'Taken 2' grabs movie box office crown

'Taken 2' grabs movie box office crown

Rihanna's 'Diamonds' tops UK pop chart

Rihanna's 'Diamonds' tops UK pop chart

Fans get look at vintage Rolling Stones

Fans get look at vintage Rolling Stones

Celebrities attend Power of Women event

Celebrities attend Power of Women event

Ang Lee breaks 'every rule' to make unlikely new Life of Pi film

Ang Lee breaks 'every rule' to make unlikely new Life of Pi film

Rihanna almost thrown out of nightclub

Rihanna almost thrown out of nightclub

'Dark Knight' wins weekend box office

'Dark Knight' wins weekend box office

'Total Recall' stars gather in Beverly Hills

'Total Recall' stars gather in Beverly Hills

Mystery shrouds art sales

Updated: 2013-02-04 16:34

By Robin Pogrebin (China Daily/Agencies)

|

||||||||

|

|

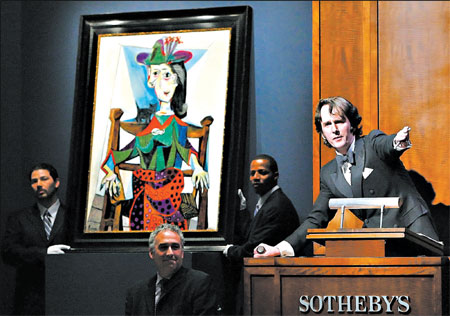

Some say the art market needs closer monitoring, especially its bidding process. Art being sold at a Sotheby's auction in 2006. Peter Foley / European Pressphoto Agency |

When some of the world's richest people gather for the glittering New York auction season this spring, they will spend hundreds of millions of dollars in an art market that allows opaque transactions and has few outside monitors.

At major auctions the first bids announced for a piece are typically fictional - numbers pulled from the air by the auctioneer to jump-start bidding.

Under a practice called third-party guarantees, collectors can find themselves being bid up by someone who, in exchange for agreeing in advance to pay a set amount for a work, is promised a cut of anything that exceeds that price.

And year round, galleries ignore with impunity a 42-year-old law that says they must post their prices. Art sales in New York, at galleries or at auction, are estimated at $8 billion a year. Many in the art world insist there is no need for further scrutiny of a market that prompts few consumer complaints and is vital to the New York economy. But other veterans of the business say monitoring has not kept pace with the increasing treatment of art as a commodity.

"The art world feels like the private equity market of the '80s and the hedge funds of the '90s," James R. Hedges IV, a New York collector and financier, said. "It's got practically no oversight or regulation."

For two decades some New York State lawmakers have been trying to curb chandelier bidding, a bit of art-market theater in which auctioneers begin a sale by pretending to spot bids in the room. In reality the auctioneers are often pointing at nothing more than the light fixtures.

"The time has come to give up this fiction that there are actual real bidders," said David Nash, a gallery owner.

|

|

Jennifer S. Altman for The New York Times |

Some say that, given the money involved and the number of newly wealthy buyers, stricter rules are a must. But attempts in the State Legislature to ban the practice have failed. The law says auctioneers can announce such bids as long as they stop before reaching a sale item's reserve price, the confidential minimum amount that sellers have agreed to accept.

Auction officials say most criticism of their practices comes from gallery owners - their rivals for sales - who they say operate without oversight.

"The dealers are not regulated at all," said Patricia G. Hambrecht, chief business development officer for the Phillips auction house.

Some perceptions of the market as an insiders' game stem from recent lawsuits against galleries, including three by collectors who accused Knoedler & Company, now defunct, of fraud.

Perhaps nothing illustrates the art market's laissez-faire spirit better than the way galleries flout New York City's "truth in pricing" law. It says items for sale must have a price tag conspicuously displayed. None of 10 galleries visited at random in January had posted prices, though a few smaller ones produced price lists when asked. In 1988 Consumer Affairs officials cracked down on galleries that did not post prices, but there does not appear to have been a similar effort in recent years.

Dealers said posting prices on valuable works in an open gallery creates security concerns and disrupts an exhibition's aesthetics by transforming artworks into commodities. "We consider it tacky to do that," Richard L. Feigen, a longtime dealer, said.

Galleries, experts say, often choose to whom they will sell and favor good customers, especially those whose ownership will add luster to an artist's market standing.

"You can't deny someone the opportunity to buy something if the price is posted and the work is unsold," said Robert Storr, dean of the Yale University School of Art. "Unless there is the will to enforce these things," he said of pricing laws, "there is no point in having them."

But when you talk to dealers about what most needs policing in the art market, many mention third-party guarantees.

Under the practice, Christie's sold Picasso's "Nude, Green Leaves and Bust" in 2010 after it found a third party willing to put up an undisclosed guarantee in exchange for a cut if it sold above that amount. When the painting, with a low estimate of $70 million, sold for $106.5 million - at the time, the highest price ever for a work sold at auction - the guarantor presumably walked off with a good bit of money.

Critics argue that the guarantors have an undisclosed interest in the outcome and an unseen advantage over other bidders because a buyer who wants the work might wind up competing against someone who only wants to bid up the price to increase his cut.

"In a market that purports to be transparent and offering disclosure of conflicts of interest, this is not a level playing field," said Mr. Hedges, the collector.

At Christie's and Phillips, both large auction houses, even if a guarantor ends up owning the work, he would still pay less for it than anyone else. For example, if a guarantor's bid of $12 million turned out to be the winning bid, the guarantor would not pay the full $12 million because he or she still gets the cut - called a financing fee - of any amount above the $10 million guarantee. That means the prices in auction records - the industry's prime metric for measuring value - are not always accurate.

"If the price is not the price because the guarantor has bought it and gotten a discount, there is no longer any transparency in the market," said Michael Moses, a retired New York University professor whose company, Beautiful Asset Advisors, tracks the art market.

In 1991, when he was a New York State assemblyman, Richard L. Brodsky introduced a bill to ban chandelier bidding.

The consumer affairs agency backed him, saying the practice may inflate prices by snaring "unwitting bidders into thinking that they are competing with other potential purchasers."

But auctioneers say chandelier bidding is necessary to keep the reserve secret and protect the seller. Without it, they say, bidding might end up starting at the reserve, since that is the minimum a seller will accept, and thus telegraph what it is.

Christie's and Sotheby's hired Stanley Fink, a powerful former Assembly speaker, to lobby on their behalf, and the bill has yet to become law. But its most recent Senate sponsor, Daniel L. Squadron of Manhattan, has not lost hope that the legislation might pass.

"The need to trust the credibility of an auction," he said, "is as real a need as it was 20 years ago."

The New York Times

Most Viewed

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|

Today's Top News

Boston bombing suspect reported cornered on boat

7.0-magnitude quake hits Sichuan

Cross-talk artist helps to spread the word

'Green' awareness levels drop in Beijing

Palace Museum spruces up

First couple on Time's list of most influential

H7N9 flu transmission studied

Trading channels 'need to broaden'

US Weekly

|

|