Children crossing the cultural divide

Updated: 2012-08-28 08:01

By Yang Wanli (China Daily)

|

||||||||

|

Above: Christian Norris (left) at an emotionally charged reunion with his family in Beijing on Aug 29, 2009. He was relieved to know that he had been separated from his parents accidentally and not abandoned. Below: Christian, then named Dang Ziyang, with Julia Norris in 2001. Wang Xiaoxi / for China Daily |

|

Provided to China Daily |

Chinese youngsters who have been lost or abandoned by their families are often adopted by foreign nationals, but while that can provide many benefits, it can also prove traumatic and lead to psychological problems, reports Yang Wanli.

Christian, who has just finished his freshman year in college, is taking a gap year. He plans to travel to 11 countries in 11 months to help the poor, the sick, the elderly and - he hopes - orphans.

His desire to help others stems from his own traumatic childhood. Separated from his family at an early age and adopted by a woman from the US, the boy suffered an agonizing identity crisis.

In 2000, Julia Norris, who was working for an international Christian adoption agency, American World Adoption, visited Luoyang Orphanage in Henan province. While taking children on a trip to the local zoo, she formed an attachment with one of them, a 6-year-old boy called Dang Ziyang, and decided she wanted to adopt him.

When he was aged 5, the boy was lost when his father took him for a trip in a county city in the Ningxia Hui autonomous region. His father got off for a few minutes to buy food at a market. When he returned, the bus had already driven off, taking the child with it. Efforts to find him proved unsuccessful and eventually the child was handed over to the orphanage.

"I was 32 years old and unmarried, but I was ready to be a mother and I had the means to raise a child," said Norris.

At the time, China was one of the few countries willing to allow single women to adopt. Given her circumstances, it would have been very difficult for Norris to adopt a child in her home country.

The adoption process was relatively quick and just a year after she submitted her application to the China Center of Adoption Affairs, Norris was able to take her new son to the US.

Almost 40,000 Chinese children were adopted by foreign nationals between 1992 to 2009. In 2005, more than half of the children were relocated overseas, with 7,903 going to the United States. More than 80 percent of those children were girls.

However, Christian, as the boy was renamed, had problems adapting to his new home.

He felt like an alien in the strange land. "The people around me mostly had white skin and blue eyes and they spoke a language I couldn't understand," he said

He kept asking his new mom, "Where are my parents?"

Questions about his identity tormented Christian and he was eventually diagnosed as suffering from a form of post-traumatic stress disorder. "It was probably the hardest time of my life to see my son hurting so badly," admitted Norris.

Traumatized

In order to help Christian feel at ease in his new home, Norris decorated his room in a Chinese style, but sometimes the boy simply refused to step through the door. "When he was first adopted, he avoided any contact with China and refused to even remember his life there. He had been so traumatized by the experience of being separated from his birth parents that he wanted to shut out anything that reminded him of that," said Norris.

But even though he seemed to have settled and become a regular US boy, speaking fluent English and playing for the ice hockey team at his high school, Christian was unable to erase the memories of his early childhood. One day he told Norris, "I want to find my birth parents."

"I thought they had abandoned me, and that didn't feel good," he said. Eventually, Norris decided to pursue the boy's biological parents because she was worried that he would be tormented for life by the nagging questions. "He had the right to know about his past. I am his mother, and I should help him," she said. "He needed the peace of mind of knowing what happened."

Unlike most adoptees, who are given away as very young babies, Christian left China aged 7 and was able to recall many details of life in his home village. Those memories were of immense help when he set about tracing his birth parents.

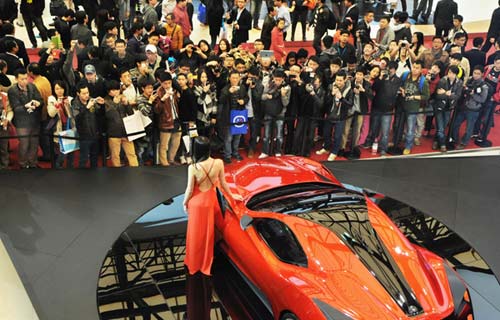

In August 2009, with the help of a Chinese non-governmental organization and clues provided by local residents, Christian was successfully reunited with his parents at a hotel in Beijing. His father fell to his knees and wept silently when he saw the son who had been lost for more than a decade. Christian's mother quietly buried her face in her hands. The young man stood upright, motionless and silent. He had forgotten how to speak Chinese.

