From garbage to garments

Updated: 2012-09-03 08:25

By Tiffany Tan (China Daily)

|

||||||||

|

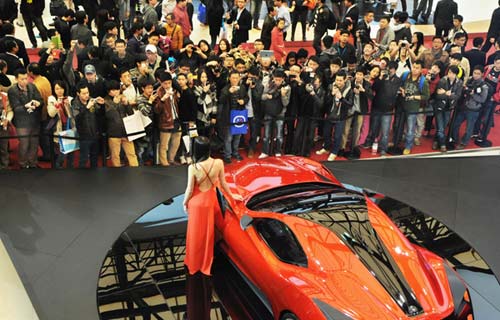

A model wears a design by Fake Natoo, a fashion label that uses materials destined for the dump. Provided to China Daily |

Clothes you no longer want, you might give to charity. But what happens to those that even charity groups can't use? Some end up with designers like Zhang Na.

Zhang, 32, uses discarded clothing to make a third of the garments for her label, Fake Natoo. More secondhand materials come from friends, even strangers, who've heard of her work upcycling - that is, creating greater value from objects destined for the dump.

Her reincarnated apparel, which debuted last summer, include a double-breasted fall coat made from seven pieces of cloth, as well as a long pencil skirt made of dozens of denim patches.

The project, which Zhang has named the Reclothing Bank, is her response to the rapid pace of development in China, where sentimental-value-laden old things are often quickly discarded for the latest products.

"Old clothes hold traces of people's lives, of humanity," Zhang, a Beijing native, says in a phone interview from her home in Shanghai.

"I hope that wearing redesigned old clothes can make people pause and contemplate their present and future.

"Everybody knows this is a really eco-friendly thing to do, but whether it's ultimately a sustainable undertaking is something we're still trying to understand."

She points out that a lot of time, energy and money go into washing, disinfecting and cutting up secondhand clothes for redesign.

Nathan Zhang, meanwhile, got into the upcycling business to help generate jobs for migrant women in Beijing.

Last year, he began supplying their cooperatives with garments that thrift shops couldn't sell. The women cut these up into patches that designers have turned into bags and new clothes.

Some of the merchandise ends up back at his Brandnu shop on Beijing's Wudaoying Hutong. From the sale of items they help produce, such as satchel bags made from colorful patches of knitwear, the migrant women's cooperatives get 10 percent of the profit.

"I didn't even know there was such a word as 'upcycling'," says Zhang, 40, a Canadian who hails from Beijing.

"I met a fashion design professor from Raffles (Design Institute Beijing), who told me, 'You're making upcycled fashion'. And I realized then that I was doing something very popular and that my project even went beyond upcycling by helping migrant women."

People have been upcycling throughout history to save on money or raw materials. But at the turn of the new millennium, it gained traction among designers, especially in the West, as a response to the call for a more sustainable lifestyle.

One of the world's pioneers and most recognized names in upcycled fashion is Orsola de Castro, a London-based Italian designer who founded the label From Somewhere in 1997.

"In those days in London, there were many designers using vintage as part of their collections, so we kind of followed that," De Castro, 46, says in a phone interview.

"Once I realized quite how much surplus and waste the industry - particularly the high-end designer industry - was generating, then I became more of an advocate."

She has since helped major international labels like swimwear maker Speedo and Topshop, a British high-street retailer, convert their unsold stocks, surplus pieces or fabric waste into upcycled collections.

In China, upcycled fashion is a much newer and more exotic concept.

Redress, an NGO that promotes sustainability in the Chinese fashion industry, for instance, has only a dozen names on its database of mainland and Hong Kong fashion designers involved in upcycling.

More mainland designers seem to be motivated by the desire to preserve a piece of history or culture, rather than the environment.

"Some people are buying clothes 10-20 years old and reselling them after they've been redesigned to offer a sort of historical collection that showcases other types of fashion," Wang Jiajun, an analyst at the China Market Research Group in Shanghai, says.

"Green or environmentally friendly clothing is far less popular than vintage clothes. It usually appears only in exhibitions and fashion shows."

Chinese garment factories, the world's biggest producers, last year churned out 25.42 billion pieces of clothing, two-thirds of which were sold overseas, according to data from business media company Global Sources.

These factories generate at least 1 million tons of textile waste a year, says Gong Yan, an associate professor at the Beijing Institute of Fashion Technology, who specializes in garment materials.

There is no data for exactly how much of this waste is reused or recycled by the garment industry, says Gong, who's also a member of the All-China Environment Federation's research committee on environmental protection standards.

But one thing is clear: Reusing or recycling is far more environmentally friendly than discarding existing materials and starting from scratch.

"If old clothes are destined for the landfill, incineration or disposal, then washing and reusing these would be much better," Steven Gillespie, director of the University of Glasgow's applied carbon management program, says in an e-mail.

"Old clothes have a lot of embedded energy: the energy used to grow the cotton, creating the fabric, sewing the pieces together, electricity use, packaging the goods, transporting the goods and so forth. Therefore, if one were to avoid the creation of new material from using already created fabric, then this has a positive environmental impact."

Whatever their reasons for upcycling, and whether they know it or not, Chinese designers and entrepreneurs like Zhang Na and Nathan Zhang are contributing to this impact by keeping old clothes alive.

tiffany@chinadaily.com.cn

(China Daily 09/01/2012 page11)

Relief reaches isolated village

Relief reaches isolated village

Rainfall poses new threats to quake-hit region

Rainfall poses new threats to quake-hit region

Funerals begin for Boston bombing victims

Funerals begin for Boston bombing victims

Quake takeaway from China's Air Force

Quake takeaway from China's Air Force

Obama celebrates young inventors at science fair

Obama celebrates young inventors at science fair

Earth Day marked around the world

Earth Day marked around the world

Volunteer team helping students find sense of normalcy

Volunteer team helping students find sense of normalcy

Ethnic groups quick to join rescue efforts

Ethnic groups quick to join rescue efforts

Most Viewed

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|

Today's Top News

Health new priority for quake zone

Xi meets US top military officer

Japan's boats driven out of Diaoyu

China mulls online shopping legislation

Bird flu death toll rises to 22

Putin appoints new ambassador to China

Japanese ships blocked from Diaoyu Islands

Inspired by Guan, more Chinese pick up golf

US Weekly

|

|