Linking birdsong and baby talk

Updated: 2013-07-14 08:06

By Tim Requarth and Meehan Crist (The New York Times)

|

||||||||

Babies learn to speak months after they begin to understand language. As they are learning to talk, they babble, repeating the same syllable ("da-da-da") or combining syllables into a string ("da-do-da-do").

But when babies babble, what are they doing? And why does it take them so long to speak?

A surprising source is now providing some answers: songbirds.

Researchers who focus on infant language and those who specialize in birdsong have published a new study suggesting that learning the transitions between syllables is the crucial bottleneck between babbling and speaking.

"We've discovered a previously unidentified component of vocal development," said the lead author, Dina Lipkind, a psychology researcher at Hunter College in Manhattan. "What we're showing is that babbling is not only to learn sounds, but also to learn transitions between sounds."

The results provide insight into language acquisition and may eventually help illuminate human speech disorders. At first, however, the scientists behind these findings were studying birds.

"When I got into this, I never believed we were going to learn about human speech," said Ofer Tchernichovski, a birdsong researcher at Hunter College.

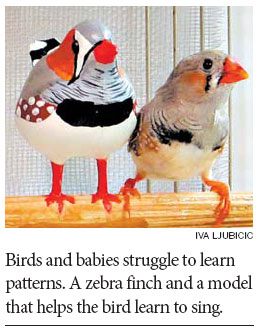

He and Dr. Lipkind were teaching young zebra finches in soundproof boxes to switch the order of syllables in their songs. The birds could learn a new song only after practicing thousands of times a day for weeks. The roadblock seemed to be the transitions, as only the syllable order was changed.

Their collaborator Kazuo Okanoya, then at the Riken Brain Science Institute in Japan, saw the same effect in Bengalese finches, which were living in a more natural environment, in large aviaries full of other finches.

Dr. Tchernichovski and Gary Marcus, who studies infant language learning at New York University and who helped design the study, discussed the results in relation to human infants.

They found that as babies learn a new syllable, they first tend to repeat it. Then, like the birds, they begin appending it to the beginning or end of syllable strings, eventually inserting it between other syllables.

As with the birds, learning the transitions between new and old syllables is a painstaking process for babies. That could help explain why children continue to babble even as they begin to understand language.

This study may also rekindle a debate over whether birdsong can be used to learn about human speech. The two may seem to have little in common, but recently, researchers have found many parallels.

Birds and humans share molecular building blocks - including the FOXP2 gene, which made a big splash a decade ago when it was identified as the gene responsible for one human family's mysterious speech disorder.

We seem to share brain structures crucial for song and speech, and both make phrases out of "syllables." Both also "babble" during a critical learning period; and both are "vocal learners," learning to sing or speak from a tutor or parent.

With these parallels in mind, researchers are turning to birdsong as a model for human speech which is difficult to study. Vocal learning is rare among animals; not even humans' closest evolutionary relatives do so.

Songbirds do. And researchers can do experiments with birds that they can't do with humans. As Dr. Lipkind put it, "You can't put babies in soundproof boxes."

Sarah Woolley, a birdsong researcher at Columbia University in New York, agreed that the links were intriguing. "No one is saying birdsong is language," she said. "But there are so many parallels. We've got this opportunity to model vocal learning by testing how the rules work for birds and making predictions about how humans learn."

But others question whether birdsong can ever really tell us much about human language. Still, songbird researchers are hopeful.

"Roundworms are pretty evolutionarily distinct from humans, too," said a birdsong expert, Daniel Margoliash, of the University of Chicago. "I don't know about you, but when I look at a roundworm I don't think: 'Ah! Just like little Jimmy!' And yet they're a useful system."

The New York Times

(China Daily 07/14/2013 page11)

Victoria Beckham S/S 2014 presented during NYFW

Victoria Beckham S/S 2014 presented during NYFW

'Despicable' minions upset Depp's 'Lone Ranger' at box office

'Despicable' minions upset Depp's 'Lone Ranger' at box office

'Taken 2' grabs movie box office crown

'Taken 2' grabs movie box office crown

Rihanna's 'Diamonds' tops UK pop chart

Rihanna's 'Diamonds' tops UK pop chart

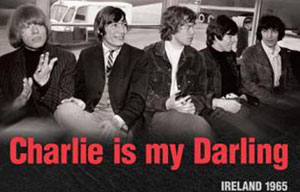

Fans get look at vintage Rolling Stones

Fans get look at vintage Rolling Stones

Celebrities attend Power of Women event

Celebrities attend Power of Women event

Ang Lee breaks 'every rule' to make unlikely new Life of Pi film

Ang Lee breaks 'every rule' to make unlikely new Life of Pi film

Rihanna almost thrown out of nightclub

Rihanna almost thrown out of nightclub

Most Viewed

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|

Today's Top News

Going green can make good money sense

Senate leader 'confident' fiscal crisis can be averted

China's Sept CPI rose 3.1%

No new findings over Arafat's death: official

Detained US citizen dies in Egypt

Investment week kicks off in Dallas

Chinese firm joins UK airport enterprise

Trending news across China

US Weekly

|

|