N9 flu transmission studied

Trading channels 'need to broaden'

US Weekly

|

|