'Taken 2' grabs movie box office crown

'Taken 2' grabs movie box office crown

Rihanna's 'Diamonds' tops UK pop chart

Rihanna's 'Diamonds' tops UK pop chart

Fans get look at vintage Rolling Stones

Fans get look at vintage Rolling Stones

Celebrities attend Power of Women event

Celebrities attend Power of Women event

Ang Lee breaks 'every rule' to make unlikely new Life of Pi film

Ang Lee breaks 'every rule' to make unlikely new Life of Pi film

Rihanna almost thrown out of nightclub

Rihanna almost thrown out of nightclub

'Dark Knight' wins weekend box office

'Dark Knight' wins weekend box office

'Total Recall' stars gather in Beverly Hills

'Total Recall' stars gather in Beverly Hills

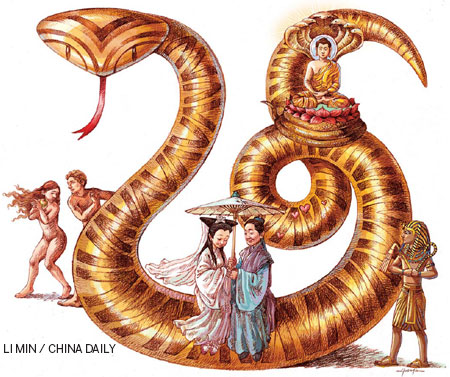

Great snakes!

Updated: 2013-02-08 09:11

By Raymond Zhou (China Daily)

|

||||||||

Despite its fearsome reputation, the representation of the zodiac creature includes a bittersweet tale of broken hearts and love transcending disaster.

Let's face it, the snake has an image problem. In preparation for the Year of the Snake, a mammoth decoration in the form of the reptile was erected at a highway toll plaza in Sichuan province. Somehow, they gave the snake the countenance of a chicken. Onlookers joked that whoever sculpted it must have been born in the Year of the Rooster, and others chimed in that they would no longer be afraid of the snake now it had taken the shape of a friendlier animal.

On these occasions, Chinese people have traditionally resorted to euphemisms to represent the snake in an auspicious light. The dragon, a symbol of power and majesty, is often used to stand in for its earthbound peer; hence the term "the little dragon".

Efforts to distinguish the two have been unceasing, as is evident in such catchphrases as "an assortment of dragons and snakes", meaning people of different qualities and status sharing one space, and "dragons withdrawing and snakes expanding", meaning good guys lying low and bad elements strutting their stuff. It is futile to pass off snakes as dragons.

In China, snakes are predominantly associated with venom - even though only 65 species out of some 600 in the country are poisonous. Worldwide, there are 725 species of venomous snakes, of which about 250 can kill a human.

It is said the venom from the bite of a Russell's viper can cause its victim to drop dead before he or she can walk seven steps. The Chinese call it the "Seven-Pacer".

Otherwise, if you're bitten by a snake - and it's not one of the 250 lethal species - there's a good chance you'll tremble at the sight of a rope, or anything vaguely resembling a snake, for the rest of your days.

There is an ancient tale of a man who spots a snake in his glass of liquor. It turns out the wriggly thing was the reflection of a bow hanging on the wall. The yarn has since been immortalized as a phrase for unfounded panic.

Contrary to some cultures where the snake is perceived as a steadfast defender, in the Chinese one it is enshrined as an object of fear, except perhaps in calligraphy, where the serpentine brush stroke depicting a snake flying or scurrying away is to be marveled, not quivered, at.

Very often, the snake comes with its nobler peer, the dragon, in such portrayals. However, one ancient calligrapher painted a realistic snake on a scroll, and then, out of a whim, added a foot. Some species have a pair of vestigial claws, but in this instance, it's the painter, not the snake, who is the butt of derision.

For all its snake-related idioms, China does not hold a candle to Indian mythology when it comes to snake references. Likewise, Egyptian, Greek, Christian and many other cultures have images of the snake more colorful than ours.

The Chinese snake is not as rich in connotation and has not spilled over into the visual arts. We do not have a deity sitting on a coiled python; the Buddhist concept of reincarnation has not been compared to the shedding of a snake's skin; our female monsters do not sport a crop of snakes for hair; and a snake is not the cause for carnal temptation.

Then again, Nuwa, the Chinese goddess who mended the broken sky, has a human head and a snake body. And in the 16th century classic Journey to the West, a.k.a. The Monkey King, there is a nine-headed snake.

