Saving the fabric of history

Updated: 2015-08-22 04:50

By ZHANG KUN in Shanghai(China Daily USA)

|

||||||||

|

Before Before |

|

This painting was a badly damaged portrait of ancestors where the head of one of the subjects was missing. The restorer, Yan Xiaoyan, had to intensively study the art of ancestor portraits, a popular genre of painting, before coming up with a plan to fill in the missing head. provided to China daily |

Between June 23 and July 17, Jianyu Yaji — a gallery in Hongqiao Antique Town in western Shanghai — became a bustling hub of international art exchange as it hosted an exhibition featuring Chinese paintings and calligraphy works that were restored and reproduced by 32 graduates hailing from the restoration department of the College of Fine Arts in the Shanghai Institute of Visual Arts (SIVA).

The exhibition had attracted scholars and academics from some of the most acclaimed museums in the world, including researchers and restoration experts from the British Museum in London, the Metropolitan Museum in New York and the Shanghai Museum. But besides being a platform for showcasing works of art, the exhibition also earned several graduates opportunities to work abroad at the famous Metropolitan Museum.

“They have interviewed three of our students, and the next round of interviews will take place in the United States. It’s an extremely competitive process, and everything is fair and open,” said Shen Yazhou, a professor at SIVA who was once a restorer at the Shanghai Museum.

Chinese art, especially traditional ink paintings, are gaining more recognition in the international art scene as China’s economy and social development grow, observed Qu Jiping, manager of Jianyu Yaji gallery. In the past few years, when turbulence in the financial markets significantly impacted the price of contemporary art, the value of Chinese art and antiques have remained steady at auctions home and abroad, he said.

The intricate handicraft of restoration is an indispensable part of China’s art history but has in the past few decades, like many other traditional professions, been left behind in the wake of societal change. The restoration of ancient Chinese art has been an expertise passed down from one generation to another through family-size studios. Two ancient water towns in Suzhou and Yangzhou, Jiangsu province, had both hosted some renowned studios in the early 20th century and when the Shanghai Museum was founded in the 1950s, experienced craftsmen from these places were recruited.

Shen, who was a young apprentice at Shanghai Museum during the 1970s, learned from these experienced craftsmen and he still remembers the heated arguments between the masters of “Yangzhou school” and “Suzhou school”. It was only a few years later that he realized this bickering was actually an important academic discussion about the best methods to create art.

In an attempt to integrate traditional handicraft into its modern curriculum, SIVA founded the restoration department at its College of Art in 2008 and hired Shen along with other experienced restorers as professors. The new curriculum now requires students to learn the science and artistic theory involved in restorations, as well as the actual operation methods. One of the most important guidelines in art restoration is that the work must be retrievable so that it can be further restored in the future when better technologies are available.

“They have to practice traditional ink painting skills, learn modern laboratory technologies and of course the modern research methodology and thesis writing. This systematic education will teach not only how the job is done, but also why it should be done this way,” said Shen.

As Chinese paintings or calligraphy works are usually mounted for the purpose of visual appreciation as well as conservation, a layer of rice paper or silk needs to be glued to the back of the artwork before a frame is added. However, as time passes, the paper or silk backing inevitably gets worn out. Also, mineral pigments and ink traditionally used in Chinese art easily dissolves in water, but restoration works cannot be performed without water. Shen said that it requires a lot of experience to tell which painting should be soaked in water for some time, and which should just have water sprinkled on the surface.

After a preliminary evaluation of the condition of the artwork, the restorer proceeds to carefully rearrange the fibers and remove the dirt and mold with fine tools. Following these cleaning procedures, restorers then separate the painting or calligraphy from the protective lining and use all possible means to mend the damaged areas. The whole process is akin to putting together an incredibly delicate jigsaw puzzle, because traditionally handmade rice paper and silk consist of very fine fibers.

“You must also use all means possible to achieve the same shade of color as the original,” said Fang Jinjie, a new SIVA graduate whose restored artworks were on exhibition.

Sun Jian, a senior restorer with Shanghai Museum, used to apply tobacco ashes on the paper in order to achieve the right color. Fang had also tried using grounded brick powder before.

Among the artworks on exhibition was a badly damaged portrait where one of the subjects was missing a head. There was also a painting that was restored from hundreds of torn pieces, and another that was damaged during the Cultural Revolution (1966-1976) after the Red Guards defaced the work — the painting of ancestors was considered “counter-revolutionary” — by drawing a cross on it. Fortunately the cross was not painted across the body of work, else the restoration process would have been much more complicated, Fang said.

Restorers are permitted to fill in the missing strokes in a damaged painting or calligraphy work, but only those who possess a deep understanding of the work and its intended message are trusted with such work. Yan Xiaoyan, for example, had to intensively study the art of ancestor portraits, a popular genre of painting, before coming up with a plan to fill in the missing head in the portrait she restored.

The restoration department in SIVA enrolls up to 20 students every other year. Only a few institutes in China provide higher education programs for the restoration of ancient Chinese art and SIVA stands out among them largely because of the expertise from Shanghai Museum, whose restoration department is among the most recognized in China alongside Beijing’s Palace Museum.

zhangkun@chinadaily.com.cn

- Tsipras formally resigns, requesting snap general elections

- China-Russia drill not targeting 3rd party

- UK, France boost security

- China demands Japan face history after Abe's wife visits Yasukuni Shrine

- DPRK deploys more fire units to frontlines with ROK

- DPRK, ROK trade artillery, rocket fire at border

Across America over the week (Aug 14 - Aug 20)

Across America over the week (Aug 14 - Aug 20)

Stars in their eyes: leaders in love

Stars in their eyes: leaders in love

A survival guide for singles on Chinese Valentine’s Day

A survival guide for singles on Chinese Valentine’s Day

Beijing police publishes cartoon images of residents who tip off police

Beijing police publishes cartoon images of residents who tip off police

Rare brown panda grows up in NW China

Rare brown panda grows up in NW China

Putin rides to bottom of Black Sea

Putin rides to bottom of Black Sea

The changing looks of Beijing before V Day parade

The changing looks of Beijing before V Day parade

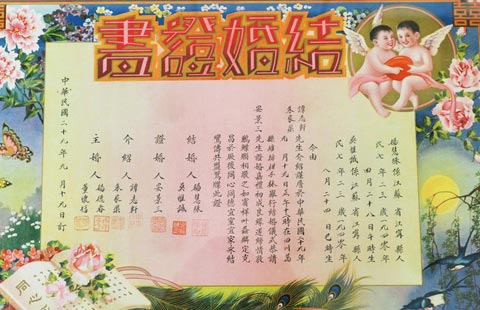

Nanjing displays ancient marriage, divorce certificates

Nanjing displays ancient marriage, divorce certificates

Most Viewed

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|

Today's Top News

Emissions data won't change China policy

Preparations shutter Forbidden City, other major tourist spots

President Xi Jinping calls for crews not to ease up

Chemical plants to be relocated in blast zone

Asian sprinters on track to make some big strides

Jon Bon Jovi sings in Mandarin for Chinese Valentine's Day

Tsipras formally resigns, requesting snap general elections

DPRK deploys more fire units to frontlines with ROK

US Weekly

|

|