Met showcases China's rich history in print

Updated: 2012-06-22 12:46

By Kelly Chung Dawson in New York (China Daily)

|

||||||||

The modern perception of China as more copycat than innovator is belied by a check of game-changing Chinese inventions through the centuries - the compass, gunpowder, papermaking and the printing arts.

A new exhibition at New York's Metropolitan Museum of Art surveys the last of these, particularly its transformative power in disseminating information.

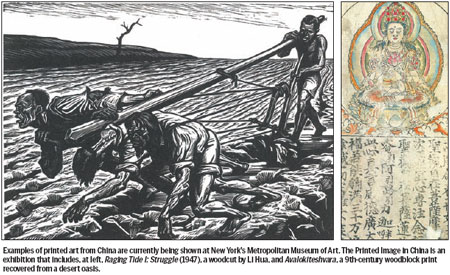

The Printed Image in China, 8th-21st Century features over 140 printed images created through a technique that first spread in China around AD 700 as a tool for reproducing Buddhist texts.

"China is the country with the longest print history in the world," British Museum curator Clarissa von Spee told China Daily. "It's just amazing the scope and continuous practice of printing there. I am hoping that this exhibition will help people understand how important printing was to world culture in general.

"In fact, China actually has a remarkable history of inventions and artistic creativity," she said.

Mike Hearn, curator of Asian art at the Metropolitan Museum, speculates that China's lack of exposure to other nations led to stunted progress after its initial flurry of innovation.

"I think that in the West you had a number of competing cultures vying for colonial control, or warfare or shipping control, and that competitive environment was less present in China because it was already the largest nation-state in the world for much of its history," he said.

"There wasn't that sense of international competition that fueled the Renaissance and Enlightenment in Europe."

The Met show, which runs through July 29, traces the spread of printmaking, first through the use of woodblock printing and later using Western techniques of engraving and lithography. A number of wooden blocks used for printing are also on display.

Most of the exhibition comes from the British Museum, which is widely recognized as having the world's most comprehensive print collection.

"To collect something like this to this extent is to truly reflect on the evolution of the craft and art form," Hearn told China Daily. "The British Museum has conscientiously built their collection to understand how printing has evolved and how it reflected the changing priorities of society over time. For me, it's one of the most exciting exhibits we've ever had because of the quality and comprehensiveness. We really get a sense of this artistic medium's evolution over a thousand years."

The venerable London institution's extensive holdings are the product of its founder's foresight. Sir Hans Sloane (1660-1753) began collecting prints during his lifetime, not necessarily for their artistic value but due to his interest in botany, religion and culture, Hearn said.

The collection is unusual, as most Western museums have prioritized painting and sculpture, von Spee explained.

"Printing has always been a bit undervalued, and in China you can say the same," she said. "Printed images were never considered artistic; they were considered functional."

Of course, in the beginning the invention of carved woodblocks to propagate Buddhist texts was practical, a means of eliminating scribal error and reducing the time needed for labor-intensive hand-copying. A number of those religious prints are on display in the first of eight rooms in the Met's exhibition, which is organized by theme and chronology (reflecting the evolving function of print over time). As a result, the prints move in purpose from religious and didactic to a form of pop culture and eventually to serving a purely artistic purpose.

Although color woodblock printing is most often associated with Japan, the technique originated in China and spread outward later, Hearn said. The exhibition includes examples of Japanese prints that were clearly inspired by earlier Chinese work. Later, when outside work filtered back into China, Chinese printmakers were also inspired.

In fact, this cross-pollination of influences was a major factor in the development of printmaking, Hearn said.

For example, the Qing Dynasty Emperor Kangxi (1654-1722) commissioned Jesuit missionaries to create copperplate engravings of his summer palace. Chinese artists first painted the scenes, and Western artists translated the paintings into engravings in the Western style. In 1724 the Italian Jesuit priest Matteo Ripa brought those engravings back to London, where a man named William Kent saw them. Kent eventually became the most important advocate of naturalistic landscapes in British gardening, an influence heavily shaped by his exposure to the Chinese garden engravings, Hearn said.

"That was one of the important vehicles of the Enlightenment, when this idea of naturalistic landscapes was introduced in Europe," Hearn said.

In the 18th century, Emperor Qianlong (1711-1799) commissioned Jesuit priests to design European-style gardens at his palace, which were also depicted in Western-style engravings at the time.

Another set of engravings included in the Met show depicts various historical battles, commissioned by Qianlong. The early engravings employ Western-style depiction, but the final one in the series is a beautifully rendered Asian style representation scene that echoes classic Chinese painting.

"It's really exciting to see how the technology of printing was influenced by cross-cultural mixing," he said. "I think the Europeans were influenced by Chinese content, and the Chinese were influenced by Western techniques."

Later prints in the exhibition include modern cigarette advertisements and Soviet-inspired depictions of farmers toiling in the field. In the 1920s a revival of woodblock printing was fueled by a desire to communicate social values, Hearn said.

The exhibition also features a variety of contemporary prints, featuring scenes of modern life in China.

Despite printmaking's long history, the contemporary art market has failed to discover the form, Hearn said. But he is optimistic that Chinese artists will revive it.

Von Spee agreed. "I think that in the long run, we will rediscover printing as an artistic medium."

kdawson@chinadailyusa.com

Relief reaches isolated village

Relief reaches isolated village

Rainfall poses new threats to quake-hit region

Rainfall poses new threats to quake-hit region

Funerals begin for Boston bombing victims

Funerals begin for Boston bombing victims

Quake takeaway from China's Air Force

Quake takeaway from China's Air Force

Obama celebrates young inventors at science fair

Obama celebrates young inventors at science fair

Earth Day marked around the world

Earth Day marked around the world

Volunteer team helping students find sense of normalcy

Volunteer team helping students find sense of normalcy

Ethnic groups quick to join rescue efforts

Ethnic groups quick to join rescue efforts

Most Viewed

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|

Today's Top News

Health new priority for quake zone

Xi meets US top military officer

Japan's boats driven out of Diaoyu

China mulls online shopping legislation

Bird flu death toll rises to 22

Putin appoints new ambassador to China

Japanese ships blocked from Diaoyu Islands

Inspired by Guan, more Chinese pick up golf

US Weekly

|

|