While overwhelmingly repulsed by the snake, Chinese sentiments for the 2013 zodiac animal can be more complex, varying in time and locality. In Fujian province, the snake is held in a god-like position. It is not to be killed if found in a home, but removed gently back to the wild. It is definitely not to be eaten.

And at a mid-year festival, a parade is organized in which every participant holds a snake, which is supposed to bring them peace and harmony.

A branch of the Li ethnic group in Hainan province regards the snake as their ancestor. There are several folk tales of humans and snakes marrying each other. If a snake is found near a tomb, it is considered the apparition of the dead person.

In Guizhou province, the Dong ethnic costume features myriad snake motifs, and they even incorporate snake-like moves in their prayer ritual.

But mostly, after thousands of years, the snake has been demonized beneath the glossy veneer of civilization. In many cases, it has either morphed into the more auspicious dragon or simply become an embodiment of malice and immorality.

One similarity remains between East and West, though - the snake as a symbol of sexual passion. In China, snake wine, made by infusing snakes in grain alcohol, is believed to have a rejuvenating, sometimes aphrodisiac power.

As a gourmet dish, the snake is much valued in the Middle Kingdom, especially in southern China. For those who believe in traditional Chinese medicine, each part of the snake is a "treasure". Snake bile is said to be a remedy for many ailments, including rheumatism. Ironically, its venom is made into drugs to counter pain, poisoning and blood clots.

A decade ago, there was a zoo in a suburb of Guangzhou that was devoted to snakes. As a publicity stunt, the owner put his daughter into a cage with hundreds of snakes, where she stayed long enough to break the Guinness World Record.

Afterwards, a group of local celebrities were invited to a banquet, where a dozen courses were served, each one a dish of snakes but cooked in different ways. I tagged along, swearing I would never touch or eat a snake. But out of courtesy to the host, I broke my vow. It turned out snakes are not that delicious, at least to me. The meat was tough and chewy, nowhere near as tasty and delicate as eels, which friends said I should pretend they were.

The most famous Chinese legend involving snakes puts a decidedly positive spin on their portrayal. Madame White Snake has been told in many operas, movies and television serials. The spirit of a white snake transforms herself into a beautiful maiden, Bai Suzhen, who falls in love with Xu Xian, a mortal living by Hangzhou's scenic lake.

They get married, but before they can live happily ever after, a monk named Fahai, who used to be a tortoise spirit, tricks Xu into coercing his wife to drink wine, which reveals her true form as a snake. Xu Xian is so scared that he falls ill, but Bai flies to Mount Emei and steals a medicinal herb that revives her husband.

Still untrusting of his wife, Xu allows himself to be taken by Fahai to his temple in Zhenjiang. Bai and her maid, or younger sister as some legends say, who is a green snake spirit, come to the rescue. They use their magic power to whip up a flood. As Bai is pregnant, her power is limited and fails to save him.

The month after she gives birth, Bai is captured by Fahai and suppressed under the weight of the Leifeng Pagoda. When her son grows up, he comes to pray for his mother and topples the tower, and they are reunited.

The power of love to transcend species lies at the core of this myth, which has countless variations. In all versions I've seen, the white snake is a symbol of purity, and the green snake one of loyalty. The human is weak-willed and the tortoise represents a force against love and compassion.

However, research showed that, at the root of the oral tradition, the snake spirits began as demons of temptation and deceit, and the monk a savior. Over the centuries, this horror story morphed into an ethereal romance, with the good and bad roles reversed.

Maybe, given time, we can celebrate the Year of the Snake with an upbeat interpretation of the animal that incorporates our modern sensibilities. Maybe the snake can at once charm and be charmed. Maybe it can be a python of Herculean strength and courage

Forget about that. The snake in Chinese incarnations will always remain female. You know what? Snake in pinyin is she. I heard that's the reason the Taiwan girl band S.H.E. was invited to the 2013 New Year's Eve gala on national television.

raymondzhou@chinadaily.com.cn

(China Daily 02/08/2013 page24)

Most Viewed

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|

Today's Top News

Boston bombing suspect reported cornered on boat

7.0-magnitude quake hits Sichuan

Cross-talk artist helps to spread the word

'Green' awareness levels drop in Beijing

Palace Museum spruces up

First couple on Time's list of most influential

H7N9 flu transmission studied

Trading channels 'need to broaden'

US Weekly

|

|