Reading the stars

Updated: 2014-12-10 07:26

By Zhao Xu(China Daily)

|

||||||||

In his first book, Chinese author Wang Wei examines how astrology shaped Western culture, Zhao Xu reports.

No author wants readers to toil through an entire book only to find that they've been somehow cheated, believes amateur English linguist Wang Wei.

"But for me, a staunch agnostic who has decided to take on the subject of astrology, this is more or less unavoidable," Wang, 35, says of his first book, Words from Stars.

|

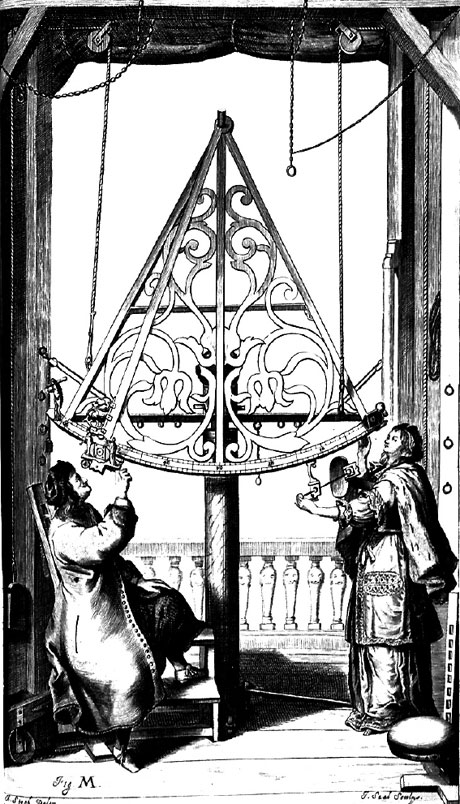

A 17th-century Dutch print depicting astronomical observations with a giant sextant. Provided to China Daily |

The title of the recently published work is meant to call to mind the South Korean TV series My Love From the Star, which became an instant hit with millions of Chinese after it was aired here.

The series also indirectly helped the sale of products such as Hermes handbags and YSL lipstick that the actresses used, but more importantly, it created more interest in astrology in China.

Wang says he hoped to build on that opportunity while writing the book.

"People will find out my true thoughts on astrology, but not before they have familiarized themselves with its origin in ancient Greek and Roman culture, as well as its evolution in Europe through the Middle Ages, the Enlightenment, until the years preceding World War I," he tells China Daily.

His interest in the study of astrology grew from his curiosity about Western history and culture. "You look at the development of Western culture closely and you realize the vital role science has played. And then when you trace science back to its roots, you discover astrology among other things," Wang adds.

The astrological culture first germinated in Mesopotamia in western Asia, which includes today's Iraq, parts of Turkey and Syria, and it later went to the West, he says, adding that the ancient culture also found echoes in China, in the form of oracle bones that appeared a few hundred years later during the Shang Dynasty (c.16th century-11th century BC).

Astrology and astronomy

An avid researcher of etymology, Wang entertains himself by examining the long-buried connection between a primitive obsession with the unknown and the modern English language.

One example, he cites, is the English word "disaster", in which "di" means "absence or removal" and "astor" is the Latin word for star.

"Imagine that people long ago gazed at the night sky and were panicked by the sudden disappearance of a familiar star. Luckily for them, they didn't have smog back then," Wang says.

According to him, the influence astrology has had on Western culture can be understood by looking up the many English words that were derived from heavenly bodies.

In his book, Wang also focuses on the tension and interplay between astrology and astronomy, with the latter being venerated today as science.

"To put it simply, astronomy rose from astrology to become its most powerful counterforce," says Wang. Back in the 15th and 16th centuries, the pioneers of modern astronomy - from Nicolaus Copernicus to Galileo Galilei - invariably had a sincere interest, if not belief, in astrology, he adds.

Galilei, who believed in heliocentrism (sun at the center of the solar system), first proposed by Copernicus, made enemies in the Roman Catholic establishment because of his scientific approach to the universe, but that didn't prevent him from having a horoscope cast for his newborn daughter.

"Iconoclastic as their theories were, these early astronomers didn't sever themselves from the ancient beliefs of their ancestors," Wang says, adding that some of the data they used to draw their conclusions had been recorded by generations earlier.

In his book, he writes, astrology saw its reputation dented in the Age of Enlightenment in the 18th century, when intellectuals in western Europe began to promote the idea of reason over norm, but it made a recovery in the next century following a long spell of peace on that continent. In the first half of the 20th century, astrology started to bloom in popular Western culture.

Mass media played a major role in promoting astrology, Wang says. R. H. Naylor, a British astrologer, started a newspaper column on the subject that was widely read, laying the ground for all major European and US newspapers to follow suit.

"From simple to complicated and then back to simple - that's the trajectory astrology has taken in the past few centuries," Wang continues. Before Naylor, various people had sought to do subtraction with astrology, but the Briton made the most drastic paring-down by focusing on the sun and disregarding all other components, he says.

This highly accessible version of astrology, known as sun-sign astrology, is the one most of us know today, although traces of ancient Greek culture can still be found.

Reliability vs superstition

In his book, the author writes, among the 12 star signs popular today is cancer, or the crab, but people wonder why it is called such. When a surgeon in ancient Greece first noticed cancerous tumors in a patient, he thought the distorted blood veins appeared like the legs of a crab, and he named the tumor "cancer", old Greek for crab.

But the one question that many people ask: Is astrology reliable? Or, is it pure superstition?

"As far as I can see, modern astrology has grown into a belief system; it has a hold on people's minds, and defies any attempts to prove or disprove it," he says. "During the Renaissance, many popes and cardinals regularly consulted astrologers. And neither the Enlightenment nor the development of modern astronomy could seriously threaten its existence. Why? Because a fascination with the starry sky has become part of human consciousness."

"For many Chinese, modern astrology has a particular pertinence since it enables them to discuss their private feelings in a way traditional Chinese culture does not encourage," Wang says.

Back in 1930, Naylor forecasted that "a British aircraft will be in danger". And when an airship duly met its unhappy end a few weeks later, Naylor and astrology became the talk of the town. "However, if you take into account the frequency of such incidents in the days of early aviation, Naylor might have been admired for his statistical insights rather than prophetic powers," he adds.

Contact the writer at zhaoxu@chinadaily.com.cn

(China Daily 12/10/2014 page20)

Most Viewed

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|

Today's Top News

Don't ignore own culture for Xmas, schools tell students

Christmas a day for Chinese food in US

China urged to tap Canada's talent

Research center honors late translator

Chinese dancer joins Nutcracker

Beauty firm's business not pretty in China

Reform set for GDP calculation

'Anti-graft' fight is hottest online topic

US Weekly

|

|