'Taken 2' grabs movie box office crown

'Taken 2' grabs movie box office crown

Rihanna's 'Diamonds' tops UK pop chart

Rihanna's 'Diamonds' tops UK pop chart

Fans get look at vintage Rolling Stones

Fans get look at vintage Rolling Stones

Celebrities attend Power of Women event

Celebrities attend Power of Women event

Ang Lee breaks 'every rule' to make unlikely new Life of Pi film

Ang Lee breaks 'every rule' to make unlikely new Life of Pi film

Rihanna almost thrown out of nightclub

Rihanna almost thrown out of nightclub

'Dark Knight' wins weekend box office

'Dark Knight' wins weekend box office

'Total Recall' stars gather in Beverly Hills

'Total Recall' stars gather in Beverly Hills

Crowd pleaser

Updated: 2013-05-17 10:52

By Hu Haidan (China Daily)

|

||||||||

While pursing her master's degree at Columbia, Lu enjoyed a life away from music.

Last fall and winter, she got the idea for planning her own concert.

Lu had been selected as a production assistant for an off-Broadway revival of Golden Child, by Chinese-American playwright David Henry Hwang.

"The most important thing I learned from that experience is how to make a show work from the very beginning," she says.

At a meeting to celebrate the show's success, Lu brought along her yangqin and played for members of New York's Signature Theater Company.

"People applauded for a long time," she recalls. "They told me they loved my performance and they said I should hold my own concert."

Lu figured it was time to apply the knowledge she had gained after more than two years in the United States. The planning began.

"I started contacting different concert halls and trying to raise money for my concert. I did face a lot of difficulty in making it finally happen, but it was definitely worth it."

By the time Tuesday night's concert at Weill Recital Hall was over, Lu felt she had left an impression on the audience, who gave her a standing ovation. "I am one step closer to my dream," she says. "The experience here has brought me to a new level of making this traditional Chinese instrument known to a Western audience."

The ambitious musician wasn't content to stop at Carnegie Hall, however. Her calendar has three other concert dates this month, the next is on May 19 when she will perform at a benefit in New Jersey for victims of the April 20 earthquake in Lushan, Sichuan province, that killed almost 200 people.

Lu is also looking for opportunities to collaborate with Eastern and Western musicians.

It is believed that China adapted the dulcimer over 400 years ago in the days of the Silk Road trading route. The yangqin's primacy in Chinese classical music is akin to the role of the piano in Western music. The Chinese instrument is performed either solo or with the erhu, pipa (both stringed) and flute-like dizi.

|

|

|

|

China National Ballet performs at Beijing Institute of Fashion Technology |

Troubled prodigy |

Most Viewed

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|

Today's Top News

Shenzhou X astronaut gives lecture today

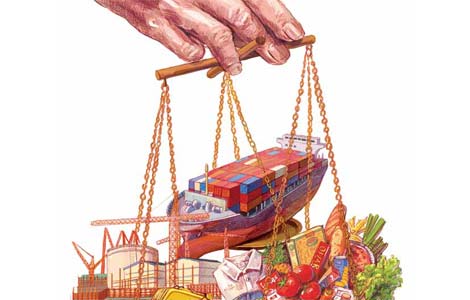

US told to reassess duties on Chinese paper

Chinese seek greater share of satellite market

Russia rejects Obama's nuke cut proposal

US immigration bill sees Senate breakthrough

Brazilian cities revoke fare hikes

Moody's warns on China's local govt debt

Air quality in major cities drops in May

US Weekly

|

|