No match for progress

Updated: 2012-11-19 08:08

By Wang Ru (China Daily)

|

||||||||

|

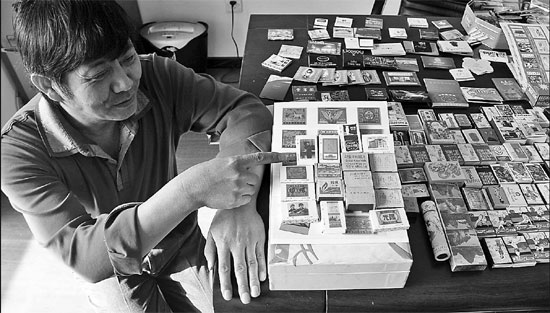

Beijing collector Wang Yuxiang and his matchbox collection. Photos by Wang Ru / China Daily |

Cigarette lighters and other conveniences have killed a once-essential commodity, but matchbox-label collectors are keeping the flame of a lost art alive, Wang Ru reports.

As time goes by, some things fade into history while other things pop up and thrive.

After the license-plate lottery began for private vehicles in Beijing, Wang Yuxiang's family-owned car-rental business boomed almost overnight.

But change hasn't always been kind to the Being native, 55, a passionate collector of matchbox labels. Wang heard some bad news in September.

Botou Match Co Ltd, the biggest producer of matches in Asia - 280 km away from Beijing in neighboring Hebei province - announced its bankruptcy.

"It is inevitable in times when few people use matches," says Wang, sitting in his office in Dongcheng district in Beijing.

"There are many fire-making tools now. The value of the match has gone," says Wang, who similarly notes that he seldom writes with a pen instead using a computer.

In the 1990s, there were about 40 match factories across China. According to Wang, only three are still producing matches now.

The existing match factories, like the oldest one in Beijing, now only produce orders from wedding planning companies and hotels. Some so-called match companies are in fact souvenir producers.

However, the story of the match has not been extinguished. Earlier this year, a nationwide convention of matchbox-label collectors, known as phillumenists, was held in Nanjing, Jiangsu province.

"The labels of matchboxes are full of information and aesthetic value, like stamps. I am glad to be one of the collectors who have recorded the stories of matches in China," Wang says.

Since the 1970s, when Wang saved his first matchbox label, he has been charmed by the colorful patterns that often represent diverse cultures, landscapes and characteristics of different regions.

Matches then were a necessity of life, when most people used them to smoke and to light coal stoves.

In the planned-economy era, a box of matches remained at the price of 2 fen or 0.02 yuan, affordable for daily use. "It was very common that some customers and neighbors came to borrow matches for lighting cigarettes or making their lunches," he says.

One year in 1970s, Wang's remembers, an official proposal to raise the price of a box of matches from 0.02 yuan to 0.03 stirred a wide debate.

A national newspaper published the proposal and discussion. The price was never raised.

The match industry witnessed the modern history of China. In the old days, matches were sometimes called yang huo, literally meaning "foreign fire".

The first box of matches to reach the country was a foreign envoy's gift to Emperor Jiaqing (1760-1820). Later in the Qing Dynasty (1644-1911), the match industry was brought to China by colonists mainly from Britain and Japan, who controlled the profitable business.

But matches were still a luxury, not a product for everyone, until industry took root in China.

In 1879, the country's first match factory was established by a Chinese businessman returning from Japan in Foshan, Guangdong province.

In 1906, the first match factory in Beijing was founded after Emperor Guangxu (1871-1908) accepted a proposal from a businessman named Wen Zuyun to "protect the national interest and booming industry". In 1953, it became the Beijing Match Factory.

In 1912, the Botou Match Factory was founded in Botou city in Hebei. After the founding of New China in 1949, it became the country's major match producer. The period of yang huo was gone and Chinese people had cheap matches in their lives.

In the golden years of the industry, there were over 130 match factories all over the country. Some big factories hired artists and painters to design the labels on matchboxes. In 1959, the China Academy of Fine Arts designed a set of 36 matchbox labels themed with Beijing landscapes, flowers and birds to celebrate the 10th anniversary of the founding of New China.

Since 1988, mass production of lighters, heating systems and gas cookers has improved the quality of Chinese people's lives, but those implements snuffed out the need for matches. In 1992, Beijing Match Factory shut down and was relocated to a suburban area.

Zhou Xiaofang, a co-owner of Zhenquan, the only shop in Beijing that sells matchbox labels and hosts a salon for collectors every two months, bought a whole room of matchbox labels at a low price, sold by the factory in 1992.

"I didn't realize there were people collecting the labels. I was just amazed by the beautiful patterns," Zhou says.

Many match factories in China closed then, leaving the market to Botou Match Factory, which enjoyed some lucrative years before its bankruptcy.

Han Qingsheng, the manager of Zhenquan, visited the factory with collectors and government officials in 2000.

"The factory produced at full steam day and night. The director still welcomed us and treated us in a good restaurant," Han recalls.

After a series of mergers with small factories, Botou Match Factory became the largest match producer in Asia, with its daily production capability reaching 7 million boxes per day, or 700 million matchsticks.

"A package of 1,000 boxes sold for only 26 yuan. Many local people made their living by sticking labels on matchboxes," Han says.

However, in 2004, when Han wanted to revisit the factory, he had to make an appointment. The factory didn't open every day due to its rapidly declining orders.

"In fact, a match is safer than a lighter and still useful in the remote countryside," Han says.

Despite changing times, Han says, "the culture of matchbox labels is preserved by museums and individual collectors like Wang". Zhou and Han still organize shows and holds label design competitions in primary schools.

Jia Chongzheng, 70, former deputy director of the Beijing Match Factory who started to work there in 1965, misses the golden days.

He retired in 1998 and lives frugally in an old residential building within the old factory zone. He feels regret for the downfall of the industry, but he sees an upside, too.

"Matches are inconvenient and consume a lot of wood. You have to face the progress of time and society," he says.

"The end of the match industry reflects the development of the country. I am happy to see it."

|

Matchboxes were once an indispensable part of daily life. |

(China Daily 11/19/2012 page20)

Relief reaches isolated village

Relief reaches isolated village

Rainfall poses new threats to quake-hit region

Rainfall poses new threats to quake-hit region

Funerals begin for Boston bombing victims

Funerals begin for Boston bombing victims

Quake takeaway from China's Air Force

Quake takeaway from China's Air Force

Obama celebrates young inventors at science fair

Obama celebrates young inventors at science fair

Earth Day marked around the world

Earth Day marked around the world

Volunteer team helping students find sense of normalcy

Volunteer team helping students find sense of normalcy

Ethnic groups quick to join rescue efforts

Ethnic groups quick to join rescue efforts

Most Viewed

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|

Today's Top News

Health new priority for quake zone

Xi meets US top military officer

Japan's boats driven out of Diaoyu

China mulls online shopping legislation

Bird flu death toll rises to 22

Putin appoints new ambassador to China

Japanese ships blocked from Diaoyu Islands

Inspired by Guan, more Chinese pick up golf

US Weekly

|

|