The family marveled at the strapping teenager he had become: A handsome, athletic boy of 5 feet 8 inches, he towered over his Chinese relatives. "He's so big and he has hairy legs just like an American," said his uncle, quoted by a US journalist present at the meeting.

"He was excited, but very nervous on the day of the reunion. He did not show much emotion at first, probably because of all the media present, but when we visited the village where he had lived in Ningxia a few days later, the emotional impact of it all surfaced," said Norris. However, Christian later chose to return to the US.

"He never expressed an interest in staying in China," said Norris. "But, I think he would like to come back and maybe take Chinese language classes at a university some day."

The two families have kept in touch by phone, e-mail and letters during the past three years. Norris and Christian are planning to visit the boy's birth parents again next year. She said there is no doubt that his family in China loves him and misses him greatly.

Identity crisis

Culture shock is often seen among overseas-adopted children, according to Zhang Zhiwei, a lawyer who helps adopted kids find their birth parents, and also works to reunite kidnapped children with their families.

"Children older than 3 have a lot of memories about their past life, which heightens the cultural conflict. Sometimes, it leads to psychological problems that can hurt both the child and their adopted family," he said.

More than 80 percent of Chinese children who are adopted and taken overseas are unwanted girls. The others are usually those with special needs, who few Chinese people want to adopt. According to the CCAA, people in 17 countries are permitted to adopt Chinese children.

In China, adoptions have been declining since 2005 because the waiting list for a healthy child has grown longer and longer. Currently, people have to wait six years to adopt a healthy child, according to Joshua Zhong, co-founder of Chinese Children Adoption International, an agency that helps families to adopt.

Zhong has a special interest in these kids. He and his wife adopted a Chinese girl called Anna, who has a heart condition called tetralogy of fallot - often known as "blue baby syndrome". Having been abandoned at the age of four months, Anna, now 17, wants to know why she was rejected at such an early age and sometimes makes up stories to comfort herself.

Zhong said that Anna has sometimes mentioned that she would like to search for her biological parents. "We really hope we can figure out a way to help her. Like all adopted children, she deserves to know the truth," he said, adding that he has considered asking for information through newspapers or TV in Beijing.

Almost 85 percent of the adoptions in which his organization participates involve children with special needs, he said.

He said one of the reasons that some orphanages - especially those whose directors have visited adopted children living overseas - are more willing to place their children with foreigners is that they believe the kids will have better access to healthcare, education and community support.

Moreover, the Chinese domestic adoption system still needs to develop because it lags behind countries such as the US and Canada.

Family fortunes

Although orphanages provide homes for kids, children should grow up in a family environment, in an atmosphere of happiness, love and understanding, to ensure the full and harmonious development of their personalities, according to the Hague Adoption Convention on the Protection of Children and Cooperation in Respect of Intercountry Adoptions.

In light of the psychological problems that afflict some adopted children, the convention seeks to ensure that international adoptions are made in the child's best interests and to prevent the abduction, sale, or trafficking of children. Moreover, it has suggested that children are better off if they remain in their country of birth.

That view is often echoed by those who work in the field, but some experts believe that a childhood spent in normal family conditions provides the best opportunities for adopted children.

"Growing up in a family offers adopted children the chance of a healthy, normal life," said Deng Zhixin, a volunteer with Angelmon, a charitable foundation affiliated to the Chinese Red Cross Foundation. "We've found that children who have grown up in orphanages have poor working abilities and social skills. They're used to things being given to them and often find it hard to make a living once they go outside."

Contact the reporter at yangwanli@chinadaily.com.cn

(China Daily 08/28/2012 page6)

Relief reaches isolated village

Relief reaches isolated village

Rainfall poses new threats to quake-hit region

Rainfall poses new threats to quake-hit region

Funerals begin for Boston bombing victims

Funerals begin for Boston bombing victims

Quake takeaway from China's Air Force

Quake takeaway from China's Air Force

Obama celebrates young inventors at science fair

Obama celebrates young inventors at science fair

Earth Day marked around the world

Earth Day marked around the world

Volunteer team helping students find sense of normalcy

Volunteer team helping students find sense of normalcy

Ethnic groups quick to join rescue efforts

Ethnic groups quick to join rescue efforts

Most Viewed

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|

Today's Top News

Health new priority for quake zone

Xi meets US top military officer

Japan's boats driven out of Diaoyu

China mulls online shopping legislation

Bird flu death toll rises to 22

Putin appoints new ambassador to China

Japanese ships blocked from Diaoyu Islands

Inspired by Guan, more Chinese pick up golf

US Weekly

|

|